GOLD 2017 report proposed that the combined COPD assessment should be done according only to symptom burden and exacerbation history in the previous year.

ObjectiveThis study aims to investigate the change in the COPD groups after the GOLD 2017 revision and also to discuss the evaluation of group C and D as a single group after the GOLD 2019 report.

MethodThe study was designed as a cross-sectional. 251 stable COPD patients admitted to our out-patient clinic; aged ...40 years, at least one-year diagnosis of COPD and ...10 pack-year smoking history were consecutively recruited for the study.

ResultsIn GOLD 2017, a significant difference was found between the distribution of all groups compared to GOLD 2011 (P...=...0,001). 31 patients included in group C were reclassified into group A and 37 patients in group D were reclassified into group B. The FEV1 values of group A and B patients were significantly low and group C and D patients had had exacerbations in more frequently the previous year in GOLD 2017 compared to GOLD 2011.

ConclusionAfter the GOLD 2017 revision, the rate of group C patients decreased even more compared to GOLD 2011 and the group C and D may be considered as a single group in terms of the treatment recommendations with the GOLD 2019 revision. We think that future prospective studies are needed to support this suggestion.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) started its activities in 1998 to increase awareness of COPD all over the world and develop a common approach to the assessment and treatment of the disease. Their first report was published in 2001 with the title ...Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD..Ñ.1 In the GOLD 2007 report, forced expiratory volume in 1...s (FEV1) value was the most important determinant for the evaluation and treatment decision of COPD patients.2 However, clinical studies have shown that there is a poor relationship between FEV1, symptom status and quality of life and also FEV1 is not sufficient alone to predict exacerbations and treatment response.3,4 Thus, for the first time in the GOLD 2011 report, a combined assessment, including FEV1 as well as a history of exacerbation and symptom status, was proposed for the assessment and treatment decision of the disease.5 However, it was observed that this evaluation method was not useful in daily practice and that compliance with treatment recommendations according to GOLD 2011 was low worldwide.6,7 On the other hand, combined evaluation could not be shown to be superior to spirometric staging, either as a predictor of mortality or other health outcomes.8 The results of these studies required the 4th major revision in GOLD 2017 report.9 It recommended that the combined COPD assessment should be done according only to symptom burden and exacerbation history in the previous year. However, the GOLD 2017 ABCD classification could not predict all-cause and respiratory mortality more accurately than the GOLD 2007 and 2011 classifications.10 Finally, with the GOLD 2019 revision, very important changes were proposed for the pharmacological treatment in stable COPD. This study aims to investigate the change in the COPD groups after the GOLD 2017 revision and also to discuss whether groups C and D should be considered as a single group in terms of treatment after GOLD 2019 revision.11

Material methodThe study was designed as single-center and cross-sectional. 251 stable COPD patients admitted to our out-patient clinic consecutively were recruited in the study. Inclusion criteria were as follows: aged ...40 years, at least one-year diagnosis of COPD according to the GOLD classification with baseline post-bronchodilator FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio of less than 0.7, and at least 10 pack-year smoking history. Exclusion criteria were as follows: having COPD exacerbation within the past six weeks before enrollment, patient...s with incompatible pulmonary function tests (PFTs) or those unable to complete the case report form were excluded from the study. The case report form which included patients demographic, clinical and laboratory details (age, gender, smoking history, comorbidities, COPD assessment test (CAT), modified Medical Research Council (mMRC), exacerbation history, PFTs) was completed for each patient. We evaluated the asthma-COPD overlap according to the existing clinical and laboratory data of the patients. The patients who fulfilled two major or one major and two minor criteria were diagnosed as ACO. The major criteria were as follows: a very positive bronchodilator response (>400...mL0 and >15% increase in forced expiratory volume in 1...s (FEV1)), sputum eosinophilia or a previous diagnosis of asthma. Minor criteria were an increased total serum IgE, previous history of atopy or a positive bronchodilator test (>200...mL and >12% in FEV1) on at least two occasions.12

The pulmonary function test was performed if the patient had not been tested within the previous 6 months or the test was not valid. Spirometry was performed using a Sensor Medics model 2400 (Yorba Linda, California, USA) in accordance with the GOLD guidelines, and COPD was classified by their FEV1% predicted: stage1 (mild); FEV1 ...80%, stage 2 (moderate); 50%... FEV1<80%, stage 3 (severe); 30%... FEV1 <50% and stage 4 (very severe); FEV1<30%.2 All patients were divided into four risk/symptom categories according to both GOLD 2011 and 2017 reports: low risk, fewer symptoms (A); low risk, more symptoms (B); high risk, fewer symptoms (C); and high risk, more symptoms (D). Based on this categorization the cut-off points for risks; exacerbations in the previous year.........2 or ...1 leading to hospital admission and the cut-off points for symptoms; CAT scores ...10 and/or mMRC ...2 were chosen according to the GOLD 2017 classification (9). Unlike the 2017 report, the patients whose predicted FEV1% was less than 50% were included in the high-risk group according to the GOLD 2011 classification.5

An informed consent was taken from each patient. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Biruni University.

Statistical analysisThe normality of the distribution of continuous variables was tested by the Shapiro Wilk test. Mann...Whitney U test (for non-normal data) was used to compare two independent groups and the Chi-square test was used to assess the relationship between categorical variables. To compare non-normal data across more than 3 categories Kruskal Wallis and Dunn multiple comparison tests were applied. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS for Windows version 22.0 and a p-value <0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results251 patients (average age of 64.4........8.2 years and 88% male) were included in the study. 129 patients (51.4%) had at least one comorbidity. Hypertension (85 patients; 33.1%), coronary artery disease (37 patients; 14.7%), diabetes mellitus (31 patients; 12.7%) and gastroesophageal reflux (20 patients; 8%) were the most common comorbidities, respectively. Two hundred and fifteen patients were recorded with or without ACO. We accepted 36 patients as missing due to their non-classification as ACO or not with respect to their current clinical and laboratory data. Twenty-seven patients were evaluated as ACO in the study. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients are given in Table 1. When the proportions of the two groups were compared with McNemar...Bowker Test according to two sequential GOLD, 2011 and 2017, a significant difference was found between all groups (P...=...0,001). 31 patients (31/47;66%) included in group C were reclassified into group A and 37 patients (37/129;28.7%) in group D were reclassified into group B according to GOLD 2017 because they had no history of frequent exacerbations but only their predictive FEV1 was below 50%. Therefore, while the rate of group C and D patients decreased, the rate of group A and B patients increased in all patients.

Demographic and clinical features of the patients.

| Demographic and clinical features of the patients | |

|---|---|

| Patients, n; % | 251;100% |

| Male, n; % | 223; 88% |

| GOLD grade I, n; % | 11; 4.4% |

| GOLD grade II, n; % | 92; 36.7% |

| GOLD grade III, n; % | 95; 37.8% |

| GOLD grade IV, n; % | 53; 21.1% |

| ACO, n; %* | 27; 10.8% |

| The number of patients with at least one comorbidity, n; % | 129; 51.4% |

| Age (year), mean........std | 64.4........8.2 |

| Smoking (pack-years), mean........std | 45.7........25 |

| COPD duration (year), mean........std | 7.8........5 |

| FVC % pred, mean........std | 60.2........18 |

| FEV1 % pred, mean........std | 46.6........18 |

| FEV1/FVC, mean........std | 55.7........10.3 |

| Blood eosinophil count (per ..L), mean........std | 242.8........178 |

| The rate of blood eosinophil (%), mean........std | 2.7........2.4 |

| CAT score, mean........std | 12.1........8.4 |

| mMRC dyspnea score, mean........std | 1.63........1.22 |

| The number of exacerbations in previous year (moderate and severe ), mean........std | 2........3.6 |

| GOLD 2011 % (A/B/C/D) | 19.5/10.4/18.7/51.4 |

| GOLD 2017 % (A/B/C/D) | 31.9/25.1/6.4/36.7 |

Abbreviations: GOLD, global Initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ACO, Asthma-COPD overlap; % pred, percent predicted; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1...s; CAT, COPD assessment Test; mMRC, Modified Medical Research Council Scale.

Note: * data of 36 patients are missing.

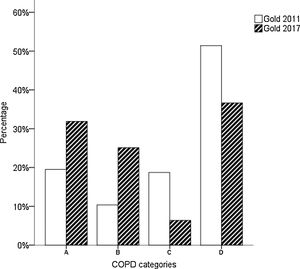

The distrubition of COPD categories according to GOLD 2017 is given in Fig. 1. It was observed that the group C ratio which is already lower than other groups, decreased more with the GOLD 2017 revision.

Pulmonary function values of GOLD 2017 group A and B patients were significantly lower than GOLD 2011 and also group A and B did not include patients with stages 3 and 4 in GOLD 2011. However, with the new classification (GOLD 2017), 31.3% of group A patients consisted of stage 3, 7.5% of them consisted of stage 4 patients, 42.9% of group B patients consisted of Stage 3 and 14.3% of them consisted of stage 4 patients. There was no difference in symptom scores (mMRC and CAT) and comorbidities between the groups according to the old and new classification. It was observed that GOLD 2017 group C and D patients had exacerbated more frequently in the previous year than GOLD 2011 group C and D patients. A comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics of the groups in GOLD 2011 and 2017 is given in Table 2.

The distribution of COPD groups by GOLD 2011 and GOLD 2017 and comparison in demographic, clinical and laboratory features.

| Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 2011 | 2017 | 2011 | 2017 | 2011 | 2017 | 2011 | |

| Age (years), mean........SD | 64........7.8 | 65........7.5 | 65........8 | 63.9........8.2 | 65.8........7.8 | 63.6........8.2 | 64.1........8.7 | 64.6........8.5 |

| Male, n (%) | 76(95) | 45(91.8) | 51(81) | 20(76.9) | 12(75) | 43(91.5) | 84(91.3) | 115(89.1) |

| Smoking index (pack-years) | 45........25.9 | 45.6........28.7 | 45.6........26.2 | 41.8........16.9 | 36.9........19.1 | 41.5........20.4 | 48........24.3 | 48........26.3 |

| COPD duration (year) | 6.6........5.3 | 6.7........5.4 | 8.6........5.2 | 7.1........4.2 | 7.1........4.3 | 6.7........4.9 | 8.5........4.8 | 8.8........5.1 |

| Post-bronchodilator FEV1(L) | 1.7........0.5 | 1.9........0.5* | 1.3........0.6 | 1.9........0.4* | 1.2........0.3 | 1.2........0.3 | 1........0.4 | 1........0.4 |

| Post-bronchodilator FEV1 % pred | 55.9........16.1 | 65.9........11.4* | 48.1........16.7 | 65.4........8.3* | 45........16.2 | 41.8........11.1 | 37.2........16.1 | 36.9........14.3 |

| Post-bronchodilator FVC (L) | 2.6........0.7 | 2.8........0.6* | 2.1........0.8 | 2.6........0.6* | 2.1........0.5 | 2.2........0.5 | 2.5........6.2 | 2.3........5.3 |

| Post-bronchodilator FVC % pred | 67.7........15.7 | 76.4........11.4* | 61.4........18.5 | 74.7........10.4* | 61.2........16.5 | 56.5........13.5 | 52.7........17.3 | 52.4........17.2 |

| Post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC | 59.9........7.6 | 62.7........5.4 | 57.1........10.2 | 64.5........6.4* | 53.4........12.3 | 54.8........9.9 | 51.5........10.5 | 51.6........10.1 |

| Blood eosinophil count | 268.4........206.1 | 267.7........214.1 | 240.5........179 | 263.8........215.1 | 262.5........141.3 | 263.7........177 | 221.7........157 | 222.4........154 |

| The rate of blood eosinophils | 2.9........1.8 | 2.9........1.8 | 3........3.8 | 3........2.2 | 2.9........2.2 | 2.9........1.9 | 2.4........1.5 | 2.6........2.8 |

| CAT score | 5.2........2.5 | 4.8........2.5 | 13.4........5.4 | 12.2........4.6 | 4.8........2.7 | 5.6........2.5 | 18.5........8.6 | 17.3........8.1 |

| mMRC dyspnea score | 0.6........0.6 | 0.6........0.6 | 1.9........1 | 1,5........1 | 0.8........0.5 | 0.6........0.5 | 2.5........1 | 2.4........1 |

| The number of exacerbations (moderate and severe) | 0.3........0.5 | 0.2........0.4 | 0.3........0.6 | 0.4........0.6 | 4.1........3.4 | 1.7........2.8* | 4.3........4.7 | 3.2........4.3* |

| GOLD stage 1 n (%) | 7 (8.8) | 7 (14.3) | 2 (3.2) | 2 (7.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2,2) | 2 (1.6) |

| GOLD stage 2 n (%) | 42 (52.5) | 42 (85.7)* | 25 (39.7) | 25 (92.6)* | 6 (37.5) | 6 (12.8) | 20 (21.7) | 20 (15.6) |

| GOLD stage 3 n (%) | 25 (31.3) | 0 (0)* | 27 (42.9) | 0 (0)* | 7 (43.8) | 32 (68.1) | 35 (38) | 62 (48.4) |

| GOLD stage 4 n (%) | 6 (7.5) | 0 (0) | 9 (14.3) | 0 (0)* | 3 (18.8) | 9 (19.1) | 35 (38) | 44 (34.4) |

| The number of patients with at least one comorbidity, n (%) | 42 (57.5) | 32 (65.3) | 35 (55.6) | 17 (65.4) | 9 (56.3) | 19 (40.4) | 43 (46.7) | 61 (47.3) |

| Hypertension | 25 (31.3) | 19 (38.8) | 25 (39.7) | 13 (50) | 4 (25) | 10 (21.3) | 29 (31.5) | 41 (31.8) |

| Coronary artery disease | 13 (16.3) | 10 (20.4) | 10 (15.9) | 6 (23.1) | 2 (12.5) | 5 (10.6) | 12 (13) | 16 (12.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (8.8) | 5 (10.2) | 9 (14.3) | 5 (19.2) | 2 (12.5) | 4 (8.5) | 14 (15.2) | 18 (14) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 6 (7.5) | 5 (10.2) | 5 (7.9) | 1 (3.8) | 0 | 1 (2.1) | 9 (9.8) | 13 (10.1) |

Note: *Significant at 0.05 level.

Abbreviations: GOLD, global Initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; % pred, percent predicted; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1...s; CAT, COPD assessment Test; mMRC, Modified Medical Research Council Scale.

This study found that patients grouped as A and B according to GOLD 2011 were categorized in the same way in GOLD 2017, but 31 of 47 (66%) patients in group C were reclassified as group A and 37 of 129 (28.7%) patients in group D were reclassified as group B in GOLD 2017. Thus, patients in a high-risk group (68/176; 39% of high-risk patients) were reclassified as low-risk in GOLD 2017, since they did not have frequent attacks and only had FEV1 values of below 50%. According to GOLD 2011, it is observed that the FEV1 values of the low-risk group in GOLD 2017 are lower and the high-risk group had a higher average number of exacerbations in the previous year. In GOLD 2017, while the proportional distribution of the groups other than category C came close to each other and category C had the lowest number of patients, at 6.4%.

Taiwan Obstructive Lung Disease (TOLD) study showed that up to 67% of patients in GOLD 2011 group C and D were reclassified to GOLD 2017 group A and B.13 A national cross-sectional survey in China indicated almost half of the old high-risk groups were regrouped to the new low-risk groups.12 Another study from Sweden found that 2017 GOLD reclassifies half of COPD subjects to lower-risk groups.15 According to the literature, almost half the patients formerly classified as ..úC..Ñ or ..úD..Ñ, solely based on poor lung function, shifted from the high-risk groups to the low-risk groups in GOLD 2017.13...18

In many studies, it was observed that category C was lower than the other groups according to the GOLD 2011 combined assessment proposal and this rate was reduced even more with the major revision in GOLD 2017.13,15,17,19,20 Furthermore, when using the assessment according to the GOLD 2017 report, publications are indicating that category C has dropped to 5% and below.13,15...17,20 Some studies have shown that group C proportion is between 6...14% according to GOLD 2017, similar to our results.14,18,21 These differences may be due to the country, center (tertiary hospital or primary health care, etc.) in which the study was conducted, or the methodology of the study (scales evaluating symptoms). Group C is expected to involve a small proportion of patients compared to other groups because a patient with frequent exacerbations is expected to have a high symptom score in clinical practice. However, some patients have poor dyspnea perception or restrict their physical activities to avoid dyspnea which may lead to their misclassification as group C instead of group D. This could explain why the acute exacerbation number of patients with Group C was similar to Group D despite having a low symptom score in our study. In the literature, researchers who were using only mMRC for symptom evaluation reported that as a limitation of their studies.14,16,20,21 The use of only one or other of CAT or mMRC scores in clinical practice may also lead to an incorrect assessment of patients... symptom status. We used both mMRC and CAT scores to assess the symptom status in our study. According to a recent study, 2% of the participants from the general population and 3% of the patient population were classi...ed as group C in GOLD 2017.16 A similar result was shown in the population-based PLATINO study of the GOLD 2011 classi...cation in which only 10 of 524 COPD patients (1,9%) were classi...ed in group C.20 Therefore some researchers argued that class C might be unnecessary.8,16,20 We also questioned whether to evaluate Group C and D as two separate groups in terms of the treatment recomendations with the GOLD 2019 revision.

The same treatment options are proposed for frequent exacerbators with or without high symptoms at follow-up independent of the COPD categories with GOLD 2019 revision.11 However different approaches are recommended as the initial treatment for Group C and D. Whereas some of the patients may be misclassified as group C because they perceive their symptoms incorrectly or are not evaluated in sufficient detail by their physician. It may be confusing in clinical practise that some options are presented in group D but are not recommended in group C. For instance, the blood eosinophil count or asthma history are not considered in the initial treatment of group C despite patients having frequent exacerbations. That is why we think that group C and D patients may be evaluated as a single group in terms of their treatment after GOLD 2019 revision.

The GOLD 2017 assessment led to changes in the distribution of patients... demography and clinical characteristics across categories used in previous studies. In GOLD 2017, patients of group C and D had a better pulmonary function but higher acute exacerbation rates, as well as a similar degree of dyspnea according to GOLD 2011. Group C and D had older patients and more patients with chronic bronchitis, coronary heart disease, and diabetes mellitus in GOLD 2017 than GOLD 2011. Pulmonary functions in the group A and B were worse in GOLD 2017.14 Another study demonstrated that the GOLD 2017 reclassified more patients into group A and B those with significantly worse lung function and higher BODE (Body mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise capacity) index compared with the GOLD 2011. In the comprehensive assessment of the GOLD 2017, group B and D may have greater disease severity and the differences between groups A and C were small.18 Similarly, the recent study indicated that group B has the same BODE index as group D, and both of them are signi...cantly higher than groups A and C in the GOLD 2017 reclassi...cation. The differences between groups (B versus D and A versus C) become smaller with this new approach thus decreasing the value of their separation.21 We observed in the GOLD 2017 the patients with poor pulmonary function and without frequent exacerbation in the previous year were shifted to the low-risk groups, so pulmonary function in the group A and B were worse and also group C and D had more exacerbations in our study as in the literature. In addition, we did not detect any difference between the groups according to GOLD 2011 and GOLD 2017 in terms of comorbidities and symptom status.

There are two limitations to our study. First, this study is cross-sectional so the exacerbation history of the patients was obtained from the statements of patients and hospital records. Second, the results may not reflect the general population because the patients were only recruited from a tertiary hospital and single-center.

ConclusionThe question is growing as to whether that group C in which the number of patients decreased even more after the major revision of GOLD 2017 is really necessary as a separate group. Furthermore the same treatment options are proposed to frequent exacerbators with or without high symptoms at follow-up with GOLD 2019 revision. On the other hand different approaches are recommended as the initial treatment for group C and D in this report. Some of the patients may be misclassified as group C because they have a poor perception of their symptoms and/or are not evaluated in sufficient detail by their physician. It may cause confusion in clinical practise that some options are presented in group D but are not recommended in group C despite latter having frequent exacerbations. We think that group C and D patients may be reclassified as a single group in clinical practise and prospective studies are needed in this context.

Authors contributionsEY: Study design, prepared the article, statistics, BY: study design, data collection; EYN: data collection, study design; MB: study design and prepared the article; SK: statistics

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.