In 2006, the Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho Hospital Centre Pulmonary Oncology Unit started performing EGFR (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor) mutation sequencing in selected patients with NSCLC and systematically in all patients since 2010, regardless of histology, smoking habits, age or sex. The aim of this study was to characterize the group of patients that carried out the sequencing between 2006-2010, to determine EGFR mutation frequency, to evaluate the overall survival and the survival after the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), in patients who performed this therapy in second and third line, knowing the EGFR mutation status.

MethodsDescriptive statistical analysis of patients who did EGFR sequencing in 2006-2010 and of overall survival in patients treated with TKI as 2nd and 3rd line therapy. Record of the material available for analysis and average delay of exam results, according to the material submitted.

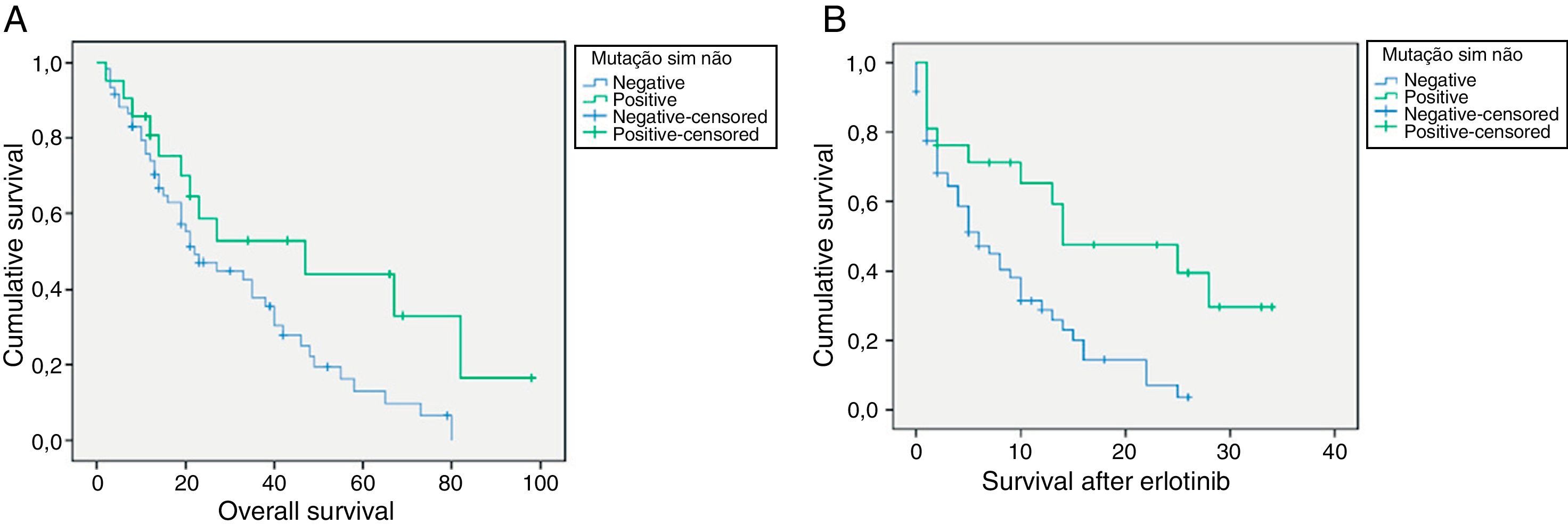

ResultsThe sequencing was performed in 374 patients, 71,1% males, 67,1% non/ex-smokers, 32,9% smokers, 57,8% adenocarcinoma and 23,5% squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The mutation was detected in 49 patients (13,1%). In all studied patients, the mutation rate was 9% in males and 23% in females. Median overall survival after erlotinib use of was 14 months for patients with positive EGFR mutation versus 6 months in not mutated patients (p = 0.003).

ConclusionOur group had an overall mutation rate of 13.1% with female, non-smokers, adenocarcinoma histology predominance. In selected patients (2006/2009), the mutation rate was 16%, in not selected patients (2010) the mutation rate was 10.4%. This study has permitted a better understanding of the EGFR mutation rate in the Portuguese population as welll as an evaluation of the patients survival after the use of of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, in second and third line therapy with previous knowledge of the EGFR mutational status. Statistical significant differences in survival were found in the two patient groups (EGFR mutated and non mutated).

The EGFR mutation research should be performed in all patients with NSCLC, giving the possibility to a considerable number of patients to perform a first line treatment with TKI (EGFR mutated patients) and the advantage of performing other chemotherapy schemes, when progression occurs.

Em 2006, a Unidade de Pneumologia Oncológica do Serviço de Pneumologia do Centro Hospitalar de Vila Nova de Gaia/Espinho iniciou a sequenciação da mutação do recetor do fator de crescimento epidérmico (EGFR) em doentes com CPNPC selecionados e desde 2010 realiza a sequenciação sistematicamente em todos os doentes, independentemente da histologia, hábitos tabágicos, idade ou sexo. O objetivo deste trabalho foi caracterizar o grupo de doentes que efetuou a sequenciação entre 2006-2010, determinar a frequência da mutação EGFR, avaliar as sobrevidas globais e após uso de inibidores da tirosina quinase (ITK), nos doentes que efetuaram esta terapêutica em 2.a e 3.a linha com conhecimento do estado da mutação do EGFR.

MétodosAnálise estatística descritiva dos doentes que efetuaram sequenciação EGFR em 2006-2010 e sobrevida mediana global nos doentes que efetuaefetuaram ITK em 2.a e 3.a linha. Registo do material disponível para análise e demora média de resultado do exame, de acordo com o material enviado.

ResultadosA sequenciação foi efetuada em 374 doentes, 71,1% sexo masculino, 67,1% não/ex-fumadores, 32,9% fumadores; 57,8% adenocarcinoma e 23,5% carcinoma epidermoide (CE). A mutação foi detetada em 49 doentes (13,1%). No total dos doentes estudados, a taxa de mutação foi de 9% no sexo masculino e 23% no sexo feminino. A sobrevida mediana global após o uso de erlotinib foi de 14 meses para os doentes com mutação positiva do EGFR versus 6 meses nos doentes não mutados (p = 0,003).

ConclusãoO nosso grupo teve uma taxa de mutação global de 13,1%, com predomínio no sexo feminino, não fumadores, histologia adenocarcinoma. Em doentes selecionados (2006/2009), a taxa de mutação foi de 16%; nos doentes não selecionados (2010) foi de 10,4%. Este estudo tem vindo a permitir um melhor conhecimento da taxa de mutação do EGFR na população portuguesa, bem como avaliar os resultados das sobrevidas dos doentes após uso de inibidores da tirosina quinase (ITK), efetuada em 2.a e 3.a linha com conhecimento prévio do estado da mutação do EGFR, tendo sido encontradas diferenças nas sobrevidas nos 2 grupos de doentes (mutados e não mutados) com significado estatístico.

A pesquisa mutação do EGFR deve ser efetuada em todos os doentes com CPNPC, dando possibilidade a um número considerável de doentes de poder efetuar um tratamento de 1.a linha com ITK (doentes mutados), bem como de poder usufruir de outros esquemas de quimioterapia, quando progredirem.

Prognostic and predictive factors in lung cancer are important for patient and doctor, because they provide a more accurate prognosis (in terms of recurrence of the disease, progression and survival), and help establish the best treatment.

The classic prognostic factors include smoking history, general health status and co-morbidities. Nowadays there are also molecular markers that have become prognostic factors, and the most carefully studied are: epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and KRAS mutation, which in association with histology are considered potential predictive factors.

Early identification of the subpopulation of patients most likely to respond to a particular treatment is currently the main goal of lung cancer treatment; this not only increases the probability of response but also avoids unnecessary treatment for those patients who are unlikely to benefit from it.

There is not a reliable lung cancer record in Portugal and so it is very difficult to define our national epidemiological profile or the actual NSCLC incidence rate and therefore difficult to make a clinical assessment of potential treatment.

In 2000 and 2002, the Portuguese Pulmonology Society Ontological Commission1, carried out a study involving 22 Portuguese hospitals, in which 4396 new lung cancer cases were registered; the most frequent histological subtype was adenocarcinoma and 76.9% of the cases were patients with advanced or metastatic disease.

Although it is our understanding that of these patients with advanced disease, only 10–12% might benefit from 1st line tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), the appearance of EGFR-TKI was significant for advanced or metastatic NSCLC treatment, first line in patients with EGFR mutation and even in second and third line therapy.

There are several clinical and molecular parameters that are useful for predicting which patients with NSCLC advanced disease are most likely to benefit from treatment with TK inhibitors, both for initial therapy or as second-line therapy. These indicators, from phase II2-5 and III6 studies which identified a number of clinical parameters associated with better clinical response, are adenocarcinoma, female gender, non-smoking and Asian ethnicity.7-9

Specific EGFR TK domain activating mutations (exons 18-21) are usually associated with an increased response to TK inhibitors, erlotinib or gefitinib, which occur, according to the literature, in Europe in 10-15% of patients with NSCLC and have easily manageable side effects.

The “gold standard” method for EGFR mutation analysis is direct DNA sequencing (exons 18-21). The percentage of mutations in each exon is still controversial; the majority of studies, including the Spanish group10, only studied exons 19 and 21 (and only the mutation Leu858Arg). There has also been mention of mutations also in exons 18 and 20 and some of which had predictive value of response.11 Values such as 5% were found in exon 18, 49% in exon 19, 1% in exon 20 and 45% in exon 21. The positive predictive value of Gly719 mutation in exon 18, and the negative predictive value of exon 20 insertions12 are well established. Penzel et al13 in 1047 analyzed cases, found a 15,6% mutation rate (exon 18–10,4%, exon 19–49,7%, exon 20–5,5% exon 21–34,4%).

There is also no also consensus as to which group of patients should be examined for EGFR mutation and studies have typically excluded patients with epidermoid tumors and heavy smokers.

Neither is there a defined consensus about which is the best biopsy value (primary tumor vs metastases) for the mutation study; however, whenever possible, the first study of EGFR mutations is performed in primary tumor and not in the metastases. It is not common to perform a new puncture or biopsy in patients who are progressing when treated with ITK. In about 50% of progression cases Thr790Met (exon 20) mutation occurs. This mutation provides resistance to treatment with TKIs, but that is a secondary mutation which appears only after treatment and resistance acquisition and is only very rarely a primary mutation (although some authors argue that it may already have been present in sub-clones of residual tumor cells before treatment with TKIs)14.

The best responses to treatment are obtained in patients with exon 19 deletions and in exon 21 Leu858Arg mutation, although results tend to be slightly lower than exon 19 deletion; exon 18 Gly719 mutations and exon 21 Leu 861 are associated with a good response. The evidence for this is clinical and experimental (in vitro)14.

In 2006, Gaia-Espinho Hospital Center (CHGE) Pulmonology Service, Pulmonary Oncology Unit (POU), started performing EGFR gene mutation sequencing in collaboration with IPATIMUP (Oporto University Molecular Pathology and Immunology Institute) in selected patients and by this time erlotinib had been approved in Portugal for use in 2nd and 3rd line therapy. In 2010, with the approval of gefitinib for first line therapy, systematic sequencing was started in all NSCLC patients regardless of histology, stage, smoking habits or sex, and treatment with Gefitinib in 1st line all patients with positive EGFR mutation.15 We therefore decided on a prospective epidemiological data collection.

2Material and MethodsWe present the results of a continuous record, of research for EGFR mutations in patients with NSCLC, which was carried out in the CHGE Pulmonology Department between 2006 and 2010. We evaluated the results obtained after 2nd and 3rd line treatment with ITK in NSCLC patients with advanced disease who were studied for EGFR mutation. The 1st-line treatment results in mutated patients are not presented, as the number of cases is still small.

Between 2006 and 2009, the inclusion criteria for the EGFR mutations study were adenocarcinoma histology, non-smokers or former smokers, regardless of gender. In 2010, the inclusion criteria were diagnosis of NSCLC (regardless of gender), disease stage or smoking habits. Patients were classified according to their smoking habits as: smokers, former smokers (patients that had given up for more than 12 months) and nonsmokers. The material available for analysis and the average delay of exam results, according to the material submitted were also taken into account.

In patients with advanced stage treated in second and 3rd line with erlotinib between 2006 and 2010, the evaluated parameters included age, sex, smoking, histology, TNM stage at presentation, chemotherapy prior schemes, EGFR mutational state and overall survival according to mutational status, median overall survival after erlotinib.

All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) software version 17.0.

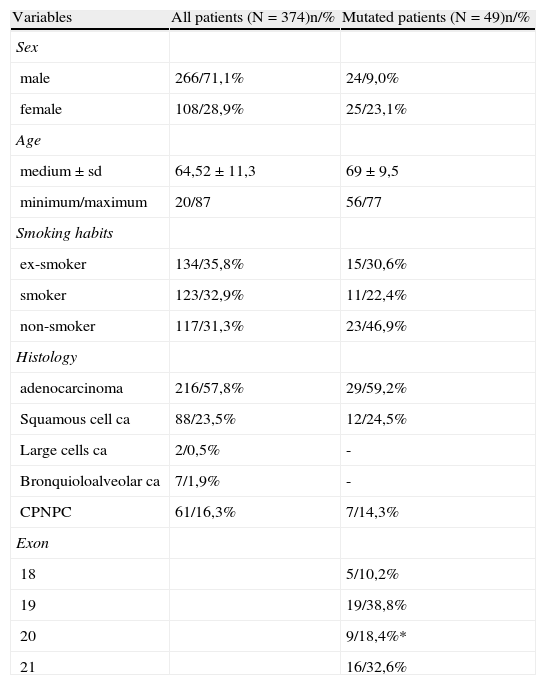

3ResultsIn the period between January 1st 2006 and December 31st 2010, EGFR sequencing was carried out in 374 patients with NSCLC (248 patients between 2006 and 2009 and 126 patients in 2010). Of the total number of analyzed patients, 266 (71.1%) were male and 108 (28.9%) female. The average age was 64.5±11.3 years. 35.8% were former smokers, 31.3% non-smokers and 32.9% smokers. The predominant histological type was adenocarcinoma,57.8%, followed by squamous cell carcinoma - 23.5% (Table 1).

Characterization of the total group of patients and EGFR mutation frequency (* 6,2% were resistance mutations).

| Variables | All patients (N=374)n/% | Mutated patients (N=49)n/% |

| Sex | ||

| male | 266/71,1% | 24/9,0% |

| female | 108/28,9% | 25/23,1% |

| Age | ||

| medium±sd | 64,52±11,3 | 69±9,5 |

| minimum/maximum | 20/87 | 56/77 |

| Smoking habits | ||

| ex-smoker | 134/35,8% | 15/30,6% |

| smoker | 123/32,9% | 11/22,4% |

| non-smoker | 117/31,3% | 23/46,9% |

| Histology | ||

| adenocarcinoma | 216/57,8% | 29/59,2% |

| Squamous cell ca | 88/23,5% | 12/24,5% |

| Large cells ca | 2/0,5% | - |

| Bronquioloalveolar ca | 7/1,9% | - |

| CPNPC | 61/16,3% | 7/14,3% |

| Exon | ||

| 18 | 5/10,2% | |

| 19 | 19/38,8% | |

| 20 | 9/18,4%* | |

| 21 | 16/32,6% |

Positive mutation patients (N=49).

10.1% of patients were in TNM stage I, 2.4% of cases in stage II, 5.8% in stage IIIA and in stage IIIB / IV 81.6% of cases.

EGFR gene mutations were detected in 49 out of 374 patients, corresponding to a 13.1% mutation rate (the mutation rate was 9% in males and 23% in females). Of the total number of mutated patients, 46.9% were non-smokers and 59.2% were adenocarcinomas. (Table 1)

When considered separately, the mutation rate in selected patients (2006/2009) was 16.3% vs 10.4% in 2010, the year the mutation study began to be carried out on all patients with NSCLC.

The exon distribution was: 10.2% in exon 18, 38.8% in exon 19 and 18.4% in exon 20 (6.2% were of resistance), 32, 7% in exon 21.

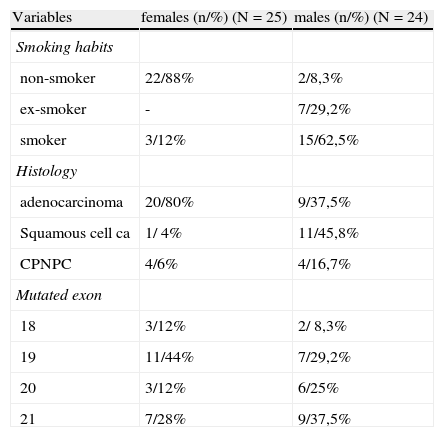

In female patients with positive mutation (n=25), most were non-smokers (22/88,0%) and had an adenocarcinoma histology predominance (20/80,0%). In this subgroup, 44% of mutations occurred in exon 19, 28% in exon 21, 12% in exon 18:12% in exon 20. (Table 2)

Characterization of male/female EGFR mutated patients.

| Variables | females (n/%) (N=25) | males (n/%) (N=24) |

| Smoking habits | ||

| non-smoker | 22/88% | 2/8,3% |

| ex-smoker | - | 7/29,2% |

| smoker | 3/12% | 15/62,5% |

| Histology | ||

| adenocarcinoma | 20/80% | 9/37,5% |

| Squamous cell ca | 1/ 4% | 11/45,8% |

| CPNPC | 4/6% | 4/16,7% |

| Mutated exon | ||

| 18 | 3/12% | 2/ 8,3% |

| 19 | 11/44% | 7/29,2% |

| 20 | 3/12% | 6/25% |

| 21 | 7/28% | 9/37,5% |

In mutated men (n=24), 91.7% were smokers or ex-smokers and the predominant histological type was squamous cell carcinoma, in 45.8% of patients. Mutations occurred 37.5% in exon 21, 29.2% in exon 19, 25% in exon 20 and 8.3% in exon 18. (Table 2)

Non-smoker mutated patients (23), were mostly female (21/91, 3%), 78.3% were adenocarcinomas, 17.4% NSCLC and 4.3% squamous cell carcinomas. In the majority of non-smokers, mutation occurred in exon 19 (43.5%) and exon 21 (34.8%), followed by exon 18 (13.0%) and exon 20 (4.3%).

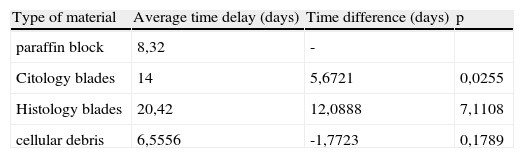

The average delay-time for obtaining a sequencing result16, varied according to the type of material available for study, using blades the average was 20 days, with paraffin block it took 8.32 days and with cellular debris (with fresh products EBUS BAT and other punctures in Pathology) the result was available within 6.5 days on average. (Table 3).

Average time-delay in obtaining a sequencing result according with the type of material available for study.

| Type of material | Average time delay (days) | Time difference (days) | p |

| paraffin block | 8,32 | - | |

| Citology blades | 14 | 5,6721 | 0,0255 |

| Histology blades | 20,42 | 12,0888 | 7,1108 |

| cellular debris | 6,5556 | -1,7723 | 0,1789 |

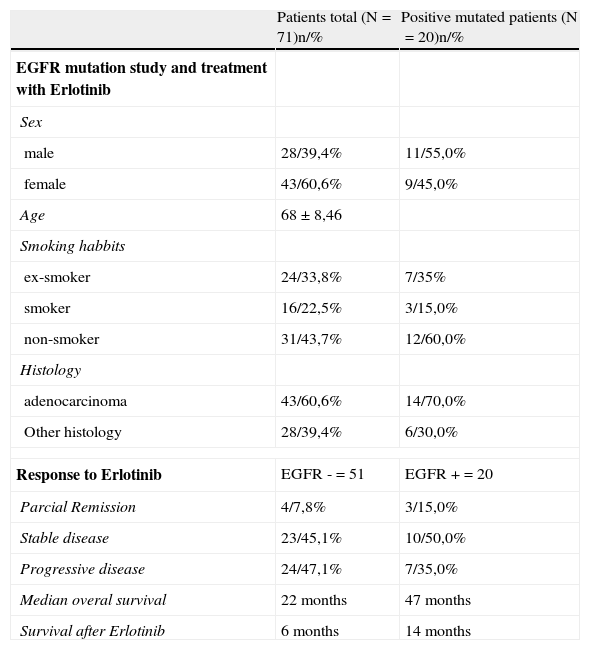

Of the total patients sequenced, 71 with advanced or metastatic stage had 2nd and 3rd line treatment with erlotinib 150mg/day, up until death, disease progression or unacceptable toxicity levels. Within this subgroup of patients, there were females (43/60,6%), non-smokers (31/43,7%) and predominantly patients with adenocarcinoma histology (43/60,6%). EGFR mutation was positive in 20 patients (19.2%), 55% men and 45% women, mainly non-smokers (12/60, 0%) and with adenocarcinoma histology (14/70%). (Table 3) Regarding overall response to treatment with erlotinib in patients with negative EGFR mutation (n=51), 47.9% (24) had progressive disease, 45,1% (23) stable disease and 7.8% (4) were in partial remission.

In the subgroup of patients with positive EGFR mutation treated with erlotinib (n=20), 35,0% (7) showed progressive disease, 50.0% (10) stable disease and 15.0% (3) partial remission, in other words as would be expected there was better disease control in patients with positive EGFR mutations when compared to patients with negative mutation (65.0% vs 52.9%). (Table 4)

Demographic data concerning the group of patients treated with erlotinib and treatment response.

| Patients total (N=71)n/% | Positive mutated patients (N=20)n/% | |

| EGFR mutation study and treatment with Erlotinib | ||

| Sex | ||

| male | 28/39,4% | 11/55,0% |

| female | 43/60,6% | 9/45,0% |

| Age | 68±8,46 | |

| Smoking habbits | ||

| ex-smoker | 24/33,8% | 7/35% |

| smoker | 16/22,5% | 3/15,0% |

| non-smoker | 31/43,7% | 12/60,0% |

| Histology | ||

| adenocarcinoma | 43/60,6% | 14/70,0% |

| Other histology | 28/39,4% | 6/30,0% |

| Response to Erlotinib | EGFR -=51 | EGFR +=20 |

| Parcial Remission | 4/7,8% | 3/15,0% |

| Stable disease | 23/45,1% | 10/50,0% |

| Progressive disease | 24/47,1% | 7/35,0% |

| Median overal survival | 22 months | 47 months |

| Survival after Erlotinib | 6 months | 14 months |

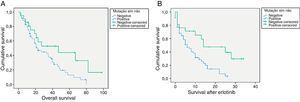

For EGFR mutation positive patients treated with erlotinib the overall survival rate vs. non-mutated was 47 vs 22 months (p=0.038), respectively. (Fig. 1) The average survival rate after treatment with erlotinib in the positive EGFR mutation group was also higher in this subgroup when compared with patients with negative mutation (14 vs 6 months, respectively, p=0.003). (Fig. 1).

4DiscussionOur group of patients showed a global (2006-2010) EGFR mutation rate of 13.1%. The fact that between 2006 and 2009 there was patient selection has to be taken into account, when the mutation rate was 16% vs 10.4% in 2010 when the mutation study was performed on all patients with NSCLC regardless of sex and stage. These figures add value to our knowledge about EGFR mutation rate in the Portuguese population. The European prevalence EGFR mutations in lung cancer studies, was 10% in unselected patients. In Spain, Rosell et al, found a mutation rate of 16.6%10, in a selected patients group with NSCLC in advanced stages. The follow-up of our work (which in 2011 and 2012 has also included an unselected population) will give a reliable definition of the EGFR mutation profile in the Portuguese population and confirm the data presented here, which includes data on the presence of the mutation in male patients, squamous cell carcinomas and some smokers. The difference in mutation rates however is very significant as regards the 2 sexes, adenocarcinoma being responsible for most cases.

It was possible to perform the EGFR gene sequencing in various types of diagnostic samples. DNA sequencing from cellular debris (fresh or after cell block) was faster than paraffin block or blades. This difference was statistically significant and impacted on when treatment started; it was only possible when there was close collaboration between the various elements involved in lung cancer diagnosis (Oncology, Bronchology, Interventional Radiology and Pathology). In peripheral tumors or whenever it is possible to perform aspirative biopsies, it should a priority to send this fresh material so as to obtain faster results (6.5 days after sending samples).

EGFR mutation study should be carried out routinely in all patients diagnosed with NSCLC, and its use should be facilitated in all hospitals treating lung cancer, to support proper treatment, and to consider the use of TKI 1st-line in mutated patients, which controls the disease better than conventional chemotherapy protocols. All these assumptions are based on treatment response and overall survival rates in the group of patients treated with TKI.16–18

The results of our sample in 2nd and 3rd line treatment showed statistical significance in the group of patients with positive EGFR mutation, compared to patients with negative mutation, despite the fact that the presence of EGFR mutation is not a mandatory condition for starting treatment. We still do not have enough patients to present the results of the mutated patients with 1st line treatment with TKIs.

5Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Castro, AS Estudo da mutação do recetor do fator de crescimento epidérmico, durante 5 anos, numa população de doentes com cancro do pulmão de não pequenas células. Rev Port Pneumol 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rppneu.2012.08.002