A pulmonary cavity is defined as a gas-filled space within a zone of pulmonary consolidation or within a mass or nodule, often seen as a lucency or low-attenuation area.1 Cavities are present in a wide variety of processes, such as lung cancer, autoimmune diseases, infections, congenital malformations and trauma. A chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) are the radiographic means most often used to assist diagnosis.1,2

Traumatic pulmonary pseudocysts (TPP) are uncommon cavitary lesions developed as consequence of blunt thoracic trauma. They are more frequent in children and young adults.3,4

A 16-year-old female, equestrian practitioner went to the emergency room because of right chest trauma caused by two horse kicks. She denied any symptoms other than pain. Physical examination showed two bruises and severe pain on palpation of right costal grid and sternum, without other changes.

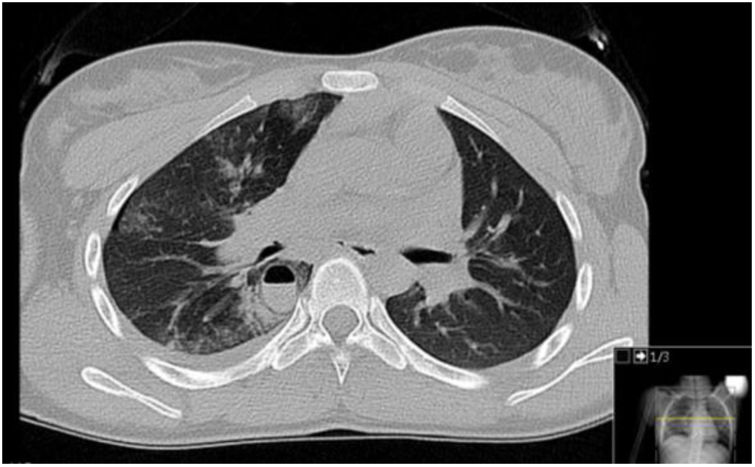

Chest and ribs X-rays were normal. Thoracic CT performed on the same day as the horse kicks, demonstrated two cavities, one in the lower lobe of the right lung with air-fluid level and 70mm diameter (Fig. 1) and other in the medial segment of the middle lobe with 15mm diameter, without broken ribs.

White blood cell count revealed leucocytosis (18.200cells/μL) with neutrophilia (15.900cells/μL). Mantoux test, Mycoplasma and HIV serology were negative; immunoglobulin A, G and M and complement C3 and C4 were normal; blood culture and aerobic, anaerobic and fungal cultures of bronchoalveolar lavage were negative.

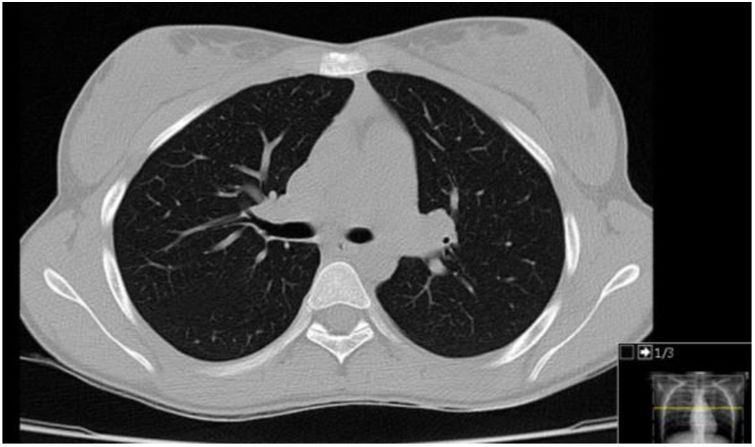

She completed empirical treatment with ampicillin and clindamycin for 10 days. Thoracic pain improved gradually and she remained asymptomatic and was discharged to adolescent consultation. Follow-up CT performed 3 months after the episode demonstrated a complete resolution of the pulmonary changes seen in the previous study (Fig. 2).

TPP is an uncommon cavitary lesion lacking an epithelial lining or bronchial wall elements, which develops within the pulmonary parenchyma after blunt chest trauma. Such pseudocysts can occur at any age but they are most frequent (80–85%) in children and young adults.3,4

The mechanism by which this injury occurs is not known exactly, but it is believed that younger people have a more elastic and pliable chest wall, which permits greater transmission of kinetic energy to the intrathoracic structures such as pulmonary parenchyma.3–5 The rapid compression and decompression lacerates alveoli and interstitium. Retraction of the elastic tissue of the lung results in small cavities filled with air and/or fluid. Cavities tends to grow until the pressure of the adjacent parenchyma equals the intracavitary pressure.3–6 Another proposed mechanism is that the closure of the glottis or bronchial obstruction, at the moment of trauma, makes it difficult for the air to escape in the compressed segment and the lacerated parenchyma forms a cavity.4,6

Most TTP appear in the first 12h after the trauma. However, they can occur immediately or within a few days of the injury.3,6 The patient may be asymptomatic or manifest subtle or nonspecifc symptoms such as cough, chest pain, hemoptysis and dyspnea. Occasionally, they also present with mild fever and leucocytosis.4,6,7

TTP can be detected on chest X-ray, but CT is better for identification.4,6 Their sizes range from 2 to 14cm in diameter and they can be spherical or oval, single or multiple, unilateral or bilateral. They may be observed on the site of injury or on the other side and the majority are found in lower lobes.3–6

The differential diagnosis is extensive and includes infections such as tuberculosis, mycosis, lung abscess and pneumatocele, autoimmune diseases, lung cancer, bronchogenic cysts and adenomatoid cystic malformation. The history of chest trauma and the presence of a contusion at the site of the impact usually help the diagnosis, but if the cavitary lesion does not decrease with time, other etiology must be considered.5,6

TPP are benign lesions and the treatment is generally conservative. Spontaneous resolution usually occurs within 6 weeks after the trauma in adults and 3–4 months in children.5,6 The use of empirical antibiotic therapy should not be a routine and is only warranted by persistent fever, leucocytosis, radiographic modifications, or other signs of infection.4,7

In conclusion, the differential diagnosis of pulmonary cavities includes a wide variety of diseases. The authors emphasize the importance of considering pulmonary pseudocysts when cavities appear in the context of a high energy trauma in patients without comorbidities, and no prior systemic symptoms. In this case, the temporal relationship with chest trauma and the fact that the whole study was normal corroborated the diagnosis of traumatic pulmonary pseudo cysts, a rare condition found in less than 3% of cases.4,7

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.