According to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), the levels of asthma symptom control can be divided into controlled, partially controlled and uncontrolled asthma. Optional therapy for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)-hypersensitive asthmatics uses aspirin desensitization, but until now, this therapy is not established in difficult to treat cases. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of aspirin desensitization in patients with poorly controlled asthma.

MethodsPatients with poorly controlled asthma, NDAIDs hypersensitivity and aspirin desensitization were included in the retrospective study. The data were compared to those obtained from patients with controlled asthma and aspirin therapy. Lung function, levels of asthma symptom control, asthma medication, the size of nasal polyps (NP) and smell function were evaluated over 18 months.

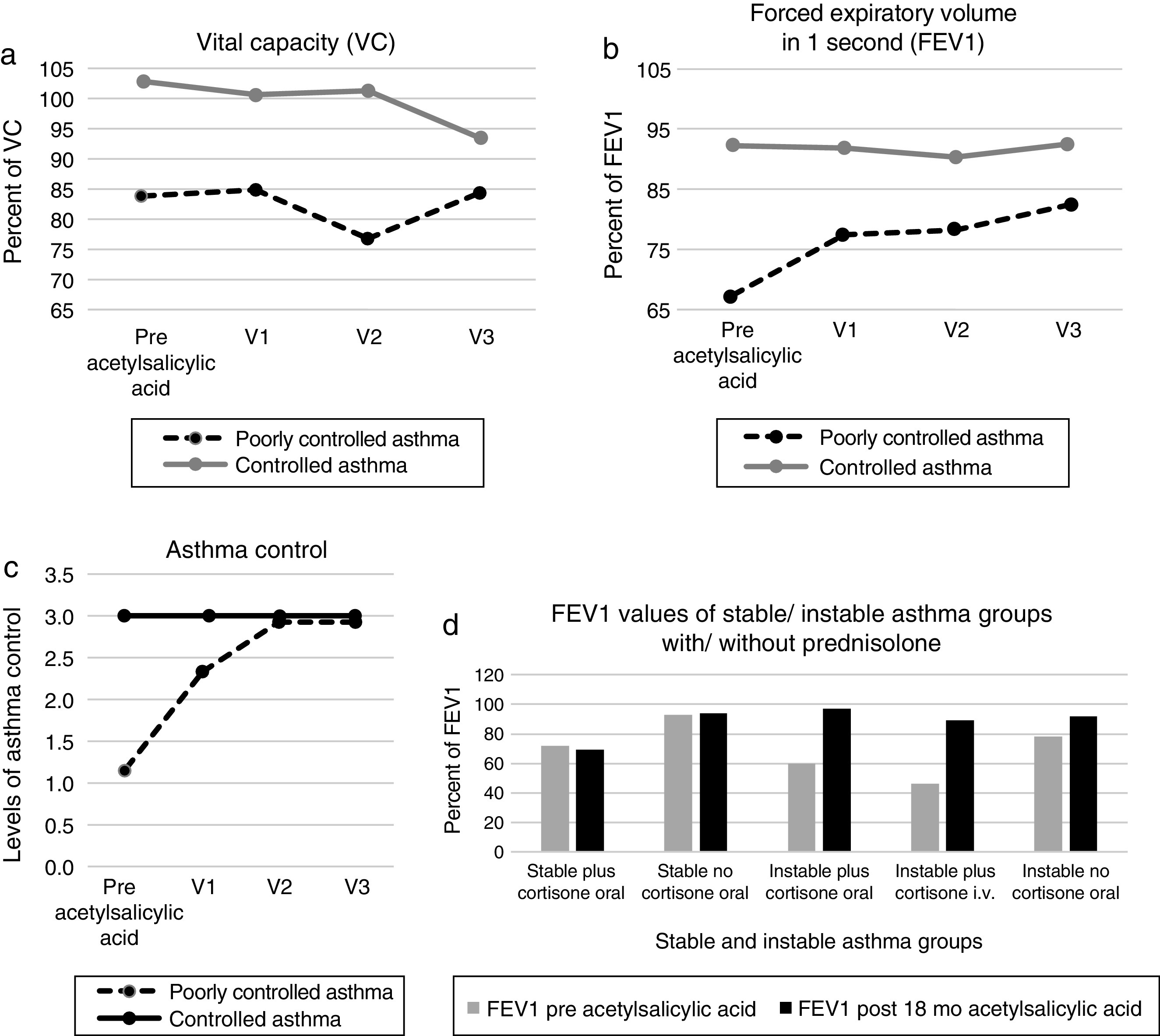

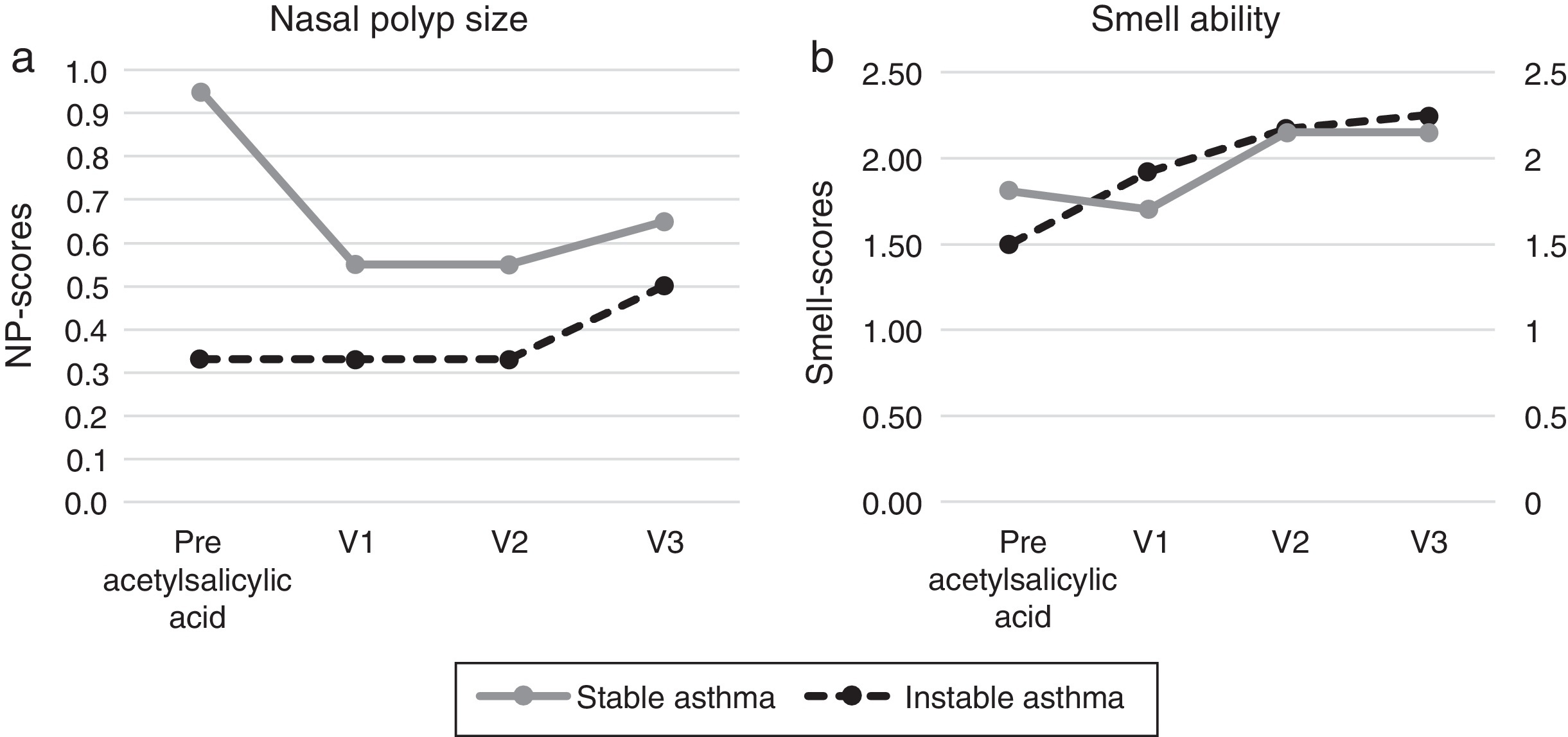

ResultsThirty-two patients were included in the study (uncontrolled/partially controlled asthma n = 12; controlled asthma n = 20). After 18 months of follow-up, the patients with poorly controlled asthma had significantly increased forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) values, as compared to the baseline (66–82%; p = 0.02), the levels of asthma control improved significantly (p < 0.01). The asthma medication was reduced. In the group of controlled asthma the FEV1 values did not increase significantly (91.9–92.4%; p > 0.05) and the asthma medication was constant. In relation to nasal parameters the sense of smell improved significantly in both groups, NP-scores did not differ significantly.

ConclusionsPatients with a poorly controlled asthma and NSAIDs hypersensitivity profit from an add-on aspirin therapy.

Asthma is a global respiratory health problem affecting 1-18% of the population in different countries.1 According to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), the levels of asthma symptom control can be divided into controlled, partially controlled and uncontrolled asthma forms.1 Intolerance to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be detected among 13–21% of the asthmatics.2, 3 For the asthmatics with nasal polyps (NP), the incidence of NSAIDs intolerance increases to 30%.4 This association has been termed as “aspirin triad”, “aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease” (AERD) or “NSAIDs hypersensitivity”.5, 6 The pathogenesis of the AERD is based on a shift from eicosanoids to leukotrienes.7 Depending in its severity, asthma can be treated with beta-2 mimetics, corticosteroids, leukotriene receptor antagonists, theophylline or anti-IgE antibodies.1 A further therapeutic option for asthmatics and NSAIDs hypersensitivity is the aspirin desensitization,8 where the patient is gradually introduced step by step to aspirin, and a daily maintenance dose is determined. The underlying mechanism of aspirin desensitization has until today not yet been completely clarified. Interestingly, following desensitization, there is an increase in the prostaglandin PGE2/leukotriene index in patients’ blood.9 To the best of our knowledge, clinical effects of aspirin desensitization in patients with a poorly controlled asthma and NSAIDs hypersensitivity have not yet been reported. For this reason, the aim of our study was to investigate the outcome of aspirin desensitization in patients with NSAIDs hypersensitivity and a poorly controlled asthma. We performed comparative analyses using the data obtained from the patients with controlled asthma and NSAIDs hypersensitivity who underwent aspirin therapy.

MethodsPatients routinely desensitized against at least 18 months in the Department of Pulmonology (Treuenbrietzen, Germany) or the ORL Department of the Charité University Hospital (Berlin) between 2009 and 2013 were included in this retrospective study. All patients enrolled in the study gave their informed consent. The inclusion criteria were NSAIDs sensitivity, nasal polyps, controlled or poorly controlled asthma.

Twelve patients (mean age 48 y, range from 32 y to 73 y, 4 men, 8 women) with poorly controlled asthma and 20 patients with controlled asthma (mean age 57.75 y, range from 44 y to 67 y, 8 men, 12 women) were included. The “poorly controlled asthma”-group consisted of ten patients with uncontrolled asthma and two patients with partially controlled asthma. Aspirin was recommended to be taken by both groups, in order to improve the nasal and asthma symptoms.

NSAIDs sensitivity was confirmed by oral aspirin provocation test; a positive reaction was a decline of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) ≥ 20% of baseline and profound rhinorrhea or nasal blockage.10 The patients were stepwise desensitized to oral aspirin in the hospital with a final daily aspirin maintenance dosage of 500 mg. The following desensitization protocol was used: day 1: placebo/placebo/placebo; day 2: 1/2/4/8; day 3: 10/20/40/80; day 4: 100/100/150; day 5: 200/200/500; from day 6: 500 mg orally administered aspirin.

Following parameters were evaluated:

Levels of asthma symptom control: Assessment of symptom control was done by strictly following the GINA criteria1 – see Table 1. Following groups of patients were identified:

1. Controlled or stable asthma group: well controlled asthma;

2. Poorly controlled or instable asthma group: partially controlled asthma/uncontrolled asthma.

Table 1. GINA assessment of asthma symptom control.

| Asthma symptom control | Levels of asthma symptom control | ||||

| In the past 4 weeks, has the patient had | Well controlled | Partially controlled | Uncontrolled | ||

| Day time asthma Symptoms more than twice/week | Yes□ | No□ | None of these | 1–2 of these | 3–4 of these |

| Any night waking due to asthma? | Yes□ | No□ | |||

| Reliever needed for symptoms more than twice/week | Yes□ | No□ | |||

| Any activity limitation due to asthma? | Yes□ | No□ | |||

Pulmonary function values: The peak expiratory flow (PEF) variability was measured before aspirin desensitization. The forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and vital capacity (VC) were measured by spirometry before and following aspirin treatment.

Use of asthma medication: The daily use and dosages of the asthma medication were documented. The daily dosages of inhaled corticoids (ICS low/medium/high dosage) and the asthma medication scores were obtained in accordance to GINA criteria.1 Prednisolone-dependent patients were separated from the dual GINA classification of severity. The medication was not changed 6 months prior to desensitization.

Nasal endoscopy: The Davos-staging of nasal polyps (NP) size was performed (0: no NP; 1: NP in middle meatus; 2: NP beyond middle meatus; 3: obstructing NP).11

Sense of smell: The subjective olfactory function was semi-quantitatively documented (0: no sense of smell; 1: mild sense of smell; 2: moderate sense of smell; 3: excellent sense of smell).

Follow-up: The patients were routinely examined before aspirin therapy, 6, 12 and 18 months (visit 1, 2 and 3) following aspirin therapy. Pulmonary and nasal parameters were documented.

Adverse events: Adverse events during aspirin induction and maintenance therapy were documented.

Statistics: A nonparametric test of independent samples (Mann–Whitney U test) was used to test the spirometric parameters FEV-1 and VC, asthma medication and the nasal polyps between patient groups. The levels of asthma control and smell were tested with the chi-squared test (p < 0.05).

ResultsPatients’ characterization prior to aspirin desensitization therapyThe mean FEV1-, VC values were significantly lower and PEF variability values higher in the poorly controlled asthma patients (p < 0.01). The nasal polyps size did not differ significantly (0.55/0.95; p = 0.21). The asthma medication score in poorly controlled asthma patients was significantly higher than in the controlled group (4.25/2.20, p < 0.01).

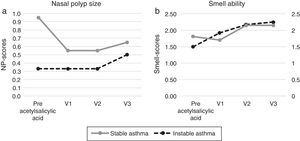

Patients with poorly controlled asthma following aspirin desensitization therapyIn relation to the symptoms of the asthma control levels four patients (33.3%) still had uncontrolled asthma and eight patients controlled asthma after 6 months (67%). After 12 months of aspirin therapy 11 patients had controlled asthma (91.7%) and one patient with uncontrolled asthma, which finally improved to partially controlled asthma after 18 months. The asthma control level of all visits following aspirin therapy improved significantly when compared to the baseline, p < 0.01. The mean FEV1 values increased from the initial 67.4% to 82.4% after 12 months (p 0.03). The VC values increased from the initial 83.9% to 87.8% (p 1.00), the size of nasal polyps from initial 0.33 to 0.50 (p 0.56). The sense of smell improved significantly after 18 months from 1.85 to 2.25 (p 0.02) (Figure 1, Figure 2). The asthma medication score declined from 4.2 to 3.9 (p < 0.18).

Figure 1. Pulmonary function values before and after acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) desensitization therapy ((a) Vital capacity (VC) values; (b) forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) values; (c) asthma control levels (1: uncontrolled; 2: partial controlled; 3: controlled) and (d) FEV1 values of prednisolone dependent patients).

Figure 2. Nasal parameters before and after acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) desensitization therapy ((a) Nasal polyps and (b) smell ability).

Patients with controlled asthma following aspirin desensitization therapyNo patient developed uncontrolled asthma during the follow-up examination. The mean FEV values were 92% before and 92.4% following therapy, the VC values 101.6% before and 96.3% following aspirin desensitization (p ≥ 0.50). The nasal polyps scores decreased (0.95/0.65; p 1.00). The sense of smell improved from 1.50 to 2.15 (p 0.16), the sense of smell scores improved significantly after 12 months (p = 0.03) (Figure 1, Figure 2). The asthma medication level in this group was constant 2.2 (p = 1.00).

Comparison of the poorly controlled and the controlled asthma patients following 18 months of aspirin therapyAfter 18 months, the FEV1 values and the size of nasal polyps did not differ significantly between the patient groups, the VC values from the poorly controlled asthma group were significantly lower (84.4%/93.5%; p 0.03). In addition, the medication score was still significantly elevated in the poorly controlled asthma group (p < 0.01).

Examination of corticosteroid-dependent patientsPatient group with controlled asthma and oral prednisoloneOne patient was on permanent oral 10 mg prednisolone. The mean FEV1 value decreased from initial 72% to 69%, the nasal polyp size increased from 0 to 2 after 18 months aspirin therapy.

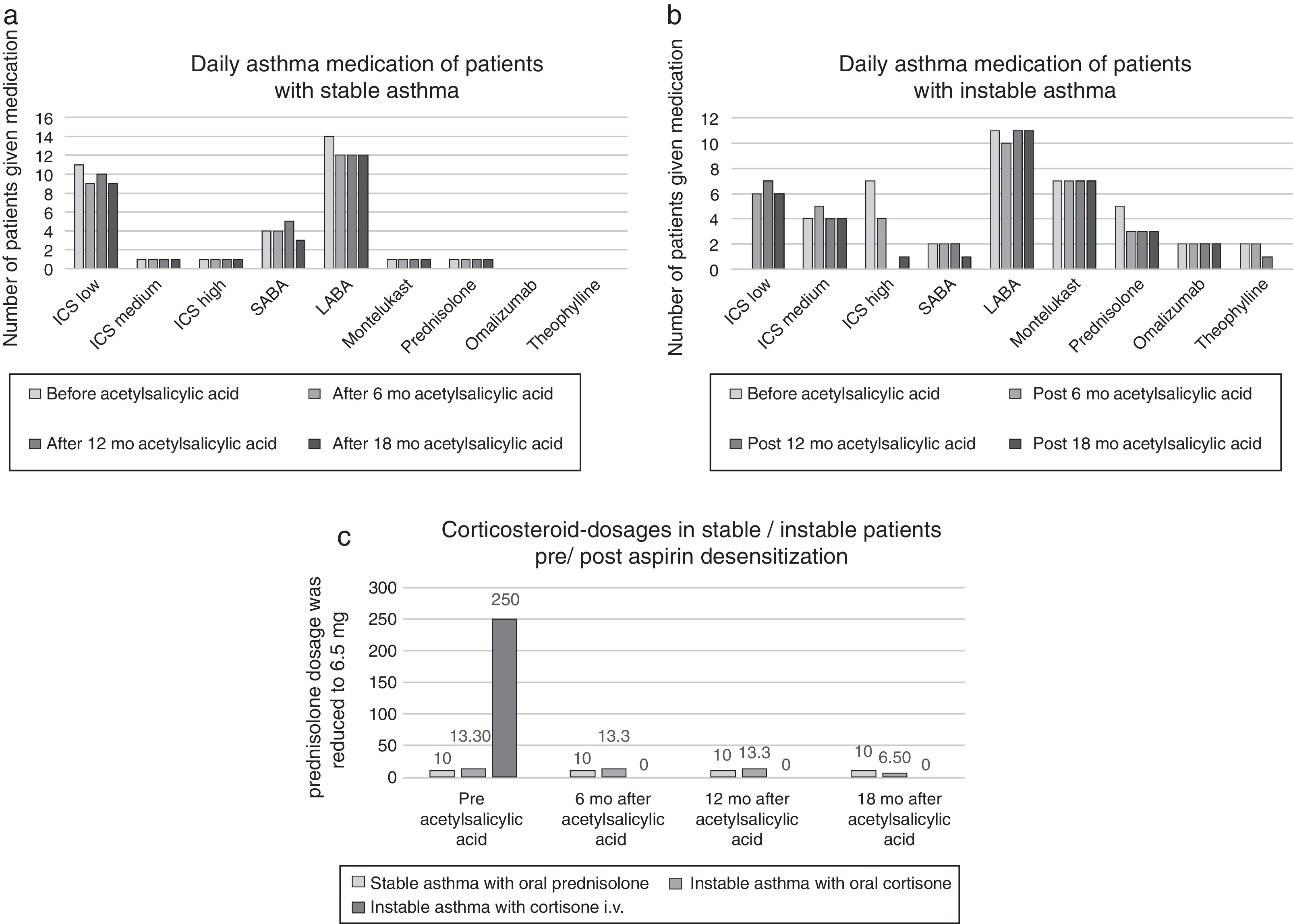

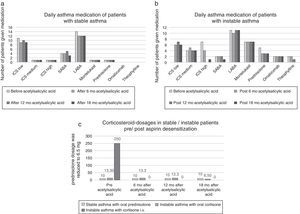

Patient group with uncontrolled asthma and oral prednisolonePrior to desensitization, four patients were on permanent oral prednisolone (mean dosage 13.3 mg). After 18 months therapy one patient had partial controlled asthma and the other patients had controlled asthma. The mean prednisolone dosage was reduced to 6.5 mg (Figure 3). The mean FEV1 value increased from 60% to 97% and the nasal polyp size from 0 to 0.67.

Figure 3. Asthma medication parameters before and after acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) desensitization therapy ((a) asthma medication of stable asthma patients; (b) asthma medication of instable asthma patients and (c) corticoiddosages of asthma patients).

Patient group with uncontrolled asthma and intravenous prednisoloneOne patient had an asthma exacerbation before aspirin therapy and was treated with an intravenous prednisolone pulse therapy (initial dosage 250 mg). The FEV1 was 46% and the nasal polyp size 0. After 18 months of aspirin desensitization, the asthma was controlled, FEV1 was 89% and the nasal polyp size 0. Parenteral prednisolone therapies were not repeated.

Adverse eventsIn three patients with poorly controlled asthma, administration of aspirin induced recurrent asthma attacks. These patients were initially administered 150 mg or 300 mg aspirin. During the second desensitization appointment, the dosage of aspirin has been increased to 500 mg, which induced no complications. During the maintenance therapy, no adverse events were observed.

DiscussionThis retrospective study demonstrates for the first time that the patients with a NSAIDs-hypersensitivity and poorly controlled asthma can benefit from aspirin desensitization. Following 6 months desensitization, the asthma control levels significant improved. In epidemiological studies, the asthma severity in NDAIDs hypersensitive patients was higher and FEV1 values lower, as compared to NSAIDs tolerant asthma patients.12, 13 In both studies, aspirin therapy was not performed. The pathomechanism of the NSAIDs hypersensitivity is based on an altered cyclooxygenase metabolism.14 The effect of aspirin desensitization is not yet really clear. Under the daily aspirin administration, a significant increase of the prostaglandin E2/leukotriene index9 appears to take place.

According to GINA criteria, the main goal of asthma management is to gain optimal asthma control.1 Depending on the severity of the disease, a multimodal therapy involving beta-2-mimetics, corticosteroids, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and theophylline or anti-IgE antibodies is necessary. Dahlén et al. examined the effects of leukotriene receptor antagonist montelukast in NSAIDs-hypersensitive patients and found significantly improved FEV1 values.15 Some patients in our study were treated with montelukast (see Figure 3). Since no changes in medication were made, our results appear to be aspirin-dependent.

Berges Gimeno examined 126 patients (daily 1300 mg aspirin) and registered over one year a significant reduction of nasal symptoms and a significant reduction in the number of short-term prednisolone treatments due to asthma.8 In our study the oral prednisolone dosage was reduced from the original mean 13.3 mg to mean 6.5 mg in instable asthma patients. One instable asthma patient who received intravenous prednisolone during asthma exacerbation prior to aspirin desensitization, no longer needed corticosteroids after desensitization. In the work of Stevenson, inclusion criteria for the aspirin desensitization required a FEV1 variability of <10% and FEV1 values of >60%.16 In our study, we included patients with PEF variability greater than 10% (instable asthma 45%; stable asthma 14%). The mean FEV1 values in our sample were better than Stevensons’ inclusion criteria (instable asthma 67%; stable asthma 92%). We demonstrated that the FEV1 values significantly improved in the poorly controlled asthma patients following 12 months of aspirin therapy (p 0.03). Also, the FEV1 values of corticosteroid-dependent patients increased following aspirin therapy in our study (Figure 3).

Havel et al. found that 56 patients with NSAIDs hypersensitivity receiving aspirin for more than 18 months (daily 500 mg aspirin) following nasal sinus surgery have improved in relation to asthma and nasal complaints.17 The spirometric examinations were not done in follow-up. A significantly lower nasal polyp size in patients receiving aspirin was observed, as compared to the patients not receiving aspirin. In our study, the difference in nasal polyp size before and after aspirin therapy was not significant, which may depend on our inclusion criteria, where we did not compare nasal polyp groups with and without aspirin desensitization therapy and our patients were not all included immediately after surgery.

Therapy of patients with therapy-resistant asthma and NSAIDs hypersensitivity requires a multimodal therapeutic concept according to pulmonary guidelines. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first retrospective examination of patients with NSAIDs hypersensitivity and poorly controlled asthma receiving aspirin therapy. Concerning the asthma symptom control levels, a significant improvement was observed (p < 0.01). Although the patients certainly profit from the asthma medication administered according to GINA guidelines, they can also profit from an add-on aspirin therapy. Further studies with larger samples are necessary to further validate this therapy. This exploratory retrospective analysis will be continued in order to compare NSAIDs sensitive asthmatic patients subjected to NSAIDs desensitization with the patients receiving standard therapy.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Author contributionUFR: conceived the study, performed patients examinations, collected and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

SM.Z: performed patients examinations and collected the data.

AJ.S: interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

HO: supervised the project, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

UR: conceived the study, performed patients examinations, supervised the project and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Received 24 September 2014

Accepted 5 June 2015

Corresponding author. ulrike.foerster@charite.de