Bullying has been described as repeated attempts to discredit, destabilize or instill fear in an intended target. Direct consequences can be emotional and psychological damage to self-worth, confidence and dignity, leading to psychological distress and discomfort that impact the overall progress of the victim in terms of professional growth and career progression.1

Medical settings are heavily affected by the phenomenon of bullying. Many reports from different geographic areas and settings have reported very frequencies of this phenomenon. A systematic review published in 2015 of fifty-seven cross-sectional studies and two cohort studies published in 2015 reported that 59.4% of medical trainees, globally, had experienced at least one form of bullying, harassment or discrimination.2 A recent scoping review including 68 studies and 82.389 respondents confirmed that bullying in academic medical settings is frequent, under-reported and has a huge impact on trainee's or young specialists’ well-being and professional path. The most common form of bullying was overwork and exclusion, and women tended to be victims more commonly. Men, senior consultants were the most common bullies.1

The recently published Wellcome's 2020 report, What Researchers Think about the Culture They Work In, shed light on the issue of bullying in research: 61% of respondents reported experiencing bullying or harassment, while 73% had witnessed it.3 Among the 4.267 researchers who completed the online survey (mostly from the UK), 30% were involved in biomedical science. Many reported that bullying and harassment are systematic and 33% of the leaders specifically often turned a blind eye to these behaviors.

Research in medical fields poses specific risks (and types) of bullying and mistreatment since this activity may interfere with medical specialty training, according to an old-fashioned, perverse mentality. The cornerstones of evidence-based medicine are clinical expertise, patient preference and research knowledge.4 Thus, modern physicians must have a solid background in all these aspects. Some may decide to advance in the career path becoming a clinician-scientist (usually in academia), namely those individuals holding an MD who perform biomedical research as their primary or co-primary professional activity.5

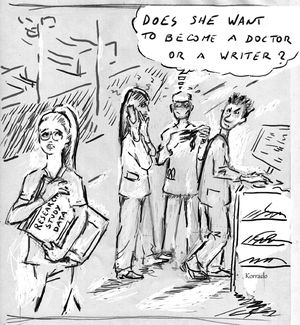

Physicians who work in both clinics and research know how much passion and dedication are needed to create, run, and publish research projects. Although this issue may be less important in centers with a long-lasting experience in research, those who like to do research may be prone to criticism, negative consequences or even bullying. This is even more important considering that most of those who decide to get experience in research are medical students, physicians during their residency, or young post-doc. An old-fashioned, toxic point of view considers only the quantity (often considering only the amount of time) during medical specialty training, while assuming scientific knowledge and research as deviations from the main path and primary goal. In this sense, an experienced (even good) physician who thinks like this can create a perverse vortex around him/her, including residents growing under this mentality. Clinician researchers and (good) academics are numerically fewer than clinicians focused only on clinical practice who do not participate in research. Thus, most of the specialty training is spent under their supervision. Young colleagues may easily become victims of these critiques since they need senior consultants as tutors for their practice. One of the effective advocacy strategies for “a successful bullying” is often like this: “Do you want to become a physician or a writer?” (Fig. 1). For these reasons, young colleagues enthusiastic about research may start to feel alone and frustrated. Sometimes, they can see deliberately created subtle obstacles to their scientific projects (i.e., data collections, inclusions in studies, assignment to interventions). This, in association with the time needed to improve scientific knowledge and writing skills, the stress linked to the projects while dealing with demanding duties in patient care, unstable career paths, and concerns about the work-life balance can easily lead to suddenly abandoning research. As the competition for faculty positions intensified in recent decades, early-career clinician-researchers came under the escalating pressure of expectations and of the publish or perish culture that dominates the professional lives of many researchers. Indeed, appropriate recognition is frequently not given to projects leaders of the hard work done in research projects (e.g., no authorship in papers). All these reasons may be the causes of the declining number of clinician-scientists during the last decades.6

The role of tutors and experienced colleagues is to support the professional progression of young colleagues, encouraging them to do research (when well considered) and learn from this . Those who decided to join research activities must be protected from eventual criticism, inquiries, refusal or other types of mistreatment by busy colleagues who were afraid of losing the right to say, ‘this is the way to do it because I have always done it this way’. Episodes of this type of bullying are not infrequent, are less investigated and must be condemned as a form of abuse. Prof. Umberto Veronesi, former Director of the European Institute of Oncology, top-class researcher, and a kind person used to say: “There is better care of patients where research is done”. This must be the mantra that inspires the current generation of physicians in training. For clinicians, research is an opportunity to be open-minded, to improve clinical skills, to apply the principles of evidence-based medicine in a better way. In brief, to be a better doctor.

Data on this type of bullying in medical research are lacking and must be specifically collected to have reliable estimates of this phenomenon and to evaluate potential associations with different settings and center characteristics. Supervisors, Directors, decision-makers, even in academia, must recognize and carefully monitor this phenomenon and the well-being of the next generation of clinician-researchers during their medical (and scientific) training promoting drivers for pursuing research as part of their clinical role and creating policies for a healthy and cooperative scientific community. Initiatives to develop a supportive framework for assisting early-career academics, making “skills of research” more accessible, promoting a cultural change focusing on the benefits of publishing and doing research during medical residency and the institution of mentorship programs, resident research award and scholarship and the provision of protected time for research may help demystify this type of bullying. As with other forms of bullying and mistreatment, the possibility of safe, anonymous reporting is the first step. Otherwise, the decline in clinician-scientists will continue and the evidence-based medicine principles will be at risk. We should avoid clinicians with interests in research feeling compelled to disgard this valuable combined skill set. We must change the culture of “not enough time for research” mentality. This form of bullying must not be normalized. More precisely, we must get rid of this form of bullying, which destroys the soul of medical science.

“To be honest, we all know that those who publish papers do not work or work less than those who work in the field… In the real training of a specialty physician, there is no time to do research or to write…”. We would like to thank the colleague who pronounced these words at the headquarter of a prestigious national scientific society, giving the authors the input for this manuscript. We would like to thank Dr. Antonio Corrado (“Korrado”) for providing the figure. The figure is authors' own.