The aim of this study is to investigate the effect of treatment modalities on survival among unoperat ed and locally-advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients aged 70 years and older, representing real-life data.

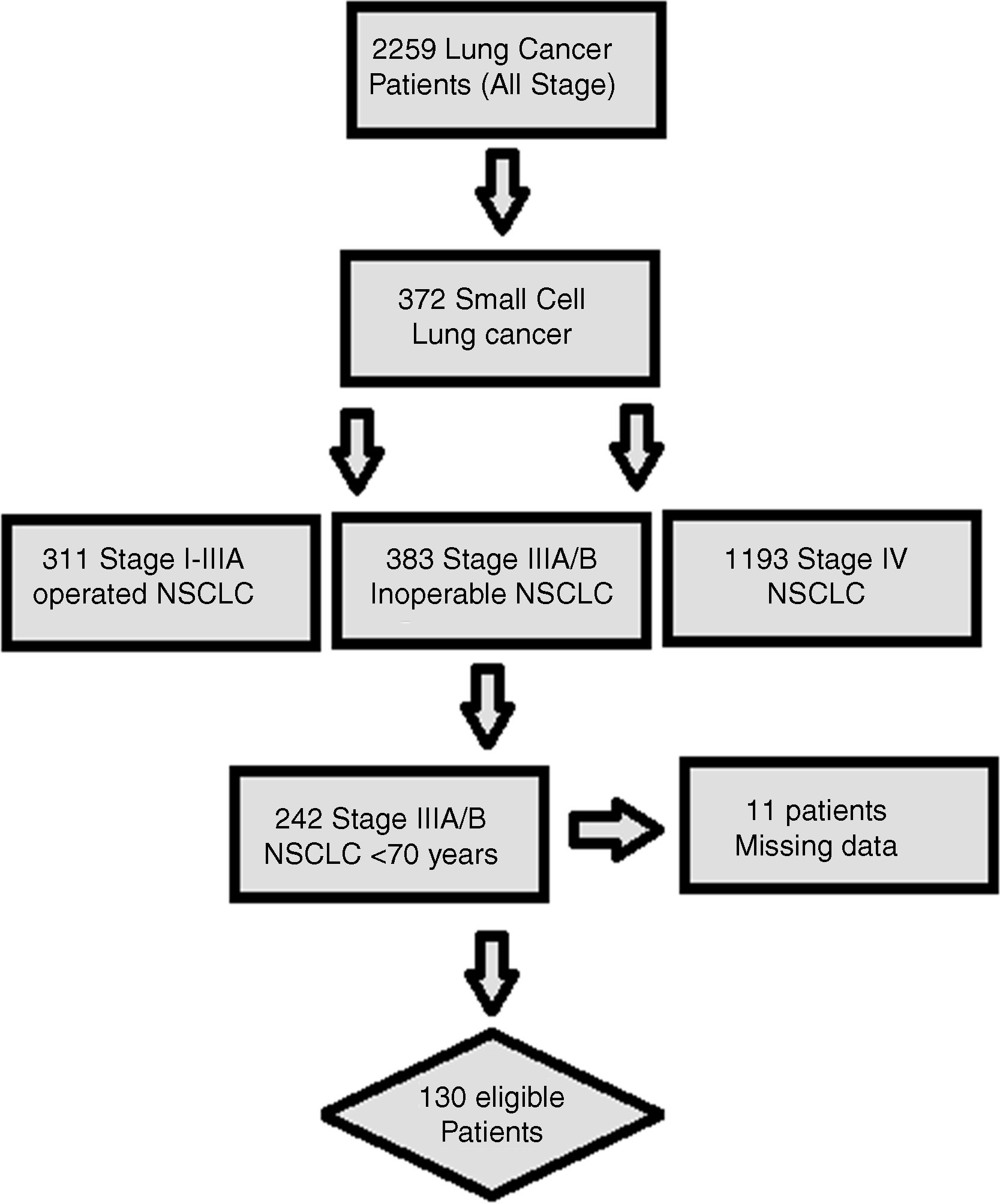

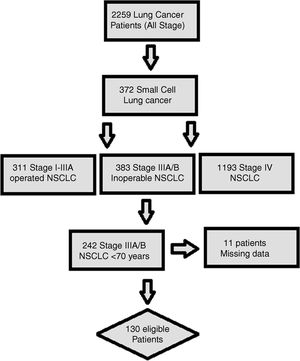

MethodsFrom 2005 through 2017, medical records of 2259 patients with lung cancer from Okmeydani Training and Research Hospital-Istanbul/Turkey were reviewed retrospectively. Patients with locally advanced NSCLC ≥ 70 years of age who did not undergo surgery for lung cancer were reviewed. In total, 130 patients were eligible for the final analysis. Patients were stratified into four groups as: chemotherapy (CT), concurrent chemoradiotherapy (cCRT), sequential chemoradiotherapy (sCRT), and radiotherapy (RT) only.

ResultsOf the 130 patients included in the analysis; CT, cCRT, sCRT, and RT only were applied to 25(19.2%), 30(23.1%), 31(23.8%), and 44(33.8%) patients, retrospectively. Twelve (9.2%) patients were female. Median age was 72 years (range, 70–88). Sixty (46.2%) patients had stage IIIA disease and 70(53.8%) patients had stage IIIB disease. Median progression-free survival(mPFS) in patients treated with CT, cCRT, sCRT, and RT were 8.0, 15, 10, and 9.0 months, respectively(p = 0.07). Corresponding median overall survival (mOS) were 10, 33, 20, and 15 months (p = 0.04). In multivariate analysis, stage IIIB disease [hazard ratio (HR), 2.8], ECOG-PS 2(HR, 2.10), and ECOG-PS 3–4(HR, 5.13) were found to be the negative factors affecting survival, while cCRT (HR, 0.45) and sCRT (HR, 0.50) were the independent factors associated with better survival.

ConclusionThis study showed that the use of combined treatment modality was associated with better survival in elderly patients with locally advanced NSCLC, with the greatest survival observed in patients treated with cCRT. We therefore suggest that cCRT, when feasible, should be strongly considered in locally advanced NSCLC patients 70 years and over.

Lung cancer (LC) is the most common cancer in the world, causing a large number of cancer-related deaths. In 2012, approximately 1.8 million patients had LC worldwide, with an estimated 1.6 million deaths in the same year. About 95% of all LC cases are classified as small cell lung cancer (SCLC) or non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1,2

The treatment plan in LC depends on several factors such as cell type (e.g. SCLC, NSCLC), patient medical condition, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS), and tumor stage. Surgery, chemotherapy (CT), radiotherapy (RT), or chemoradiotherapy (CRT) are widely used to treat patients with a curative intent in stage I, II, or III NSCLC.2,3

Stage III NSCLC involves a very heterogeneous group of patients. In addition, many aspects of treatment in stage III disease are still controversial. The definition of stage III disease in LC has changed over time. Moreover, many improvements in LC treatment, including the use of new CT agents, recent advances in RT, and new surgical techniques, limit the interpretation of the results from previous clinical trials.3–5

Indeed, LC is an elderly population disease. The median age at diagnosis in LC is 71. Therefore, it becomes increasingly important to establish an effective treatment for elderly patients with LC. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy (cCRT) is the mainstay of treatment for patients with locally advanced and inoperable NSCLC. However, few clinical studies have been designed to specifically examine the treatment outcomes of elderly patients with stage III NSCLC and it is unclear whether cCRT is appropriate for elderly patients.6,7

This was a real-world study and aimed to analyze the factors affecting survival along with the effects of different treatment modalities (CT, sCRT, cCRT, and RT) on treatment outcomes in unoperated and locally-advanced NSCLC patients aged 70 years and older.

MethodsStudy populationHospital records and written archive files of 2259 patients with LC, who were followed up and treated between 2005 and 2017 in Okmeydanı Training and Research Hospital-Istanbul, Turkey, were reviewed retrospectively. Patients with a second primary malignancy, age <70 years, those with missing data, metastatic disease at diagnosis, and patients undergoing surgery for LC were excluded from the study. In total, 130 locally advanced (clinical stage IIIA-IIIB) and unoperated NSCLC patients aged 70 and over were subtracted for the analysis (Fig. 1). The staging procedure was performed by using 18F-FDG-Positron emission tomography/computed tomography and brain magnetic resonance imaging before the treatment. Patients were restaged according to the AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) Cancer Staging Manual, 8th edition.

Data collectionClinical and demographic features including age, gender, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), presence of comorbid disease (e.g. hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease), ECOG-PS, histological subtype, recurrence, treatment modality, CT regimen, response to treatment, first-line CT regimen used in the metastatic setting, and data regarding the patient final status were obtained from written archive files. According to the treatment modality, patients were divided into four groups as CT, cCRT, sequential chemoradiotherapy (sCRT), and RT only. In patients receiving RT (cCRT, sCRT, and RT), RT was administered at a total dose of 60−66 Gy, 2 Gy/day per fraction.

Treatment modalities and CT regimens were described as follows; *CT, single-agent platinum (carboplatin or cisplatin) or combined cytotoxic CT, *cCRT; carboplatin (AUC 2) + paclitaxel (50 mg/m2 iv, on day 1 weekly) + concurrent thoracic RT, or cisplatin (75 mg/m2 iv, on day 1 and 8) + etoposide (100 mg/m2 iv, on day 1–5 ), cycled every 28 days + concurrent thoracic RT, or cisplatin (20 mg/m2 iv, on day 1 weekly) + docetaxel (20 mg/m2 iv, on day 1 weekly) + concurrent thoracic RT, *sCRT; single-agent platinum (carboplatin or cisplatin) or combined cytotoxic CT was delivered within 30 days before or after initiation of RT.

BMI was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by height in meters squared (kg/m2). Progression free survival (PFS) was calculated as the time interval from the beginning of treatment to the date of progression. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time period from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last alive contact.

Ethical approvalThis study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Okmeydani Training and Research Hospital, University of Health Sciences (48670771-514.10).

Statistical analysisStatistical Package for Social Sciences 22.0 for Windows software (Armonk NY, IBM Corp. 2013) was used for statistical analysis. For numerical variables, descriptive statistics were reported as mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum. For categorical variables, descriptive statistics were presented as number and percentage. Student's t-test was used when numerical variable provided a normal distribution condition between the two independent groups and Mann Whitney U test was used when the normal distribution condition was not met. Chi square analysis was used to compare the ratios among the groups. Monte Carlo simulation was applied when the conditions were not met. Survival was analyzed using Kaplan Meier method. The determinant factors were examined by Cox Regression Analysis. Forward stepwise model was used for values <0.150 in univariate analysis. Statistical significance level was accepted as p < 0.05.

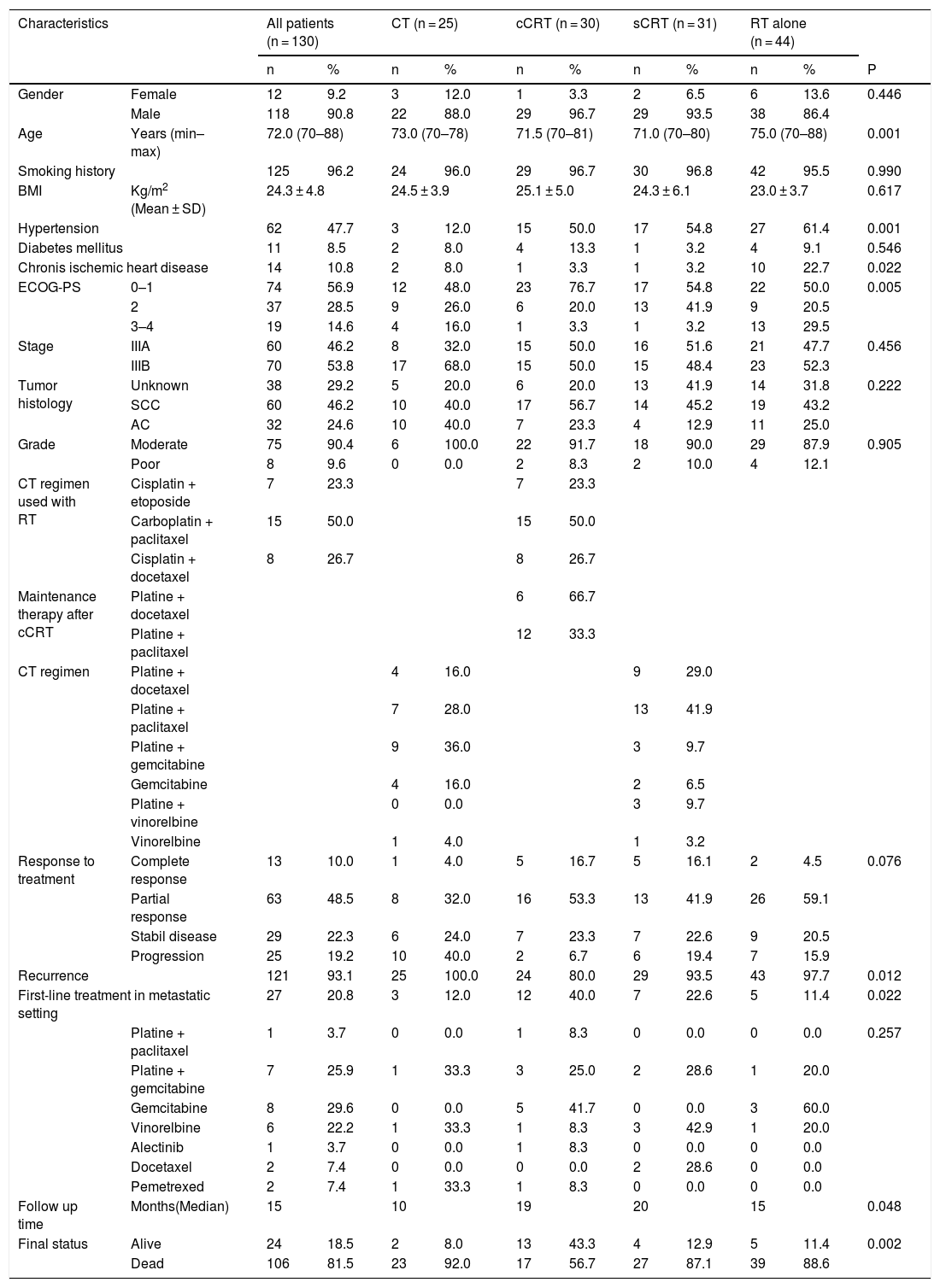

ResultsOf the 130 patients included in the analysis; CT, cCRT, sCRT, and RT were applied in 25 (19.2%), 30 (23.1%), 31 (23.8%), and 44 (33.8%) patients, retrospectively. Twelve (9.2%) patients were female and 118 (90.8%) patients were male, with a median age of 72 years (range, 70–88). A total of 125 (96.2%) patients had smoking history. Nearly half of the patients (47.7%) had HT at the time of diagnosis. The information of histological subtype in 38 (29.2%) patients was not available. Sixty (46.2%) patients were stage IIIA and 70 (53.8%) patients were stage IIIB. During the follow-up, 106 (81.5%) patients died and 121 patients experienced disease recurrence, of the patients who developed recurrence, only 27 (20.8%) were able to receive first-line CT (Table 1).

Patient data.

| Characteristics | All patients (n = 130) | CT (n = 25) | cCRT (n = 30) | sCRT (n = 31) | RT alone (n = 44) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | P | ||

| Gender | Female | 12 | 9.2 | 3 | 12.0 | 1 | 3.3 | 2 | 6.5 | 6 | 13.6 | 0.446 |

| Male | 118 | 90.8 | 22 | 88.0 | 29 | 96.7 | 29 | 93.5 | 38 | 86.4 | ||

| Age | Years (min–max) | 72.0 (70–88) | 73.0 (70–78) | 71.5 (70–81) | 71.0 (70–80) | 75.0 (70–88) | 0.001 | |||||

| Smoking history | 125 | 96.2 | 24 | 96.0 | 29 | 96.7 | 30 | 96.8 | 42 | 95.5 | 0.990 | |

| BMI | Kg/m2 (Mean ± SD) | 24.3 ± 4.8 | 24.5 ± 3.9 | 25.1 ± 5.0 | 24.3 ± 6.1 | 23.0 ± 3.7 | 0.617 | |||||

| Hypertension | 62 | 47.7 | 3 | 12.0 | 15 | 50.0 | 17 | 54.8 | 27 | 61.4 | 0.001 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 | 8.5 | 2 | 8.0 | 4 | 13.3 | 1 | 3.2 | 4 | 9.1 | 0.546 | |

| Chronis ischemic heart disease | 14 | 10.8 | 2 | 8.0 | 1 | 3.3 | 1 | 3.2 | 10 | 22.7 | 0.022 | |

| ECOG-PS | 0–1 | 74 | 56.9 | 12 | 48.0 | 23 | 76.7 | 17 | 54.8 | 22 | 50.0 | 0.005 |

| 2 | 37 | 28.5 | 9 | 26.0 | 6 | 20.0 | 13 | 41.9 | 9 | 20.5 | ||

| 3–4 | 19 | 14.6 | 4 | 16.0 | 1 | 3.3 | 1 | 3.2 | 13 | 29.5 | ||

| Stage | IIIA | 60 | 46.2 | 8 | 32.0 | 15 | 50.0 | 16 | 51.6 | 21 | 47.7 | 0.456 |

| IIIB | 70 | 53.8 | 17 | 68.0 | 15 | 50.0 | 15 | 48.4 | 23 | 52.3 | ||

| Tumor histology | Unknown | 38 | 29.2 | 5 | 20.0 | 6 | 20.0 | 13 | 41.9 | 14 | 31.8 | 0.222 |

| SCC | 60 | 46.2 | 10 | 40.0 | 17 | 56.7 | 14 | 45.2 | 19 | 43.2 | ||

| AC | 32 | 24.6 | 10 | 40.0 | 7 | 23.3 | 4 | 12.9 | 11 | 25.0 | ||

| Grade | Moderate | 75 | 90.4 | 6 | 100.0 | 22 | 91.7 | 18 | 90.0 | 29 | 87.9 | 0.905 |

| Poor | 8 | 9.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 8.3 | 2 | 10.0 | 4 | 12.1 | ||

| CT regimen used with RT | Cisplatin + etoposide | 7 | 23.3 | 7 | 23.3 | |||||||

| Carboplatin + paclitaxel | 15 | 50.0 | 15 | 50.0 | ||||||||

| Cisplatin + docetaxel | 8 | 26.7 | 8 | 26.7 | ||||||||

| Maintenance therapy after cCRT | Platine + docetaxel | 6 | 66.7 | |||||||||

| Platine + paclitaxel | 12 | 33.3 | ||||||||||

| CT regimen | Platine + docetaxel | 4 | 16.0 | 9 | 29.0 | |||||||

| Platine + paclitaxel | 7 | 28.0 | 13 | 41.9 | ||||||||

| Platine + gemcitabine | 9 | 36.0 | 3 | 9.7 | ||||||||

| Gemcitabine | 4 | 16.0 | 2 | 6.5 | ||||||||

| Platine + vinorelbine | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 9.7 | ||||||||

| Vinorelbine | 1 | 4.0 | 1 | 3.2 | ||||||||

| Response to treatment | Complete response | 13 | 10.0 | 1 | 4.0 | 5 | 16.7 | 5 | 16.1 | 2 | 4.5 | 0.076 |

| Partial response | 63 | 48.5 | 8 | 32.0 | 16 | 53.3 | 13 | 41.9 | 26 | 59.1 | ||

| Stabil disease | 29 | 22.3 | 6 | 24.0 | 7 | 23.3 | 7 | 22.6 | 9 | 20.5 | ||

| Progression | 25 | 19.2 | 10 | 40.0 | 2 | 6.7 | 6 | 19.4 | 7 | 15.9 | ||

| Recurrence | 121 | 93.1 | 25 | 100.0 | 24 | 80.0 | 29 | 93.5 | 43 | 97.7 | 0.012 | |

| First-line treatment in metastatic setting | 27 | 20.8 | 3 | 12.0 | 12 | 40.0 | 7 | 22.6 | 5 | 11.4 | 0.022 | |

| Platine + paclitaxel | 1 | 3.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 8.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.257 | |

| Platine + gemcitabine | 7 | 25.9 | 1 | 33.3 | 3 | 25.0 | 2 | 28.6 | 1 | 20.0 | ||

| Gemcitabine | 8 | 29.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 41.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 60.0 | ||

| Vinorelbine | 6 | 22.2 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 8.3 | 3 | 42.9 | 1 | 20.0 | ||

| Alectinib | 1 | 3.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 8.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Docetaxel | 2 | 7.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 28.6 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Pemetrexed | 2 | 7.4 | 1 | 33.3 | 1 | 8.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Follow up time | Months(Median) | 15 | 10 | 19 | 20 | 15 | 0.048 | |||||

| Final status | Alive | 24 | 18.5 | 2 | 8.0 | 13 | 43.3 | 4 | 12.9 | 5 | 11.4 | 0.002 |

| Dead | 106 | 81.5 | 23 | 92.0 | 17 | 56.7 | 27 | 87.1 | 39 | 88.6 | ||

Abbreviations: AC, Adenocarcinoma; ECOG-PS, Eastern cooperative oncology group performance status; CT, Chemotherapy; cCRT, Concurrent chemoradiotherapy; RT, Radiotherapy; SCC, Squamous cell carcinoma; sCRT: Sequential chemoradiotherapy; BMI, body mass index.

In patients receiving cCRT, radiotherapy was administered concurrently with cisplatin + etoposide (CE) in 7 (23.3%) patients, carboplatin + paclitaxel (CP) in 15 (50%) patients, and cisplatin + docetaxel (CD) in 8 (26.7) patients. In total, 18 patients received a consolidation CT following cCRT; 12 of 15 patients receiving cCRT with CP received 2 more cycles of carboplatin (AUC 5–6 iv, on day 1) + paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, on day 1), cycled every 21 days and 6 of 8 patients receiving cCRT with CD received 2 more cycles of cisplatin (75 mg/m2 iv, on day 1) + docetaxel (75 mg/m2 iv, on day 1), cycled every 21 days (Table 1).

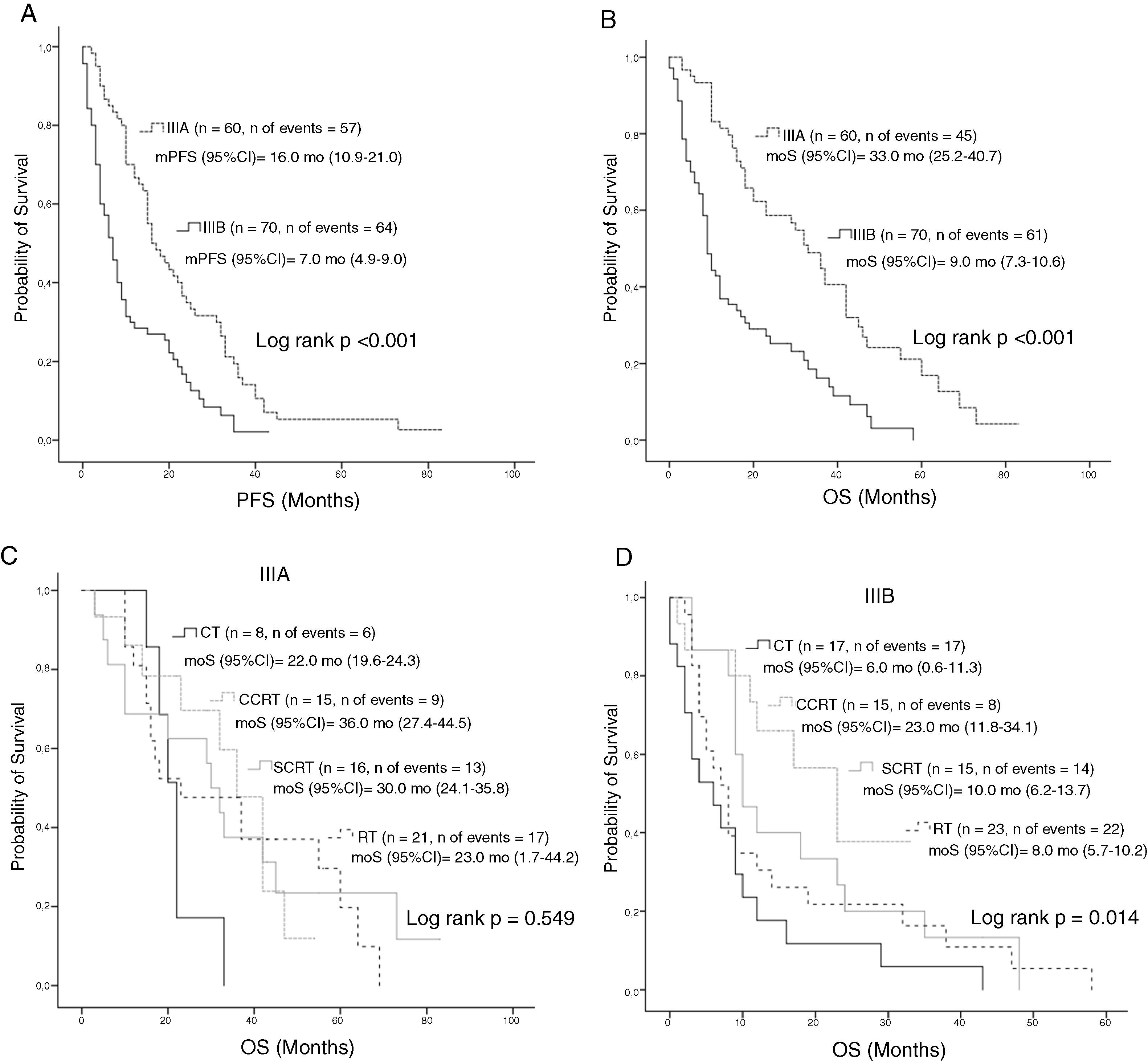

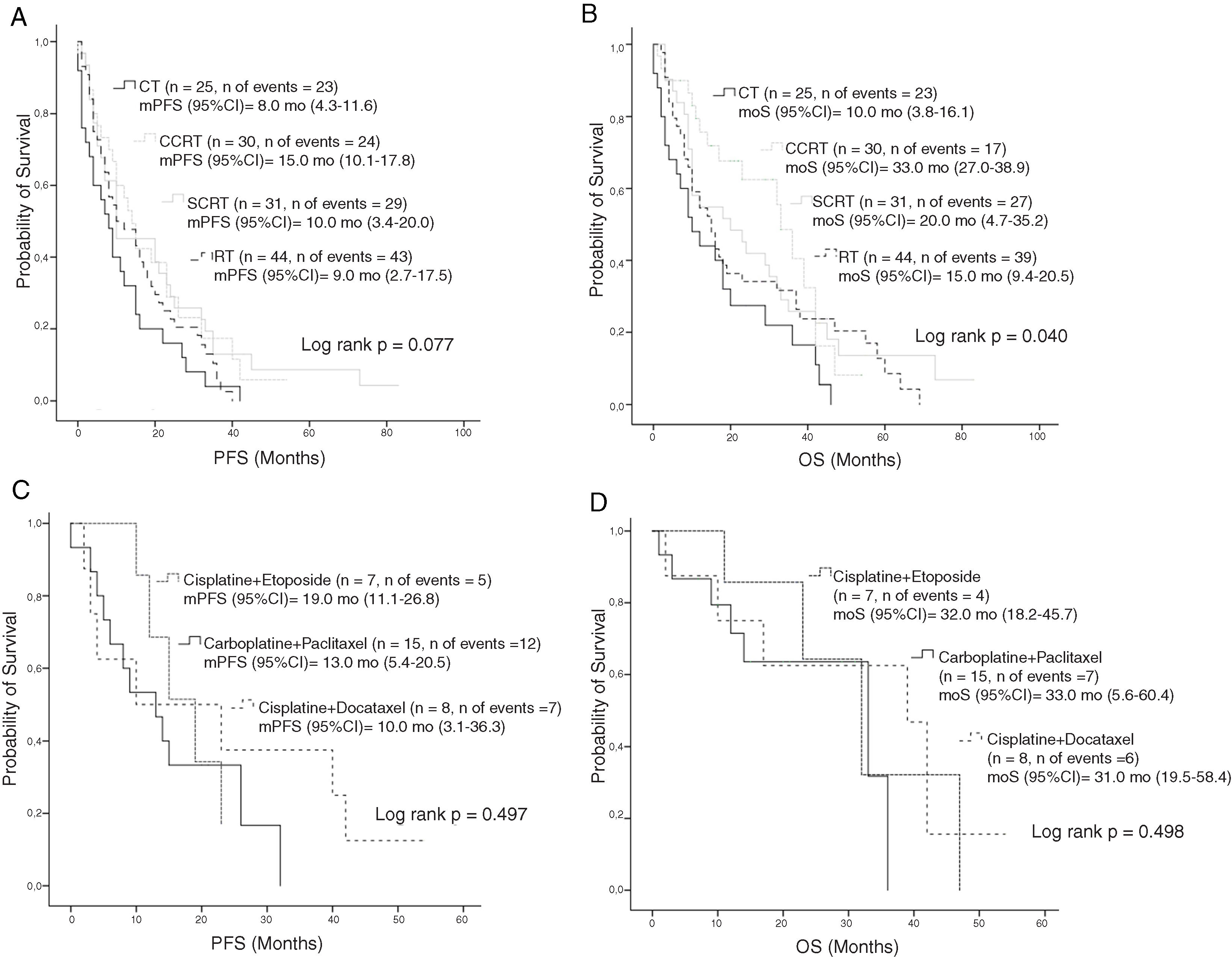

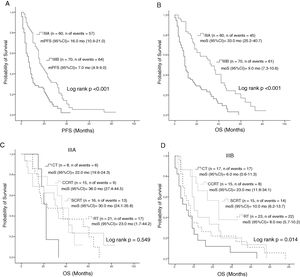

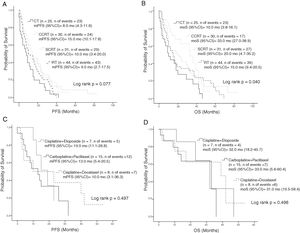

Median PFS and mOS durations according to the disease stage were 16 and 33 months in patients with stage IIIA disease versus 7.0 and 9.0 months in those with stage IIIB, respectively (log rank p < 0.001, log rank p < 0.001, respectively). Stage IIIA patients treated with CT, cCRT, sCRT, or RT alone had mOS of 22, 36, 30, and 23.0 months, respectively (Log rank p = 0.549). Corresponding mOS durations in stage IIIB were 6, 23, 10, and 8.0 months (Log rank p = 0.014) (Fig. 2). Median PFS in all patients treated with CT, cCRT, sCRT, and RT alone were 8, 15, 10, and 9 months, respectively (Log rank p = 0.077). Corresponding mOS durations were 10, 33, 20, and 15 months (Log rank p = 0.04). No significant differences were observed in mOS and mPFS between the CT regimens given concurrently with RT (Log rank p = 0.497, Log rank p = 0.498, respectively) (Fig. 3).

Survival according to stage; A, PFS according to stage; B, OS according to stage; C, OS according to treatment groups in stage IIIA; D, OS according to treatment groups in stage IIIB.

Abbreviations: CT, Chemotherapy; cCRT, Concurrent chemoradiotherapy; OS, Overall survival; RT, Radiotherapy; PFS, Progression-free survival: sCRT, Sequential chemoradiotherapy.

OS according to the treatment; A, PFS according to the treatment modality; B, OS according to the treatment modality; C, PFS according to the CT regimen in patients treated with cCRT; D, OS according to the CT regimen in patients treated with cCRT.

Abbreviations: CT, Chemotherapy; cCRT, Concurrent chemoradiotherapy; OS, Overall survival; RT, Radiotherapy; PFS, Progression-free survival: sCRT, Sequential chemoradiotherapy.

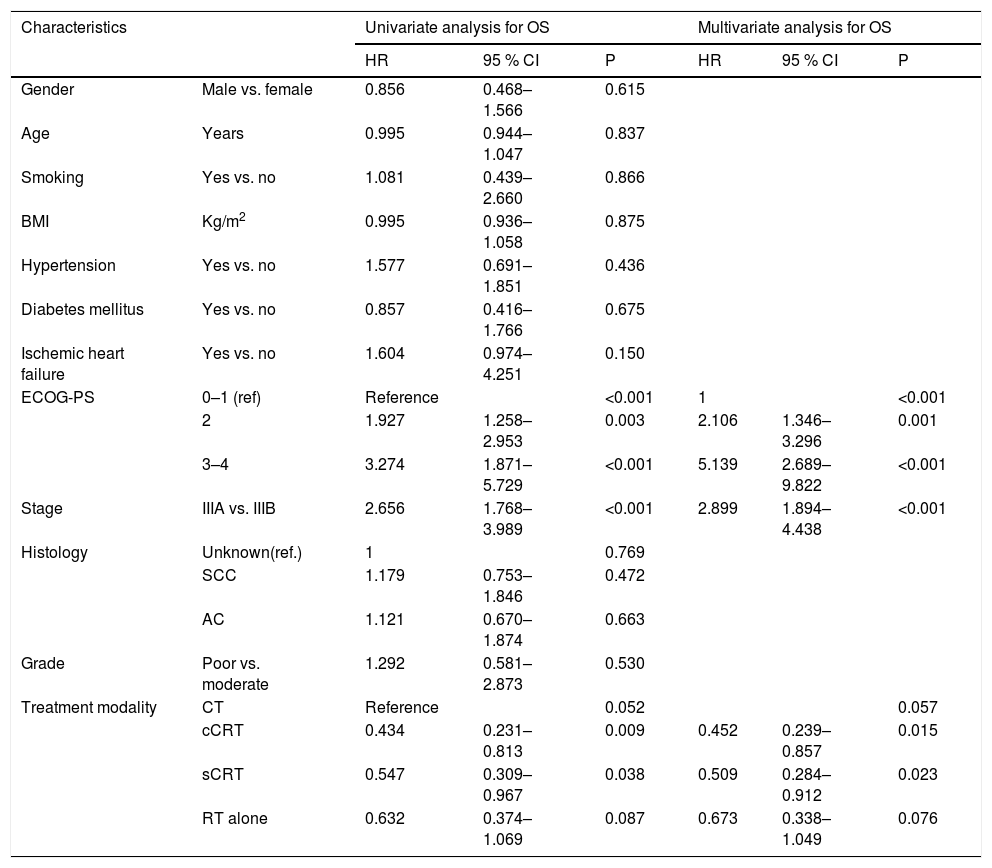

In univariate analysis, ECOG-PS 2 [hazard ratio (HR), 1.927; 95% Confidence interval (CI), 1.258–2.953], ECOG-PS 3–4 (HR, 3.274; 95% CI, 1.874–5.729), and stage IIIB disease (HR, 2.656; 95% CI, 1.768–3.989) were the factors adversely affecting survival, whereas cCRT and sCRT (HR, 0.434; 95% CI, 0.231–0.813 and HR, 0.547; 95% CI, 0.309–0.967) were observed to be associated with favorable survival. Likewise, In multivariate analysis, stage IIIB disease (HR,2.899; 95% CI,1.894–4.438), ECOG-PS 2 (HR, 2.106; 95 % CI, 1.346–3.296), and ECOG-PS 3–4 (HR,5.139; 95%CI, 2.689–9.822) were found to be the negative factors affecting survival, while cCRT and sCRT were the independent factors associated with better survival (HR, 0.452; 95% CI, 0.239-0.857 and HR, 0.509; 95% CI, 0.284-0.912, respectively) (Table 2)

Factors affecting survival.

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis for OS | Multivariate analysis for OS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95 % CI | P | HR | 95 % CI | P | ||

| Gender | Male vs. female | 0.856 | 0.468–1.566 | 0.615 | |||

| Age | Years | 0.995 | 0.944–1.047 | 0.837 | |||

| Smoking | Yes vs. no | 1.081 | 0.439–2.660 | 0.866 | |||

| BMI | Kg/m2 | 0.995 | 0.936–1.058 | 0.875 | |||

| Hypertension | Yes vs. no | 1.577 | 0.691–1.851 | 0.436 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | Yes vs. no | 0.857 | 0.416–1.766 | 0.675 | |||

| Ischemic heart failure | Yes vs. no | 1.604 | 0.974–4.251 | 0.150 | |||

| ECOG-PS | 0–1 (ref) | Reference | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 | ||

| 2 | 1.927 | 1.258–2.953 | 0.003 | 2.106 | 1.346–3.296 | 0.001 | |

| 3–4 | 3.274 | 1.871–5.729 | <0.001 | 5.139 | 2.689–9.822 | <0.001 | |

| Stage | IIIA vs. IIIB | 2.656 | 1.768–3.989 | <0.001 | 2.899 | 1.894–4.438 | <0.001 |

| Histology | Unknown(ref.) | 1 | 0.769 | ||||

| SCC | 1.179 | 0.753–1.846 | 0.472 | ||||

| AC | 1.121 | 0.670–1.874 | 0.663 | ||||

| Grade | Poor vs. moderate | 1.292 | 0.581–2.873 | 0.530 | |||

| Treatment modality | CT | Reference | 0.052 | 0.057 | |||

| cCRT | 0.434 | 0.231–0.813 | 0.009 | 0.452 | 0.239–0.857 | 0.015 | |

| sCRT | 0.547 | 0.309–0.967 | 0.038 | 0.509 | 0.284–0.912 | 0.023 | |

| RT alone | 0.632 | 0.374–1.069 | 0.087 | 0.673 | 0.338–1.049 | 0.076 | |

Abbreviations: AC, Adenocarcinoma; ECOG PS, Eastern cooperative oncology group performance status; CT, Chemotherapy; cCRT, Concurrent chemoradiotherapy; RT, Radiotherapy; SCC, Squamous cell carcinoma; sCRT: Sequential chemoradiotherapy.

It is known that the feasibility rates of definitive treatment in elderly patients with locally advanced NSCLC are lower than those of non-elderly patients.8 In this study, we investigated the factors affecting survival in stage III NSCLC patients aged 70 years and older who were treated with CT, cCRT, sCRT, or RT alone. We showed that survival was significantly decreased as ECOG-PS increased. However, the use of combined treatment modality significantly increased survival, with the best outcomes observed in patients treated with cCRT.

NSCLC accounts for approximately 85% of all cases of LC. In spite of the progress achieved in treatment modalities, NSCLC still has a poor prognosis. Age, gender, histology, and stage are known prognostic factors and new biological markers are being investigated.9 Stage III NSCLC represents approximately 30% of newly-diagnosed cancer patients and this patient population is extremely heterogeneous, hence requiring a multidisciplinary treatment approach. Elderly patients with LC account for more than one third of all LC patients However, limited data is currently available to guide decision-making in the elderly population. Given the conflicting and inadequate data on this patient population, the optimal treatment strategy for elderly patient with stage III NSCLC needs to be further defined.10–13

Driessen et al. performed a multicenter retrospective study including 216 stage III NSCLC patients and reported mOS to be 18 months for patients treated with cCRT, 12 months for those receiving sCRT, 11 months for patients treated with RT alone, and 5 months for patients not undergoing a curative treatment. The authors also concluded that there was no improvement in OS in patients aged 70 and over treated with cCRT, compared with patients receiving sCRT or RT alone.14 On the contrary, in the study by Davidoff et al. using Survival Epidemiology and End Results-Medicare, stage IIIA and IIIB patients over 65 years of age treated with cCRT had significantly improved overall survival rates. In addition, stage and ECOG-PS were found to be independent factors affecting survival.15 Similarly, in a subgroup analysis of 2 prospective studies by Schild et al. analyzing 166 patients with NSCLC aged 65 and over, mOS was 10.5 months in patients receiving RT alone and 13.7 months in those treated with cCRT, demonstrating a significantly longer survival with cCRT.16 Additionally, in a multicenter and prospective study by Atagi et al. including 200 patients with stage IIIA-IIIB NSCLC treated with either RT alone (n = 100) or cCRT (n = 100), mOS was found to be 16.9 in patients receiving RT alone versus 22.4 months in those treated with cCRT, with a statistically significant survival difference.17 Our results were similar to those reported by Atagi et al., with corresponding OS durations of 15 and 33 months. Moreover, in our study, stage, ECOG-PS, and receiving cCRT were found to be independent factors affecting survival, as shown by Atagi et al.

In the phase-II SWOG-9019 study, 50 patients with stage IIIB NSCLC received cCRT with CE and demonstrated a mOS of 15 months.18 In a later phase III study, mOS was detected 23.2 months and it was shown that maintenance treatment with docetaxel following cCRT with CE had no survival advantage.19 In another phase II study by Belani et al. who analyzed inoperable and locally advanced NSCLC patients, 2 cycles of additional CP were given after cCRT with CP and mOS was found to be 16 months.20 In a later phase III 3 study comparing the cCRT with CE vs. cCRT with CP, mOS was found to be 23.3 months and 20.7 months, respectively.21 Yamamoto et al. and Kiura et al. reported mOS of 23.1 and 23.4 months, respectively, in locally advanced and inoperable NSCLC patients treated with cCRT with CD.22,23 Our study also included stage IIIA NSCLC patients and no maintenance CT was given after cCRT with CE, whereas most patients treated with cCRT with CP and cCRT with CD received maintenance CT. In our study, although patients receiving cCRT with CE had the best survival durations, there was no statistically significant difference in mOS duration between the CT regimens given concurrently with RT.

Compared with the previous studies, the treatment groups in our study were more homogeneous and the follow up period was relatively longer.14–16 In addition, survival analysis could be performed according to the treatment regimens concurrently used with RT. Although real life data were presented in this study, this was a single-centered study of a retrospective nature, including a relatively small number of cases. The results of this study may therefore be flawed by selection bias inherent in retrospective studies. Another major limitation for this study was the failure to reach the side effect profile in the entire population. In addition, a detailed geriatric evaluation could not be performed.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that ECOG-PS and CRT were found to be the most important factors affecting survival in locally advanced and unoperated stage III NSCL patients aged 70 years and over. The best survival was achieved in patients treated with cCRT. In light of these data, we think that cCRT should be strongly considered in elderly patients with locally advanced NSCLC, taking into account the performance status and comorbidities in the elderly population. Nevertheless, our results need to be confirmed by larger prospective studies.

Author contributionsConcept – AS, SC, SS; Design – NY, CG, SS; Supervision – SC, SS, CD, AS; Resources – CG, SC, SA; Materials – AS, NY, SA, CG; Data Collection and/or Processing – AS, NY FA,CD; Analysis and/or Interpretation – SC, FA, AS; Literature Search – CD, AS, FA, SS; Writing Manuscript – AS,SS; Critical Review – SC,CD, FA; Other – CG, FA, SC, NY.

Informed consent statementPatients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous clinical data, which were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment by written consent.

Funding sourceNone.

Conflict-of-interest statementAll authors declare no conflicts-of-interest related to this article.