The incidence of cystic fibrosis (CF) in Portugal is estimated at 1:8000 live births, although there is a lack of accurate statistics. The average life expectancy has been steadily increasing and CF is no longer an exclusively pediatric disease.

ObjectivesCharacterize the Portuguese adult population with the diagnosis of CF.

MethodsRetrospective study based on clinical data of adult CF follow-up patients in the three specialized centers in Portugal where all of CF patients are seen, during 2012.

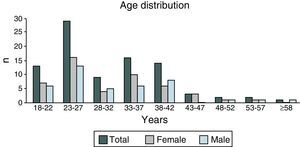

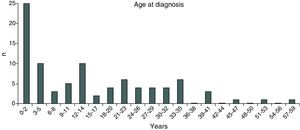

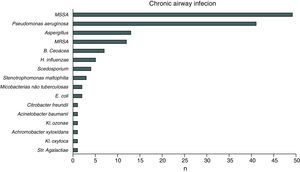

ResultsIn 2012, there were 89 follow-up patients, 48 (54%) female and 15 (17%) lung transplanted. The average age was 31.3±9 years. The median age at diagnosis was 13 years and 34 (38%) were diagnosed in adulthood. The most frequent mutation was F508del (54.9%). Of the 89 patients, 49 patients (56%) had pancreatic insufficiency, 7 (9%) were diabetic and 42 patients (47.7%) had a body mass index (BMI) <20kg/m2. As to ventilatory function, the average value of the forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1) was 58.45±28.59%. Only one of 77 patients did not have chronic airway infection. The most commonly isolated germ was methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus in 49 patients (55%). During 2012, two patients (2.2%) died at the ages of 21 and 36 years.

DiscussionThis study is the first description of the Portuguese adult CF population, which is particularly important since it can give us a better understanding of the real situation. A significant percentage of these patients were diagnosed in adulthood, which highlights the need for diagnostic suspicion in a patient with chronic lung disease and atypical manifestations.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common autosomal recessive monogenic disease in the Caucasian population. Its incidence in Portugal is estimated at 1:8000 live births, based on preliminary results obtained from the neonatal screening pilot project, ongoing for two years. This pilot project encountered almost only F508del homozygous, therefore its true incidence is perhaps underestimated. However, precise statistical data does not exist. In all 28 European Union countries, the prevalence is estimated to be 0.74 per 10,000 individuals.1 The average life expectancy has been steadily increasing and CF is no longer an exclusively pediatric disease, affecting more adults than before. In the 1940s to 1960s CF was usually fatal in early childhood because of the consequences of recurrent pulmonary infection and malnutrition due to pancreatic failure and subsequent mal-digestion of nutrients. Initial improvements in care included the introduction of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in the 1960s and enteric coated enzymes in the early 1980s to treat pancreatic insufficiency in combination with a high calorie and high fat diet. Systemic antibiotic therapy for lung infection and the development and use of inhaled antibiotic therapies over successive decades have been important therapeutic developments. The introduction of mucolytics including dornase alpha, hypertonic saline and more effective methods of airway clearance have contributed to the major therapeutic advances from the 1970s to the current era. These and other supportive therapies for complications of CF have been delivered by multidisciplinary teams in CF centers. Centralized care with dedicated CF teams has become and remains the cornerstone of care delivery in CF.15 According to the European Cystic Fibrosis Society patient registry (ECFSPR) data, the median predicted age of survival at 2010 was 43.5 years in UK.2 In Portugal there is no national data, however, according to CF adult follow-up patients in specialized centers, the average age is 30.7 years.3 In our country there are 300 follow-up patients in specialized CF outpatient clinics (less than expected considering the incidence in Portugal), and approximately one-third are adults. In this group, pulmonary disease tends to be more advanced and associated with several co-morbidities such as diabetes, metabolic bone disease, cancer, toxic effects and complications associated with lung transplantation.4

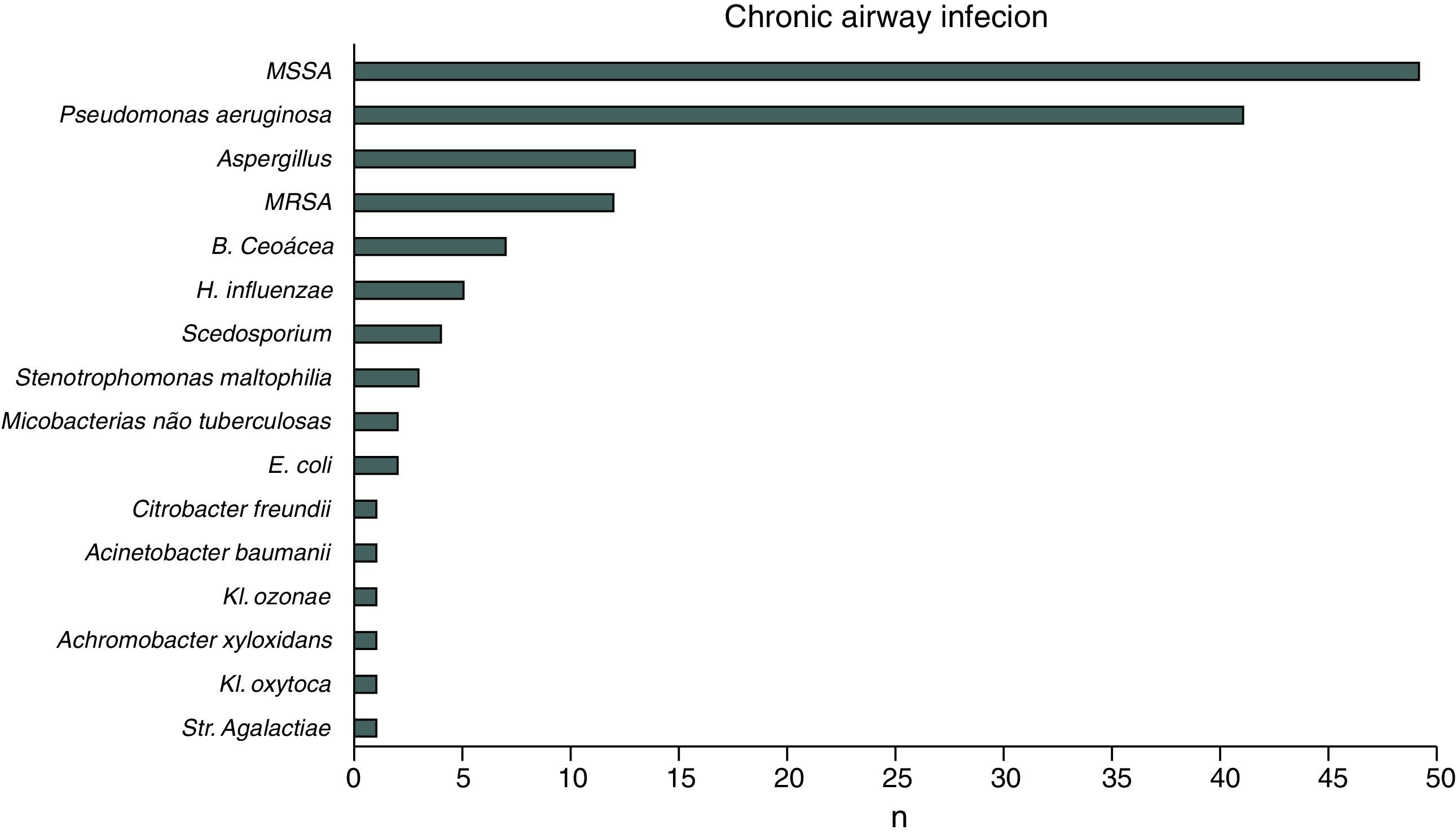

CF is caused by mutations in the long arm of chromosome 7, encoding the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR), which is expressed predominantly in the epithelial cells.5 So far more than 2000 mutations have been identified,6 the most common is F508del and the others are rare.7 Mutations in this gene cause changes in the transepithelial ion transport of chloride and the organ most affected is the lung, which is the greatest contributor to the morbimortality. It results in impaired mucociliary clearance and predisposition to airway infection.5 Surprisingly, infections are caused by a limited number of bacteria. In adults, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus are the most frequent microorganisms.8 Recent reports document an increasing incidence of new Gram-negative pathogens such as Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Alcaligenes xylosoxidans and Burkholderia cepacia complex.9

Even when aggressive treatment of the respiratory disease is employed, there is a progressive decline in lung function, with a moderate-severe impairment present in 60% of adults.10 When lung function is severely compromised lung transplantation may be indicated. In these patients, bilateral lung transplantation is the only option, given the chronic bronchial infection.

The disease is multisystemic and affects all organs that express CFTR, including not only lung but also pancreas, intestine, biliary tract, vas deferens, sweat and salivary glands.11

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency is present in 85% of patients with CF and the clinical manifestations (such as steatorrhoea and poor nutrition) are mostly dealt with by diet and pancreatic enzyme replacement. In some patients (8–15%), as time progresses, there is destruction of insulin-producing cells, resulting in endocrine pancreatic insufficiency, manifested by diabetes mellitus. Pancreatic sufficiency (15%) may be present at an older age and usually patients have milder lung disease and normal or borderline sweat electrolyte values.11

Usually only a small percentage of patients (3–5%) have liver disease, which manifests clinically as neonatal jaundice, hepatic steatosis or biliary cirrhosis. It is also possible to observe a micro-gallbladder and increased incidence of gallstones (12% of patients), which normally does not cause any symptoms and does not require treatment.11

Recurrent constipation and distal intestinal obstruction syndrome (previously known as meconium ileus equivalent) are features in older patients with CF.11

Approximately 97% of males with CF are infertile due to azoospermia attributed to congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens. Infertility may be the initial presentation for some males with mild disease. However, a male gender CF patient may have children, by puncturing the seminal vesicles, doing sperm collection and in vitro fertilization. In the female gender the ovulation is normal, but given the adverse conditions, there is a decrease in fertility due to anovulatory cycles. The presence of thick cervical mucus, which functions as a barrier to sperm, is another factor contributing to lower fertility.11

Sweat glands in CF patients do not show any histological abnormalities but have pronounced abnormalities in sodium-chloride homeostasis due to defective CFTR function. The consequence of this defect is a resultant sweat with a relatively elevated concentration of chloride and sodium compared with normal sweat. This landmark discovery led to the development of the sweat test for diagnosis in 1959.11 An increased concentration of electrolytes in the sweat may result in hyponatremic/hypochloremic dehydration secondary to salt depletion or hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis secondary to chronic salt loss. Once the diagnosis is known and regular salt replacement offered this problem is rarely seen.11

Despite the technological advances in recent years, in terms of diagnostic and therapeutic approach, CF remains a progressive and lethal chronic disease.

This study aims to characterize the Portuguese adult population diagnosed with CF followed in specialized centers during 2012.

MethodsRetrospective analysis based on clinical data of adult CF follow-up patients in the three specialized centers in Portugal (Centro Hospital e Universitário de Coimbra, Centro Hospitalar de São João, Porto and Centro Hospitalar de Lisboa Norte – Hospital de Santa Maria, Lisbon, Portugal), where all of CF patients are seen, in 2012. The following variables were analyzed: geographical distribution, gender, age (December 31st, 2012), age at diagnosis, mutations/CFTR genotype, nutritional status, pancreatic function, ventilatory function (FEV1), chronic bronchial infection, lung transplantation and mortality. The nutritional status was evaluated according to the World Health Organization and classified as underweight (BMI<18.5kg/m2), normal weight (BMI 18.5–24kg/m2), overweight (BMI 26–39kg/m2) and obesity (BMI>30kg/m2).12 The severity of lung disease was defined based on the forced expiratory volume in 1s (FEV1) and categorized as very severe (FEV1≤20%), severe (FEV1 21–40%) moderate (FEV1 39–69%), mild (FEV1 89–70%) and normal (FEV1≥90). Chronic airway infection was considered if, in a period of six months, three or more positive cultures of the same bacteria were isolated. The reference ranges of sweat test by the conductivity (semi-quantitative) method are >90mmol/L if positive for CF; 50–90mmol/L borderline (could be CF); <49mmol/L negative/normal.

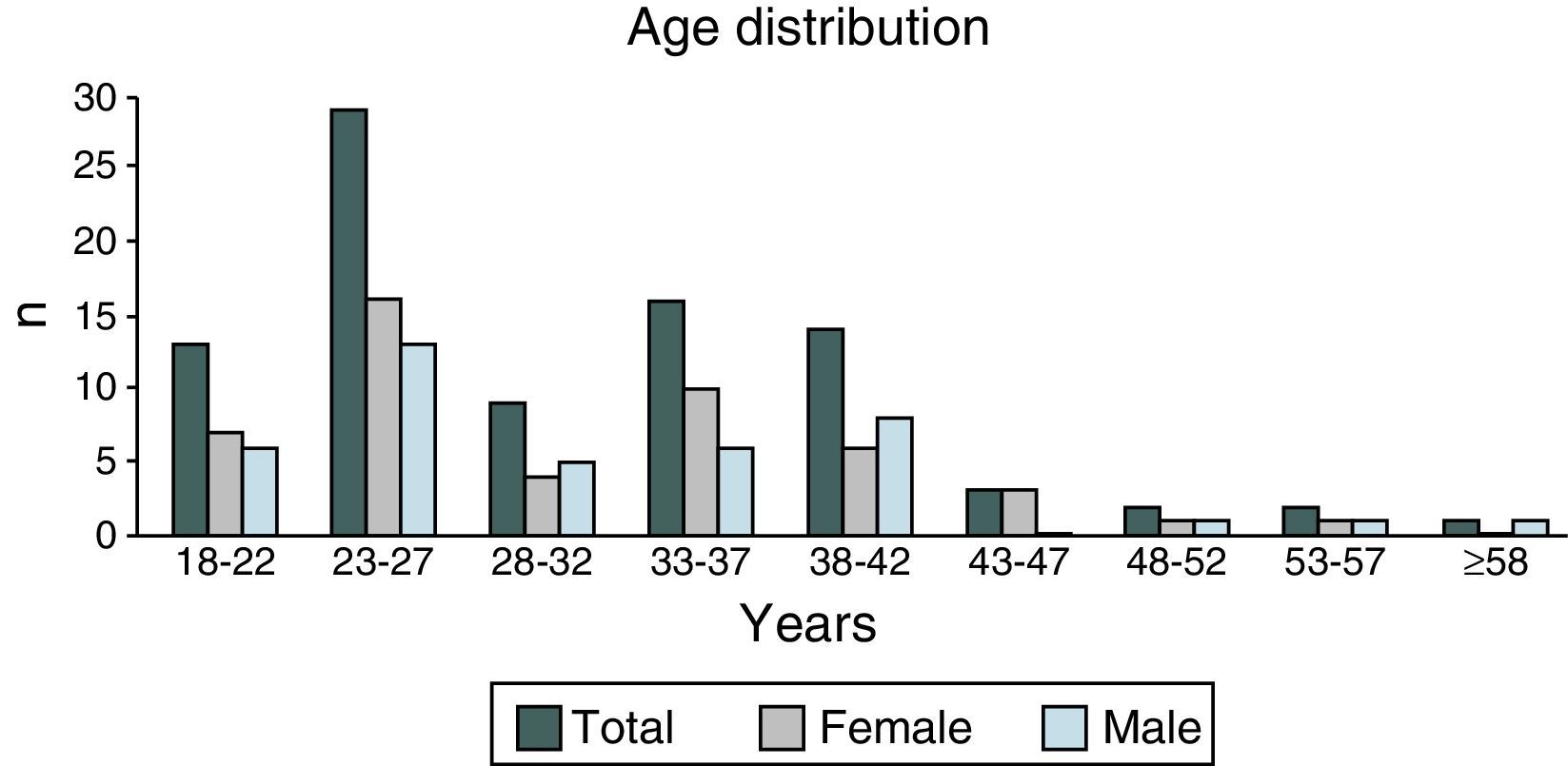

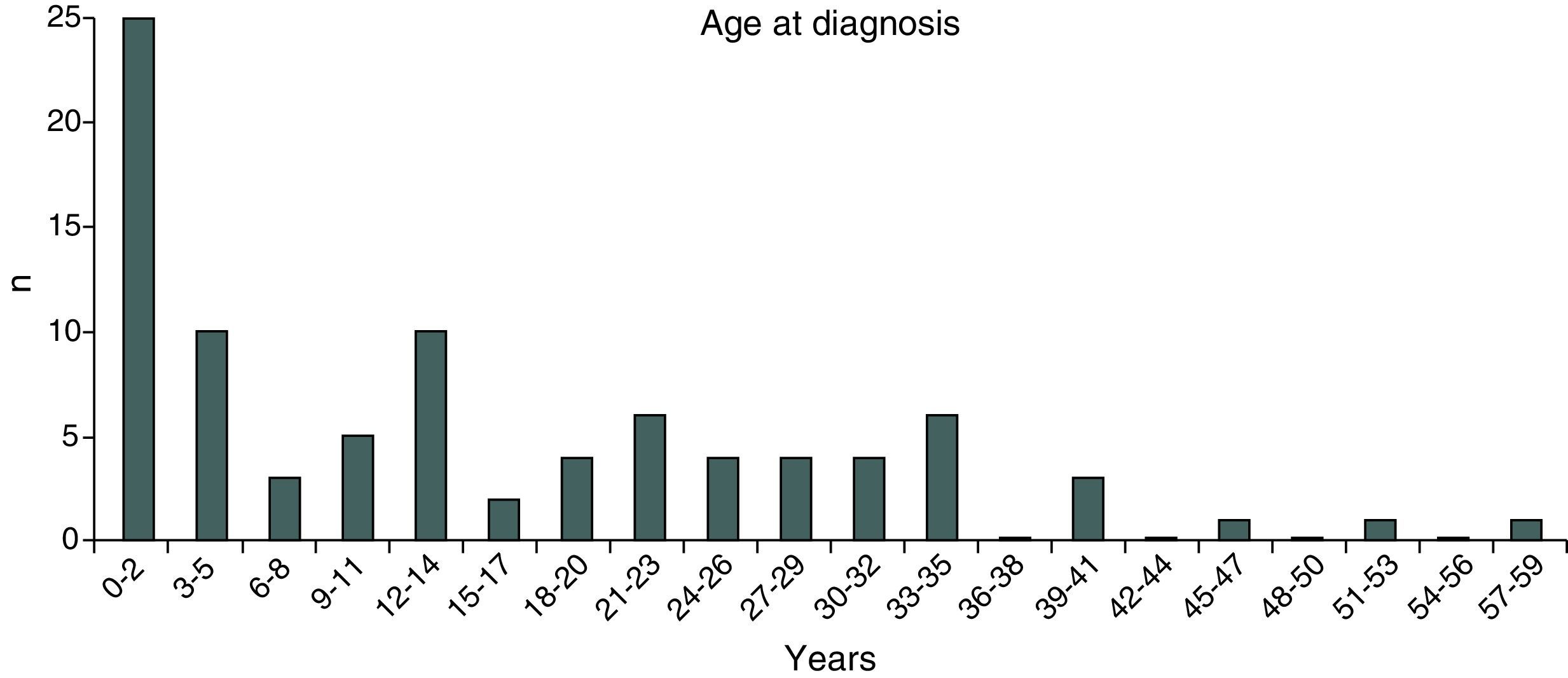

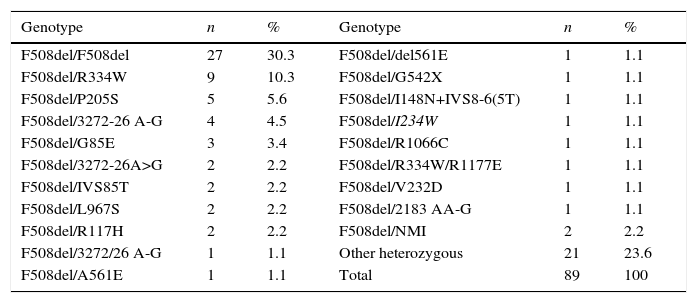

ResultsIn 2012, there were 89 adult follow-up patients with FQ were in Portugal, 42 at the Hospital de Santa Maria, in Lisbon, 24 at the Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra-Hospitais da Universidade de Coimbra and 23 at the Centro Hospitalar de São João, in Porto. Of the 89 patients, 48 (54%) were female and 41 (46%) were male gender. The average age was 31.23±9 years (minimum of 19 and maximum of 58 years). The age distribution was mostly between 23 and 27 years (Chart 1). The age at diagnosis ranged from two months to 58 years, with a median age of 13 years, and 34 (38%) were diagnosed in adulthood (Chart 2). The sweat test was positive in 85 (94%) patients, borderline in four (5%) and negative in one patient (1%). The genetic study of the CFTR locus was done for all patients. The most frequent mutation was F508del in 95 patients (54.9%), 27 patients (30%) were homozygotes and 41 (46%) heterozygous for this mutation. The second most frequent mutation was R334W, identified in 22 patients (12.7%). The different genotypes and their frequency are shown in Table 1. Of the 89 patients, 49 (56%) had pancreatic insufficiency and 7 (9%) were diabetic. Regarding nutritional status, mean body mass index (BMI) was 20.93±4.05kg/m2, of which 24 (27.3%) were underweight, 54 (61.4%) normal weight, 8 (9.1%) overweight and 2 (2.3%) obese. Of the 77 patients (excluding patients transplanted up to 2011), 3 (3.9%) had very severe ventilatory function, 15 (19.48%) severe, 31 (40.26%) moderate, 16 (20.78%) mild and 12 (15.58%) patients had normal ventilatory function. The average FEV1 value was 62.75±27.84%, with a minimum of 10.50% and a maximum of 133.90%. Considering all 77 patients, only one (1.3%) did not have chronic airway infection. Of the patients with chronic infection, 31 (40.3%) had only one microorganism isolated and 45 (58.4%) had more than two microorganisms. The most common microorganism was methicillin-sensitive S. aureus in 49 patients and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 41 patients. The frequency of microorganisms identified is shown in Chart 3. Of the patients undergoing lung transplantation (17%), 7 were female and 8 male gender. The average survival time after lung transplantation was 3.53±2.88 years, with a minimum of one year and a maximum of eight years. During 2012 two female patients (2.2%) died at 21 and 36 years, due to lung transplant rejection and sepsis with pulmonary origin, respectively.

Genotype frequency.

| Genotype | n | % | Genotype | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F508del/F508del | 27 | 30.3 | F508del/del561E | 1 | 1.1 |

| F508del/R334W | 9 | 10.3 | F508del/G542X | 1 | 1.1 |

| F508del/P205S | 5 | 5.6 | F508del/I148N+IVS8-6(5T) | 1 | 1.1 |

| F508del/3272-26 A-G | 4 | 4.5 | F508del/I234W | 1 | 1.1 |

| F508del/G85E | 3 | 3.4 | F508del/R1066C | 1 | 1.1 |

| F508del/3272-26A>G | 2 | 2.2 | F508del/R334W/R1177E | 1 | 1.1 |

| F508del/IVS85T | 2 | 2.2 | F508del/V232D | 1 | 1.1 |

| F508del/L967S | 2 | 2.2 | F508del/2183 AA-G | 1 | 1.1 |

| F508del/R117H | 2 | 2.2 | F508del/NMI | 2 | 2.2 |

| F508del/3272/26 A-G | 1 | 1.1 | Other heterozygous | 21 | 23.6 |

| F508del/A561E | 1 | 1.1 | Total | 89 | 100 |

NMI: No mutation identified.

This study is the first description of the Portuguese adult CF population, which is particularly important, since it gives a better understanding of the real situation. The average age of CF patients in our population (31.23±9 years) reflects the increased survival in this pathology, with a significant percentage of patients diagnosed in adulthood (38%).13 Newborn screening for CF started as a pilot project in Portugal in 2013 and will continue until the end of 2015. This screening when implemented in other European countries seems to prevent early CF-related deaths and leads to a substantial and prolonged health gain for patients with CF.7 This study highlights the need for diagnostic suspicion in a patient with chronic lung disease and atypical manifestations. The wide heterogeneity of mutations found in these patients complies with that described in South Europe.14 Good nutritional status and reasonable ventilatory function reflect not only a wide spectrum of clinical severity, as well as a more efficient treatment regime and very regular follow up, based on international recommendations. Therefore, specialized follow up is of utmost importance.

Lung transplantation is, increasingly, assumed to be a therapeutic alternative in the later stages of CF, and these patients have a better prognosis if they have this intervention.15

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.