Aspergillus species can cause lung disease by direct infection, such as invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA), aspergillosis, etc.; or by hypersensitivity reactions to fungal proteins, such as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA).1 We here describe a patient that simultaneously developed ABPA and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) in the context of an Aspergillus niger airway infection and discuss the overlapping criteria of these conditions.

A 27-year-old Indian male, resident in Portugal for the past two years, presented mild intermittent bronchial asthma. He developed progressive non-productive cough and dyspnoea over the course of six weeks, and was admitted to the emergency department for the sudden onset of intense right chest pain.

Physical examination was unremarkable. Blood tests revealed leucocytosis (13.1 × 109/L), with neutrophilia (10.7 × 109/L), eosinophilia (1.5 × 109/L) and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) 9.4mg/dL (normal <0.5). Imaging showed a 6 cm-long right hilar mass, extending to the pleura and enlarged hilar lymph nodes. Bronchoscopy observed bulky secretions obstructing the anterior segment of the right upper lobe (RB3). Cultures of bronchial aspirate, lavage and biopsies were all positive for Aspergillus niger. Eosinophils were abundant on bronchial aspirate, with Charcot-Leyden crystals, and in bronchial biopsies.

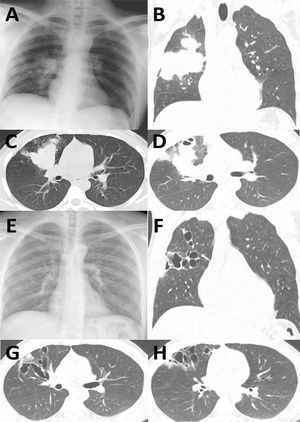

The patient was hospitalized and voriconazole was initiated. Two weeks later, voriconazole was changed to liposomal amphotericin B due to drug-induced hepatotoxicity. After three weeks of antifungal treatment, no clinical improvement was observed (increasing fever, neutrophilia 13.84 × 10^9/L, CRP 27.59mg/dL). Imaging showed a growing lung mass with suspected superinfection (Fig. 1A-D). Empirical piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin were initiated. After 10 days of antibiotic therapy, neutrophilia and CRP had diminished (8.9 × 10^9/L, 7.34mg/dL, respectively). However, anaemia developed (Hb 8.6g/dL, normal 13.0-17.5) and clinical manifestations continued to deteriorate, with asthenia, fever, dyspnoea and cough.

Comparison of chest X-ray and CT at admission (A-D, a 6 cm-long right hilar mass is observed, extending to the pleura and enlarged hilar lymph nodes) and 4 months after disease resolution (E-H, large varicoid bronchiectasis in both lungs can be observed, particularly in the right upper lobe.).

In view of the poor response to antifungals and antibiotics, alternative diagnoses were considered. Further investigations showed elevated total IgE (5175IU/mL, normal <100), eosinophilia (0.71 × 109/L), negative procalcitonin (while CRP again increased to 13.29mg/dL), positive p- antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) and anti-myeloperoxidase (MPO) (8.5IU/ml, negative <3.5), while c-ANCA and anti-proteinase 3 (PR3) were negative. Specific IgE (sIgE) and specific IgG (sIgG) to Aspergillus fumigatus were strongly positive (sIgE 9.16kU/L, normal <0.35; sIgG 281.00mgA/l, normal <83.00). Skin prick test to Aspergillus fumigatus was positive (3mm).

At this point, the patient fulfilled diagnostic criteria for both ABPA and EGPA (Table 1). Despite the initial evidence of fungal colonization/infection and subsequent bacterial superinfection, it was considered that T2 inflammation played the dominant role in the disease. Methylprednisolone was started at 1mg/kg/day, together with itraconazole. Nasal computed tomography (CT) scan during treatment with systemic glucocorticoids showed mild maxillary sinusitis.

Diagnostic criteria of IPA, ABPA, EGPA. Criteria fulfilled by the patient are indicated by “+”, while unfulfilled criteria are marked “-“. NA, not assessed; NT, not tested.

Clinical recovery was rapid and occurred after two days of glucocorticoids, with resolution of fever and subsequently of asthenia and cough. On day 10, CRP (0.49mg/dL), blood eosinophils (0.09 × 109/L) and haemoglobin (13.8g/dL) were all normal.

The patient was discharged asymptomatic 20 days after initiating systemic corticosteroids. Itraconazole was maintained for 20 weeks and corticosteroids were tapered until suspension. At the end of antifungal treatment, the chest X-ray was normal (Fig. 1E) and there was no relapse of the symptoms. Four months after discharge, CT scan showed reduced lung mass but large varicoid bronchiectasis in both lungs, particularly in the right upper lobe (Fig. 1F-H).

This is a rare case of simultaneous development of ABPA and EGPA in the context of Aspergillus niger pulmonary infection. The identification of Aspergillus in airway samples complicated ABPA/EGPA diagnosis. On hospitalization, “proven IPA” could not be confirmed (no open lung biopsy was performed), but the patient fulfilled the criteria for “putative IPA”2 (Table 1). Novel criteria for invasive fungal disease were published by the EORTC/MSGERC consensus,1 after the described episode occurred.

Aspergillus is known to contribute to the development of ABPA3 and concomitant IPA and ABPA have been described.4 In contrast, the role of Aspergillus in the pathophysiology of EGPA remains largely speculative.5 The relationship between ABPA and EGPA is also incompletely understood. Several diagnostic criteria are common to both diseases and differential diagnosis is recommended.6 Recently, reports described the sequential occurrence of allergic bronchopulmonary mycosis (ABPM) and EGPA, or vice versa.7 How one established disease may be predisposed to the other is unknown but may include eosinophil recruitment by Th2-driven ABPM, or EGPA lung tissue damage and sequelae predisposing to fungal colonization and subsequent hypersensitivity.

Concomitant ABPA and EGPA at presentation seem to be rarer than sequential development. In the case described here, no past investigations were available. However, the patient was largely healthy before this episode, and we consider that ABPA and EGPA occurred simultaneously. To the best of our knowledge, only three other cases of simultaneous ABPA/EGPA have been reported.7

The possibility that EGPA and ABPA may co-exist in the same patient has important clinical implications. Besides differential diagnosis at presentation, long-term follow-up of one disease should explore for “de novo” development of the other disease. A fine understanding of the mechanisms involved in ABPA, EGPA, or their simultaneous presentation, will be required for the choice of targeted therapies.

Data availabilityInformed consent was signed by the patient.

Authors' contributionsIAC and FSR were attending physicians during hospitalization and follow-up, collected the data and prepared the manuscript. ML, FL, CV and ER were attending physicians for the patient during hospitalization and collected patient's data. JSC and TA contributed to the diagnosis and the manuscript.