In coronavirus disease (COVID-19), physical capacity is one of the most impaired sequelae. Due to their simplicity and low cost, field tests such as the six-minute walk test (6MWT) are widely used However, in many places it is difficult to perform them and alternatives can be used such as the 1 min sit-to-stand test (1min-STST) or the Chester step test (CST). Therefore, our objective was to compare the 6MWT, 1min-STST and the CST in post-COVID-19 patients.

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional analysis in post-COVID-19 patients, compared with matched controls (CG). Demographic characteristics and comorbidities were collected. We analysed oxygen saturation (SpO2), heart rate (HR), and the modified Borg scale in the 6MWT, 1min-STST, and CST. Additionally, the correlations between tests were analysed.

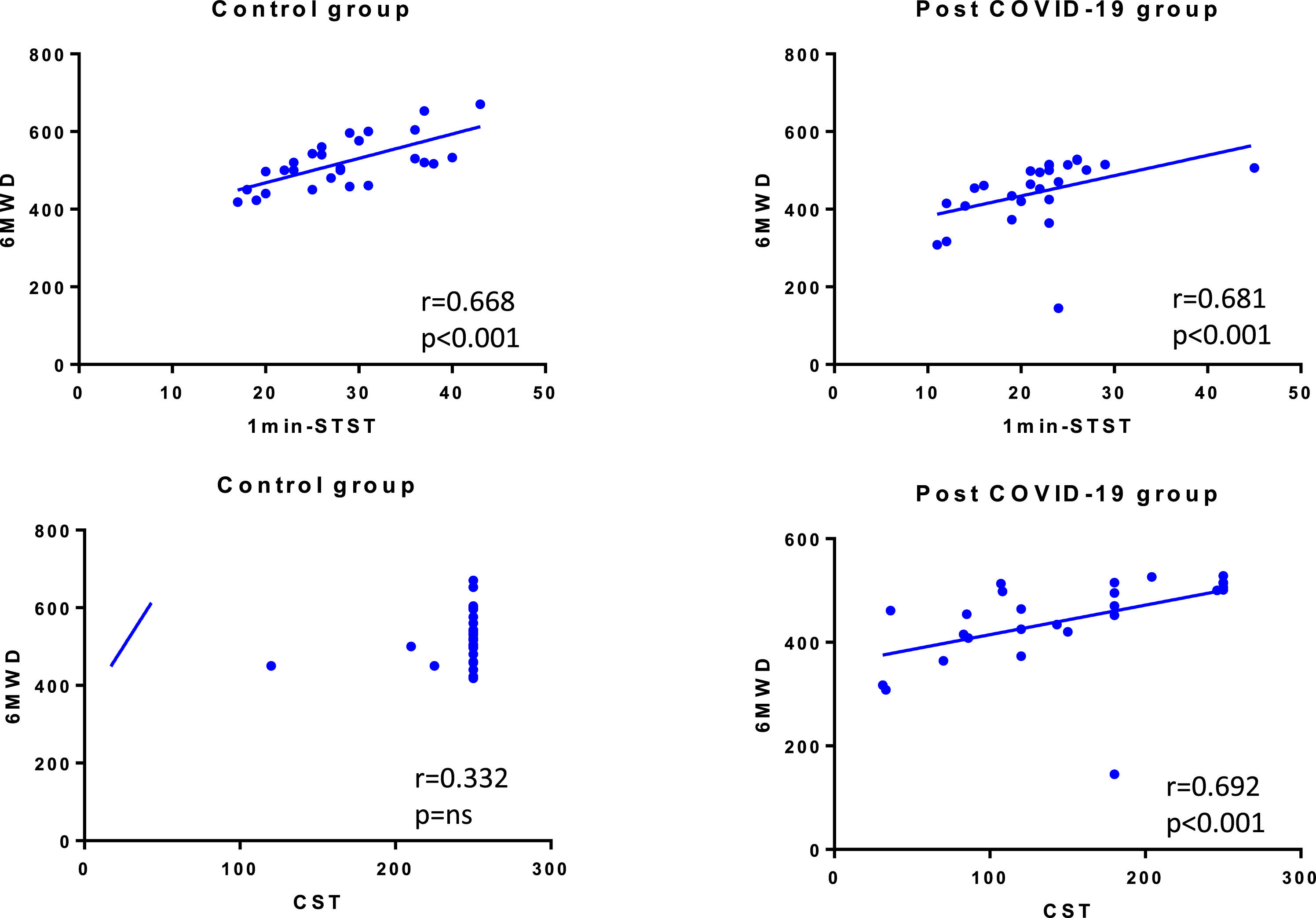

ResultsWe recruited 27 post-COVID-19 patients and 27 matched controls. The median age was 48 (IQR 43-59) years old (44% female). The median distance walked in 6MWT was 461 (IQR 415-506) m in post-COVID-patients and 517 (IQR 461-560) m in CG (p = 0.001). In 1min-STST, the repetitions were 21.9 ± 6.7 and 28.3 ± 7.1 in the post-COVID-19 group and CG, respectively (p = 0.001). In the CST, the post-COVID-19 group performed 150 (86-204) steps vs the CG with 250 (250-250) steps (p < 0.001). We found correlations between the 6MWT with the 1min-STST in COVID-19 patients (r = 0.681, p < 0.001) and CG (r = 0.668, p < 0.001), and between the 6MWT and the CST in COVID-19 patients (r = 0.692, p < 0.001).

ConclusionThe 1min-STST and the CST correlated significantly with the 6MWT in patients post-COVID-19 being alternatives if the 6MWT cannot be performed.

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has been a challenge for health systems, affecting more than 500 million people, with more than 6 million deaths as of June 2022.1 Although the vast majority of people infected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus develop mild or asymptomatic disease, about 20% develop severe disease requiring hospitalisation, and about 6% require critical care in an intensive care unit.2

Albeit the disease is primarily respiratory, it affects multiple systems such as cardiovascular or neurological, leaving a broad spectrum of sequelae that affect COVID-19 survivors in the short, medium and long term.3–6 Among the most commonly reported sequelae are fatigue, dyspnoea, headache and impairment of physical capacity.4,7 Undoubtedly, the appearance of sequelae affects the quality of life and the return to work in the active population.4

Due to the sequelae, the different health systems have had to generate follow-up programmes that focus primarily on imaging, lung function, symptoms, and physical capacity.8,9 One of the pillars of the follow-up is the evaluation of physical capacity, which can be assessed with laboratory tests or field tests, such as the six-minute walk test (6MWT), the 1 min sit-to-stand test (1min-STST) or the Chester step test (CST).10–14

These tests can be performed in low-resource contexts and have widely demonstrated their usefulness in evaluating physical capacity in different respiratory, metabolic, cardiological or neurological diseases.10 However, to provide specific information, functional or exercise capacity, a test must be chosen according to the characteristics of each subject, the setting and the physiological expected answer. For example, the 6MWT is a widely used test; however, it has shown a low execution rate in some COVID-19 patients at hospital discharge.15 In addition, the execution of the 6MWT requires a 20-to-30-metre corridor that is often unavailable in hospitals or rehabilitation centres16 and even less so at home.

There are modifications of the 6MWT in the length of the corridor, the space limitations being the main reason for using a shorter than recommended walkway.17 A recent study compared the 10-metre and 30-metre circuits, finding that patients with chronic non-communicable diseases walk about 70 m less on the 10-metre circuit, which also exceeds the minimally clinically important difference.18 This effect may be exacerbated in patients with post-COVID-19 with prolonged bed rest and older age, which can affect balance and gait patterns and/or strategies.19

Field tests are widely used in intervention programmes such as rehabilitation, and because of that and the need to find simple, reliable and effective measures, it is essential to look at alternatives to the 6MWT to assess COVID-19 patients during the follow-up and rehabilitation.13,20,21 Therefore, our objective was to compare the 6MWT, 1min-STST and the CST in post-COVID-19 patients.

MethodsDesign and participantsWe conducted a cross-sectional analysis in patients recovering from COVID-19 pneumonia admitted to the follow-up programme in the Hospital Virgen de la Torre (Madrid, Spain) between March 2021 and May 2021. Ethics committee approval was obtained, and all patients signed the informed consent. This study follows the recommendations of the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology guidelines (STROBE).22

Inclusion criteria were as follows: patients older than 18 years, diagnostic of COVID-19 by positive PCR assay findings for nasal and pharyngeal swab specimens, patients with dyspnoea and/or persistent fatigue, with mild/moderate physical activity previous to infection, oxygen supply equal to or less than 4 litres per minute. Exclusion criteria were as follows: the presence of locomotor or cognitive impairment before the infection, refusal to participate, and any pre-existing condition such as orthopaedic or neurological comorbidities limiting the ability to perform the standard field test.

The control group participants, without infection by COVID-19, without symptoms such as fatigue or dyspnoea, with mild/moderate physical activity, were recruited by inviting medical staff and their relatives. These participants were matched to the treatment group based on gender and age.

Sample size calculationFor the sample size, we used the study of Karloh et al., which compared different field tests in COPD patients.20 Accepting an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of 0.2 in a two-sided test, 23 subjects are necessary for each group to recognise as statistically significant a difference greater than or equal to 1 unit. The expected standard deviation is assumed to be 1.1. A drop-out rate of 15% has been anticipated.

MeasurementsAt the time of admission, demographic characteristics, medical history, exposure history and underlying comorbidities were collected. The main outcome measures were physical capacity, assessed through 6MWT, 1min-STST, and CST. All tests were conducted in the same room, with only the presence of the researcher and the patient to avoid distractions. The order of application of each test was randomised. Adequate rest was provided between the tests, which allowedg SpO2 and heart rate to return to pre-exercise values with a minimum of 30 min between tests.

6MWT: The 6MWT was performed indoors, along a flat, straight, 30 m walking course, according to international guidelines.10 Subjects were instructed to walk the circuit from one end to the other covering as much distance as possible in the assigned six-minute period.10 We used the reference values based on the healthy adult population reported by Enright and Sherrill.23

1min-STST: The test was performed with a chair of standard height (46 cm) without armrests positioned against a wall. Participants were not allowed to use their hands/arms to push the seat of the chair or their body. Participants were instructed to complete as many sit-and-stand cycles as possible in 60 s at self-paced speed.24 We used the reference values based on the healthy adult population previously reported by Strassmann et al.24

Chester step test: The CST consists of going up and down a step up to 30 cm in height at a pace set by a signal sound, which progressively increases in speed up to five levels. We used a step of 16 cm. In the first minute, patients go up and down the step 15 times, increasing every two minutes. The maximum test time is 10 min.20

The modified Borg scale (0–10) measured dyspnoea and fatigue immediately before and after all tests.25 A finger oximeter was used to record oxygen saturation (SpO2) and heart rate (HR). A desaturation level of ≥4% was considered clinically significant.26 The evaluator had previous experience in this test. All tests were performed two times due to the learning effect described in some field tests.27

Statistical analysesThe SPSS software version 25.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all the statistical analyses. The Shapiro-Wilk normality test will be applied to the recorded data, and, depending on the nature of the variables, the corresponding parametric or non-parametric test will be applied. The t-test for independent samples or the Mann-Whitney U test will be used for pre-post comparisons. Mann-Whitney U test, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal-Wallis test with Tukey's post-hoc test will be used to compare HR, SpO2, dyspnoea and leg fatigue pre-post.

The variation in cardiorespiratory variables between test levels will be compared by means of a two-way ANOVA or the corresponding non-parametric test, with a test, with a post-hoc paired t-test or a Wilcoxon test. The association between the variables will be verified by means of Pearson's or Spearman's correlation coefficient. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was set at 5% (p < 0.05).

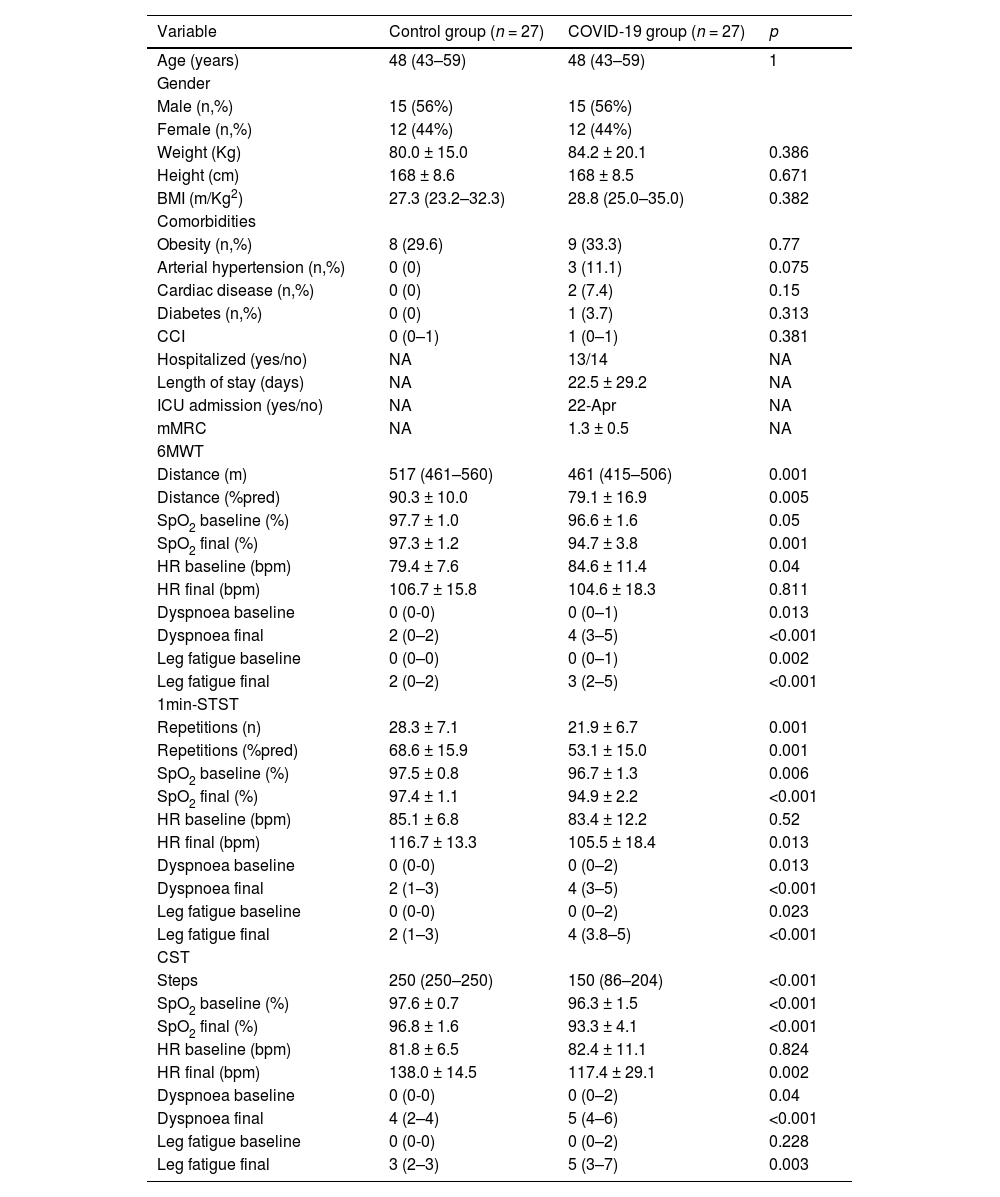

ResultsWe recruited 27 patients with COVID-19 diagnosis who were compared with 27 healthy matched controls. The median age was 48 (IQR 43–59) years (12 females, 44%). The mean time between hospitalisation and the field tests evaluation was 5.8 ± 0.5 months. The baseline patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Fourteen patients were hospitalised with a mean of 28.1 ± 34.0 days of the length of stay. Only four required ICU admission. The mean mMRC score was 1.35 ± 0.5.

Descriptive statistics of the included patients.

Abbreviations: BMI: Body mass index; CCI: Charlson comorbidities index; ICU: Intensive care unit; mMRC: Modified medical research council; 6MWT: Six-minute walk test; SpO2: Oxygen saturation; HR: Heart rate; bpm: beats per minute; 1min-STST: 1-minute sit-to-stand test; CST: Chester step test. Values are expressed as the mean ± SD if data are normally distributed or as the median (P25–P75) if data distribution is skewed.

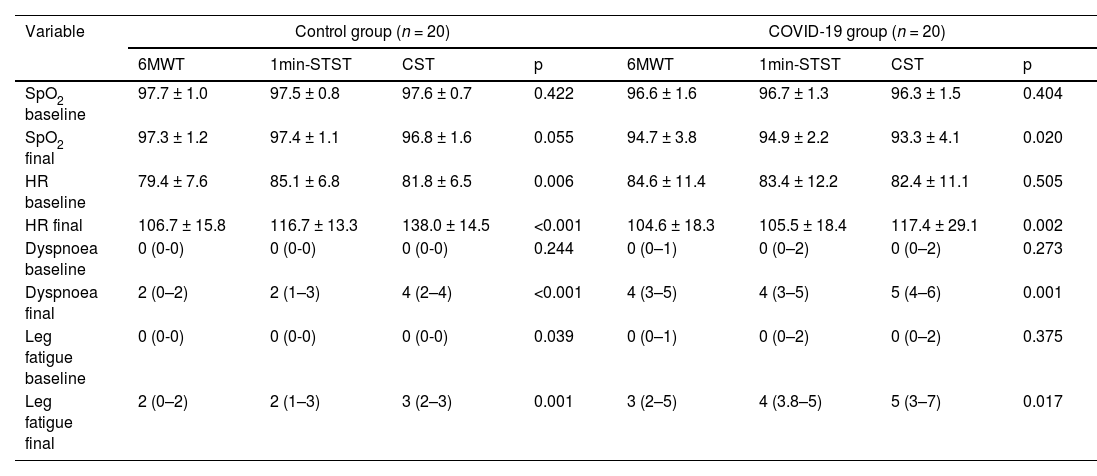

Regarding the physical capacity, the median distance walked in 6MWD was 461 m (IQR 415–506) in post-COVID-patients and 517 m (IQR 461–560) in the CG (p = 0.001). The final SpO2, HR baseline, final dyspnoea and final leg fatigue significantly differed between groups. For the 1min-STST, the number of repetitions was 21.9 ± 6.7 and 28.3 ± 7.1 in post-COVID-19 and control groups, respectively (p = 0.001). The SpO2 baseline, final SpO2, final HR, final dyspnoea and final leg fatigue differed significantly. Regarding the CST, we found differences between the number of steps; the COVID-19 group performed a median (IQR) of 150 (86–204) versus the control group with 250 (250–250). The SpO2 at baseline, final SpO2, final HR, final dyspnoea and final leg fatigue showed a significant difference. At the end of the 6MWT and 1min-STST, 22% of the patients showed exercise-induced desaturations (EID) (Table 2).

Comparison between exercise physiological response between different tests.

Abbreviations: 6MWT: Six-minute walk test; 1min-STST: 1-minute sit-to-stand test; CST: Chester step test; SpO2: Oxygen saturation; HR: Heart rate.

Finally, we also found correlations between 6MWT and 1min-STST in COVID-19 patients (r = 0.681, p < 0.001) and in control group (r = 0.668, p < 0.001), and between 6MWT and CST only in COVID-19 patients (r = 0.692, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

DiscussionThis research showed that the 1min-STST and the CST correlated significantly with the 6MWT in patients post-COVID-19.

The reference test to assess physical capacity in respiratory, cardiovascular or metabolic diseases is the 6MWT.10,28 However, the pandemic has shown us that it is not always easy to perform the 6MWT since it requires certain special conditions for its development, such as a 30 metres corridor (or at least 20 m).10 Our results show, referencingthe obtained data, that there is an important correlation between the CST and the 1min-STST with the 6MWT. This correlation is in line with similar studies but in different populations such as lung transplant candidates, interstitial lung diseases, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.20,29–31 Therefore, when there are limitations to performing the 6MWT in COVID-19 patients, the 1min-STST and CST could be alternatives.

We compared the physiological exercise response between the three tests in the COVID-19 group and the CG. For the CG, we did not observe significant differences in physiologicalvariables, although there was a tendency to increase perceived symptoms at the end of CST. A possible explanation of those results is because the CST is an incremental test that tries to achieve the maximal subject exercise capacity. Furthermore, step climbing is a heavy exercise that supposes a technical gesture, going up and down, that involves a much greater muscle mass and energy expenditure, by having to lift the whole body weight, than walking on a flat corridor as in the 6MWT or lifting the body weight from a chair.32

However, in COVID-19 patients, we found a significant increase in the symptoms at the end of CST, but not a parallel increase with similar magnitude on the HR. Probably it can be attributed to the fact that COVID-19 patients have a cardiorespiratory impairment that limits the maximal exercise capacity and forces patients to decrease performance.21,33

Regarding EID, our data showed that 22% of patients had EID. These results are similar to those found previously.34,35 Previous reports state that the low intensity and short duration of the STS might have underestimated the severity of exercise-induced desaturations as compared with standard exercise tests such as the 6-min walking test or cardiopulmonary exercise tests.34 Our data coincide with these findings given that both groups had the same number of desaturators, however EID during the 6MWT was greater than 6% in 5/6 patients (one even decreased 13%), whereas in the 1min-STST, only 1 of the 6 patients desaturated more than 5%.

Although the three tests achieved similar results, it is crucial to consider that a more significant lower extremities effort is required to execute the CST or the 1min-STST.20,24,36 This result was confirmed by the reported perception of lower extremity fatigue compared to 6MWT. Therefore, not doing these testst should be considered nwhen extreme lower extremity fatigue is reported before the assessments. Although in some patients the 6MWT can behave as a maximal test, it is considered a submaximal test, so our results should be analysed with caution since they are tests aimed at different objectives. On the other hand, the CST is an incremental maximum capacity test and should be used with caution in a remote setting, especially in patients with a probability of desaturation.

There are at least three different versions of the STST.36 We decided only to study the one-minute version, given that, in other pathologies, such as COPD, the literature has shown that 1min-STST has the best correlation with the 6MWT.37 Although the technical movement of the 5-STST or the 30 s STST is the same because the test expended time, the 1min-STST stress lower extremities significantly, but it does not employ the cardiorespiratory reserves in the same way.37 For this reason, these shorter exercise tests are typically used to predict falls in older adults or assess the strength of the lower extremities in those populations.38,39

Given the moderate correlation observed between both tests with the 6MWT, because of its simplicity, their use could be considered face-to-face or in remote evaluations.40,41 Furthermore, the literature has shown and recommended using the 1min-STST for rehabilitation and telerehabilitation programmes.13,36,42 This fact is a critical point in the current pandemic since many services have had to generate remote monitoring and rehabilitation programmes due to the operational problems of rehabilitation services.43 Our results show that 1min-STST and CST can be used as an alternative in remote programmes.

The present study has some limitations. The sample size is small; however, the calculated sample size was 23 subjects per group for a power of 80%. At the end of the study, the calculated power was 93%, so the sample size was sufficient. On the other hand, our study did not evaluate the oxygen consumption response. It requires sophisticated equipment and specialist professionals not commonly available in the clinical setting. However, our objective was to show field tests that can be carried out in different contexts, from primary care to the hospital. Additionally, our population was young, so they had few comorbidities and it was not possible to determine if this could have had an effect on the performance of the tests. Finally, it was not possible to blind the evaluator since she was the professional who worked in the pulmonary rehabilitation programme.

ConclusionThis research showed that the 1min-STST and the CST correlated significantly with the 6MWT in patients post-COVID-19. The 1min-STST and the CST can be an alternative to evaluate functional capacity when the 6MWT cannot be performed. Future studies should evaluate whether these field tests are sensitive to alterations such as rehabilitation or recovery from COVID-19 over the months.

FundingNo funding.

CRediT authorship contribution statementR. Peroy-Badal: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. A. Sevillano-Castaño: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. R. Torres-Castro: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. P. García-Fernández: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. J.L. Maté-Muñoz: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. C. Dumitrana: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. E. Sánchez Rodriguez: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. M.J. de Frutos Lobo: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. J. Vilaró: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.