Chronic respiratory diseases deteriorate sleep, impacting total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and sleep architecture.1 Nocturnal noninvasive ventilation (NIV) can restore sleep quality, as documented by polysomnography (PSG).1 Therefore, current guidelines stipulate that NIV should be initiated under PSG guidance.2 This is not done in practice because of resources limitation. Some evidence supports the hypothesis that, in the absence of PSG guidance, sleep quality can be poor under NIV.3 To further explore this hypothesis, we prospectively administered the Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI)4 to unselected patients placed under NIV without PSG guidance. In addition to prevalence data, we aimed to evaluate risk factors of poor sleep quality under NIV and to assess its impact on quality of life (QoL).

Over 90 days, we consecutively enrolled patients previously established on nocturnal home NIV without PSG guidance, clinically stable for at least 3 months and attending our NIV clinic for a scheduled follow-up. Study received ethics approval (CERNI, Rouen, E2018–06).

Patients answered the PSQI, the Severe Respiratory Insufficiency questionnaire (SRI; 0: poorest QoL; 100: best), and Epworth Sleepiness Scale. NIV side effects were graded from 0 –absent– to 4 –unbearable– according to an in-house questionnaire (eye irritation, rhinorrhea, dry mouth, hoarseness, bloating, mask or harness-related pain, pressure sores, leaks, deventilation dyspnea and perceived patient-ventilator asynchrony). NIV usage was assessed from 30-days ventilator logs. Leaks were considered abnormal if >2 L/min for Resmed® ventilators, >10 L/min for Philips Respironics® ventilators. A PSQI above 5 defined a “poor sleep quality group”,4 mirrored by a “good sleep quality” one.

Results are expressed as number and percentages, median and interquartile range (IQR). Mann-Whitney's U test, the chi-square test and Spearman's test were used for comparisons and correlations. Multivariate analysis (binomial logistic regression) incorporated clinically relevant variables with p <0.15 on univariate analysis. All tests were two-sided with 0.05 significance threshold (GraphPad Prism 6® and IBM SPSS® v26.0).

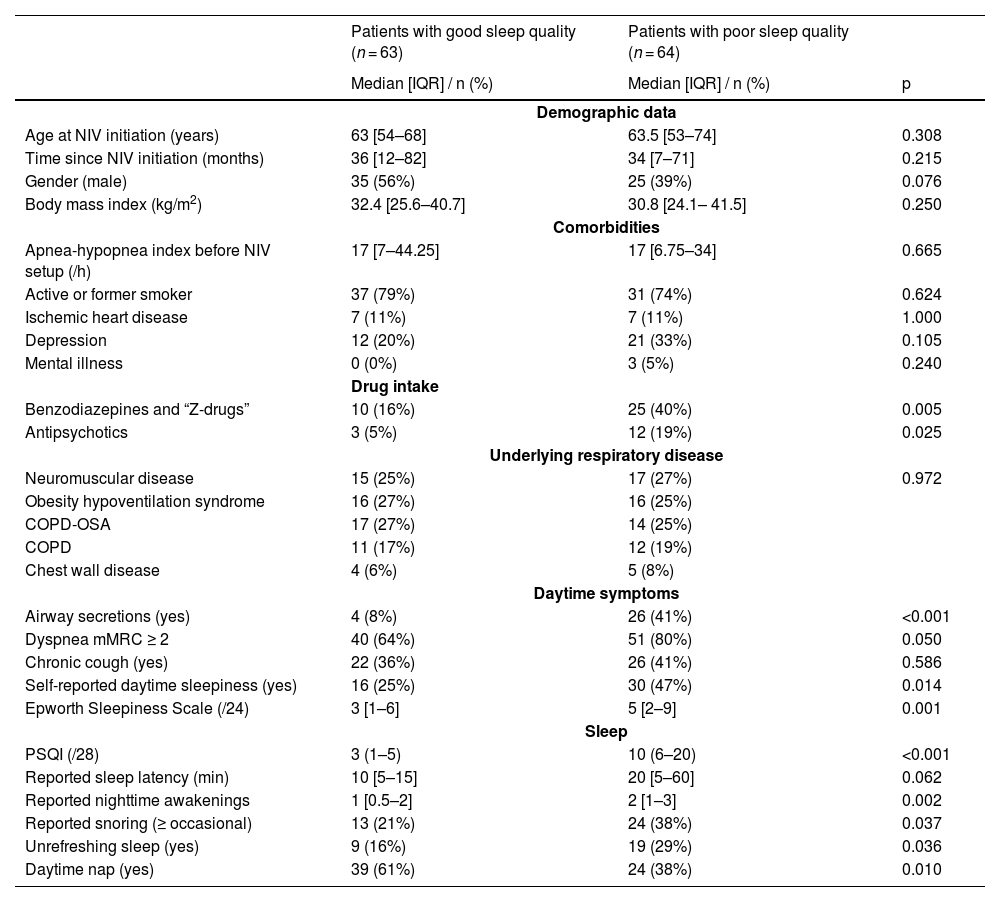

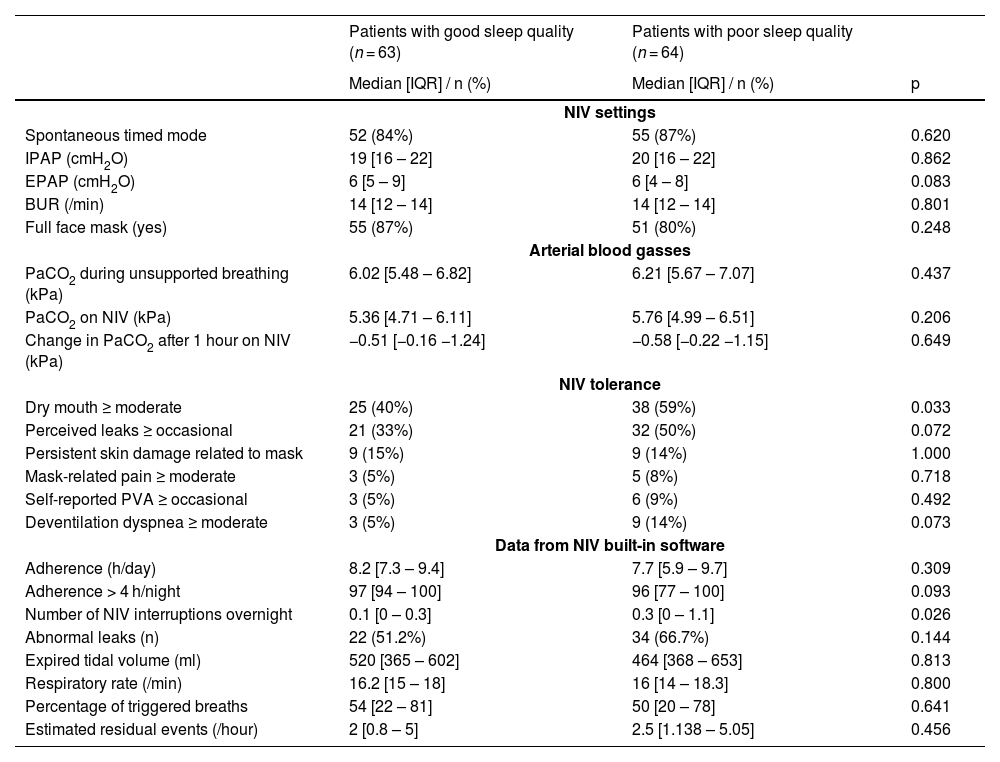

One hundred and fifty-nine patients attended the clinic during the study period; 32 declined to participate or could not be included (mostly because of staff unavailability), leaving 127 for analysis. The “poor sleep quality” group comprised 64 patients (50.5%) (Table 1). NIV indications, settings, effect on PaCO2 and adherence did not differ between groups (Table 2). Poor sleep quality patients more frequently reported grade 3–4 mouth dryness (59 vs 40% s, p = 0.033) and overnight NIV interruptions: 0.3 [0.0 – 1.1] breaks/night vs 0.1 [0.0 – 0.3], p = 0.026). Multivariate analysis evidenced 3 variables associated with poor sleep quality: benzodiazepine use (OR= 6.83 [1.53–30.65], p = 0.012), airway secretions (OR= 4.66 [1.06–20.43], p = 0.041), and abnormal leaks (OR= 4.52 [1.25–16.39], p = 0.022). SRI-evaluated QoL was lower in poor sleep quality patients (50.0 [39.7 – 62.5] vs. 62.0 [50.0 – 76.3] out of 100, p<0.001). PSQI inversely correlated with SRI (rho = −0.410, p < 0.001).

Clinical characteristics according to group (COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQR: interquartile range; mMRC: modified medical research council; OSA: obstructive sleep apnea; NIV: non-invasive ventilation; PSQI: Pittsburgh sleep quality index).

NIV settings, effect on PaCO2, tolerance, and data from built-in software according to group (BUR: back-up respiratory rate; EPAP: expiratory positive airway pressure; IQR: interquartile range; IPAP: inspiratory positive airway pressure; NIV: noninvasive ventilation; PaCO2: partial arterial pressure of carbon dioxide; PVA: patient-ventilator asynchrony).

Patients receiving benzodiazepines more often had a PSQI above 5 (71 vs. 41%, p = 0.004), had been on NIV for shorter durations (18 [4–50] months vs. 41 [12 – 83], p = 0.014), had poorer daytime PaCO2 control (6.39 [5.89 – 6.99] kPa vs. 6.09 [5.45 – 6.89], p = 0.038), and lower SRI scores (50 [38 – 64] vs. 59 [47 – 72], p = 0.030).

In this real-life study, half of a cohort of patients under long-term NIV initiated without PSG guidance reported poor sleep quality according to the PSQI, irrespective of NIV indication. This was associated with lower QoL, in line with literature.5

The three variables independently associated with poor sleep quality in this study can all be subject to medical intervention . Our data emphasize the known importance of controlling leaks during home nocturnal NIV. Indeed, leaks can fragment sleep and promote mouth dryness, as in our poor sleep quality group. Our observations also highlight the known importance of trying to control airway secretions in NIV patients (e.g., in-exsufflation in neuromuscular patients). Interestingly, 27% of our patients received benzodiazepines or “Z-drugs” that are contra-indicated in chronic respiratory failure where they heighten the risks of respiratory related hospitalization.6 They also increase upper airway resistance during sleep,7 which is deleterious during nocturnal NIV. NIV which may be inappropriately viewed as a “safety net” against deleterious effects of benzodiazepines on breathing control. We could not ascertain the motivation and timing of benzodiazepine prescriptions and causality between benzodiazepines and poor sleep quality cannot be inferred. Nevertheless, our observations call for a reminder that benzodiazepines are inadvisable in chronic respiratory insufficiency: their prescription in this context should systematically be questioned.

We acknowledge study limitations (single-center, observational design, lack of evaluation of the effect of NIV initiation on sleep quality) and the need for larger trials. However, we propose that evaluation of NIV efficacy should not be confined to currently recommended “hard” criteria (e.g. arterial carbon dioxide), but should incorporate the easy and costless evaluation of sleep quality (e.g. PSQI) and QoL (e.g. SRI) that should trigger more in-depth assessments.

Data availability statementThe data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors contributionJS, AC, IA, TS, MP: conception, acquisition, analysis, interpretation, drafting the work, revising critically.

RL, JM: acquisition, interpretation, revising critically.