More than a century of research has increased our understanding of the complex immunological pathways underlying asthma airway inflammation.1 The resulting pharmacological advances and the development of monoclonal antibodies have allowed some patients, even those with the most severe form of the disease, to see their symptoms disappear completely.2

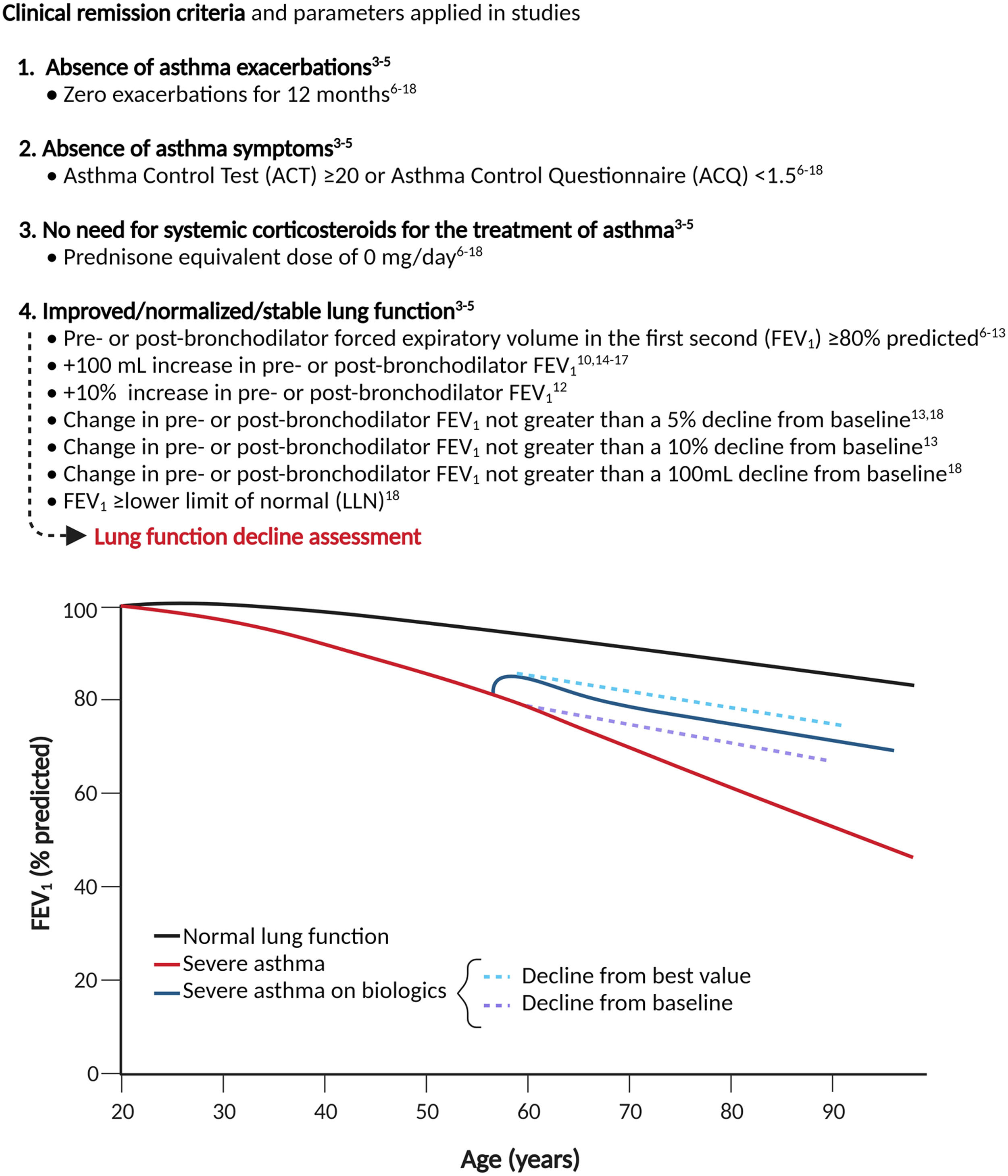

The concept of “remission”, which is already established in fields like rheumatology and oncology, has been embraced as an ambitious but achievable therapeutic goal.3 While there is no universally accepted definition of remission yet, several groups of experts3–5 have recently agreed that the remission should be based on a set of clinically relevant composite outcomes (Fig. 1). A fair degree of consensus has been reached about the first three criteria and a specific guide for evaluating treatment response provided; however, this is not the case for the assessment of lung function. Indeed, following a comprehensive literature search, we found that seven definitions have been proposed, but none has achieved wide agreement (Fig. 1).6–18

This heterogeneity resulted in a lack of consistency within the studies that examined remission attainability, producing results which were hardly comparable as the percentage of patients meeting the criteria ranged from 18.3 %18 to 43.7 %,17 thus hindering the research of response predictors. A possible solution might be to exclude lung function from the definition of remission due to its intrinsic volatility, influenced by various confounding factors, such as ethnicity, age, gender, smoking status, BMI and the use of bronchodilators. Nevertheless, the concepts of normalizing and/or stabilizing respiratory function should be considered. Some patients, especially those with a long history of disease, may meet the first three conditions but fail to improve the forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) due to altered airway architecture secondary to remodeling phenomena.19 Nonetheless, it has been shown that anti-IL-5 therapies can mitigate the lung function decline in severe eosinophilic asthma patients.20 In this context, a desirable outcome would be to prove that the loss of respiratory function aligns with, or significantly approaches, those of healthy subjects (median −22.4 mL/year in FEV1 [range 17.7 to 46.4 mL/year], accelerating for each decade of age).21 Such functional parameters would support a true disease modification and could potentially serve as a surrogate marker of clinical and biological remission. However, this would require a relatively long-term assessment at different time points since two measurements only may not adequately estimate the rate of lung function decline, and the initial improvement in lung function due to biological therapies tend to gradually decrease after 12 months eventually returning to baseline values in some cases22,23; therefore a 24-month lung function monitoring would be desirable. Indeed, if prevention of lung function deterioration was applied in REDES post hoc, after 1 year of anti-IL-5 treatment, 63 % of patients would qualify as having no worsening from baseline in post-bronchodilator FEV1, a percentage that is likely to be inflated by the relatively short observation period.9

Recently, several insightful criteria for lung function “stabilization” have been introduced, namely a change in FEV1 not greater than a 5 % or 10 % or 100 mL decline from baseline or a FEV1 greater or equal to the lower limit of normal (LLN).13,18 However, we believe that “stabilization” should be defined with respect to the best value obtained during the first 12 months of therapy rather than compared to baseline since the former would provide a more accurate snapshot of on-treatment decline. More prospective studies assessing pulmonary function decline during biologics are needed, with the challenging ultimate goal of developing specific decline charts, starting from the personal best FEV1 % achieved after 2 years of therapy, and then followed at least yearly for 5–10 years. In conclusion, how should lung function be assessed within the definition of asthma remission? Since a broad consensus has yet to be reached and studies assessing long-term lung function decline during biologics are lacking, we suggest performing sensitivity analysis using both FEV1 % ≥80 % and +100 mL increase, which are the most commonly used parameters (Fig. 1) to ensure adequate reproducibility. Furthermore, we strongly advise that future studies should include lung function decline, preferably for at least 24 months, using the personal best value obtained during the first 12 months of treatment as a reference. The ultimate goal should be to provide physicians with a homogeneous and consistent definition that can bridge the gap between clinical and biological remission to enhance accurate outcome prediction and, consequently, focused treatment prescription.

CRediT authorship contribution statementS. Nolasco: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. R. Campisi: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. N. Crimi: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. C. Crimi: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Visualization.

This study was not funded.