Prolonged stay in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) can cause muscle weakness, physical deconditioning, recurrent symptoms, mood alterations and poor quality of life.

Physiotherapy is probably the only treatment likely to increase in the short- and long-term care of the patients admitted to these units. Recovery of physical and respiratory functions, coming off mechanical ventilation, prevention of the effects of bed-rest and improvement in the health status are the clinical objectives of a physiotherapy program in medical and surgical areas. To manage these patients, integrated programs dealing with both whole-body physical therapy and pulmonary care are needed.

There is still limited scientific evidence to support such a comprehensive approach to all critically ill patients; therefore we need randomised studies with solid clinical short- and long-term outcome measures.

Uma estadia prolongada na Unidade de Cuidados Intensivos (UCI) pode causar fraqueza muscular, descondicionamento físico, sintomas recorrentes, alterações de humor e má qualidade de vida.

A fisioterapia é, provavelmente, o único tratamento com potencial para aumentar nos cuidados a curto e longo prazo aos pacientes internados nestas unidades. A recuperação das funções físicas e respiratórias, retirar a ventilação mecânica, prevenção de efeitos do repouso na cama e melhoria do estado de saúde são objectivos clínicos de um programa de fisioterapia nas áreas médicas e cirúrgicas. Para tratar estes pacientes, são necessários programas integrados que englobem tanto a fisioterapia global como os cuidados respiratórios necessários.

A evidência científica para apoiar esta abordagem abrangente para todos os doentes críticos é ainda limitada; portanto, são necessários estudos aleatorizados com medidas de resultados a curto e longo prazo.

Advances in the management of critically ill patients admitted to intensive (ICU) or respiratory intermediate intensive care units (RIICU) have improved hospital mortality and morbidity, leading to a growing population of patients with partial or complete dependence on mechanical ventilation and other ICU therapies.1–3

Clinical consequences of prolonged mechanical ventilationProlonged Hospital stay and difficulty with or lack of response to therapies can often cause severe complications such as muscle weakness, physical deconditioning, recurrent symptoms, mood alterations and poor quality of life.4,5 Patients needing prolonged mechanical ventilation, may suffer from “chronic critical illness” involving myopathy related weakness, neuropathy, loss of lean body mass, increased adiposity, and anasarca.4–6 This syndrome may contribute to low target organ hormone levels and impaired anabolism,5,7 increased prevalence of difficult-to-eradicate infections,8 coma or protracted or permanent delirium,9 skin wounds, edema, incontinence, and prolonged immobility.10,11The role and workload of physical therapists in an ICU is different in different European countries,12 but common to all is a growing need for physiotherapy programs in the short- and long-term care of patients admitted to ICUs or RIICU.13–16 The recovery of physical and respiratory functions, discontinuation of mechanical ventilation, prevention of the effects of bed-rest and improvement in health status are proven clinical results of a physiotherapy program in these medical and surgical areas.17–20

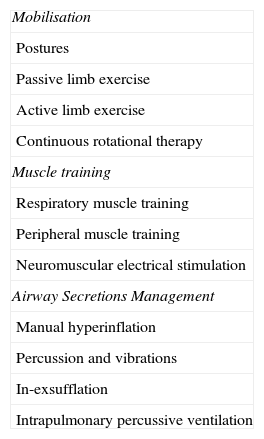

The aims of any physical therapy program in critically ill patients is to apply advanced cost-effective therapeutic tools to decrease complications and the patient's ventilator-dependency and in this way decrease risks of complications associated with bed-rest, to improve residual function, to prevent the need for new hospitalisations and to improve the health status and quality of life. Physical therapy as a part of the overall care of patients undergoing cardiac, upper abdominal, and thoracic surgery, may prevent and treat respiratory complications such as secretion retention, atelectasis, and pneumonia by means of different techniques. Early physical therapy may prevent difficult weaning, limited mobility and ventilator dependency21,22 (Table 1).

Physiotherapy techniques in the ICU.

| Mobilisation |

| Postures |

| Passive limb exercise |

| Active limb exercise |

| Continuous rotational therapy |

| Muscle training |

| Respiratory muscle training |

| Peripheral muscle training |

| Neuromuscular electrical stimulation |

| Airway Secretions Management |

| Manual hyperinflation |

| Percussion and vibrations |

| In-exsufflation |

| Intrapulmonary percussive ventilation |

Prolonged immobility is a main cause of muscle weakness in patients admitted to ICU, conversely early physiotherapy has an important role in the recovery of these patients. Early physical activity is feasible and is a safe intervention following the initial cardio-respiratory and neurological stabilisation.23,24 Early mobilisation and muscle training can improve functional outcomes, cognitive and respiratory conditions in these critically ill patients,24 reducing the risks of venous stasis and deep vein thrombosis.25 Postures, passive or active limb movements and Continuous Rotational Therapy (CRT) are considered the principal strategies to mobilise patients.

PosturesProne position has been shown to result in short-term gain in oxygenation, in improvement of ventilation and perfusion mismatch and of the residual lung capacity.26–29 Improvements in lung function and atelectasis have been also shown in patients with unilateral disease when positioned on their side, lying with the affected lung uppermost.30,31 Despite their physiological rationale,17 these easy techniques are still not widely used and it is still unclear whether the reported physiological improvements can be associated with improvements of stronger clinical outcomes like mortality.

Passive and active limb exercisePassive, active assisted, or active resisted limb movements are aimed at maintaining the range of motion of the joints, at improving soft-tissue length and muscle strength, and decreasing the risk of thromboembolism.32

Quadriceps force and functional status was the same in patients undergoing the addition of early mobilisation to standard physiotherapy compared to standard physiotherapy alone. However, the total distance they walked, the isometric quadriceps force and the perceived functional well-being were significantly better with early mobilisation.33 A gradual mobility protocol for both upper and lower limbs resulted in feasibility, safety and decreased hospital length of stay in acute patients requiring mechanical ventilation.34 Supported arm training in addition to normal physiotherapy35 gave similar positive results in patients recently weaned from mechanical ventilation in a RIICU (Fig. 1).

Continuous rotational therapyThis refers to specialised beds used to turn patients continuously along the longitudinal axis up to an angle of 60° onto each side, with preset degree and speed of rotation. This treatment can prevent sequential airways closure, and pulmonary atelectasis, reduce the incidence rate of lower respiratory tract infection and pneumonia, the duration of endotracheal intubation and the length of hospital stay.36–40

Muscle trainingIt is well known that muscle mass and its ability to perform aerobic exercise invariably declines with inactivity.41 In critically complex patients, skeletal muscle training aims to strengthen, thus potentially increasing the patient's ability to perform Activities of Daily Life (ADL). In these patients, a tailored training program seems to be very effective in speeding weaning, in improving hospital survival, and in reducing risks associated to hospital-stay.42

Respiratory muscle trainingRespiratory muscle weakness, imbalance between muscle strength and the load of the respiratory system and cardiovascular impairment are major determinants of weaning failure in ventilated patients. In ICU patients these factors and the excessive use of controlled mechanical ventilation, may lead to rapid diaphragmatic atrophy and dysfunction.43 Nevertheless, the rationale for respiratory muscle training in ICU is still controversial. Indeed, the diaphragm of COPD patients is as valid as that of a healthy person in generating pressure at comparable lung volumes,44 showing an adaptive change toward the slow-to-fast characteristics (resistance to fatigue) of the muscle fibres due to increased operational lung volume.45

There has been a debate in recent literature about the potential role of Inspiratory Muscle Training as a component of pulmonary rehabilitation in severely disabled COPD and in neuromuscular patients,46,47 which is aimed at improving their strength and reducing the load perception of the respiratory system. Studies on ICU ventilatory-dependent COPD patients have also shown that respiratory muscles training may be associated with a favourable weaning outcome.48,49

Peripheral muscle trainingProlonged inactivity is more likely to cause skeletal muscle dysfunction and atrophy in antigravity muscles, with reduced capacity to perform aerobic exercise.41,50 In severely disabled patients peripheral muscle training (both passive and active training lifting weights or pushing against a resistance with the limbs), produces specific gain of strength and recovery of ADL, although the evidence of effects after an episode of acute respiratory failure is not specified.51 We have found that selective arm training added to the benefits (exercise tolerance and perception of dyspnoea) of standard physiotherapy.35

Neuromuscular electrical stimulationNeuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) can induce changes in muscle function without any form of ventilatory stress in severely ill patients who are unable to perform any activity.52 However, no clinical studies have yet clearly demonstrated the additional effect of NMES on exercise tolerance when compared with conventional training. NMES can be easily used in the ICU, applied to lower limb muscles of patients lying in bed. Patients with COPD53,54 or with congestive heart failure55 are more likely to benefit. NMES has been also considered as a means of preventing ICU polyneuromyopathy, a frequent complication in the critically ill patients.56

Airway secretionsIncrease of bronchial secretions (either due to muco-ciliary dysfunction or to muscular weakness) may affect respiratory flow and increase the risk of nosocomial pneumonia.8 Chest physiotherapy should prevent such complications by improving ventilation and gas exchange, and by reducing airway resistance and the work of breathing.15 Several manually assisted techniques (manual hyperinflation, percussions/vibrations) and mechanical devices (in-exsufflator) are often applied to facilitate removal of excess of mucus (Table 1).

Manual hyperinflationThis respiratory technique is aimed at preventing pulmonary collapse (or re-expanding collapsed alveoli), improving oxygenation and lung compliance, and facilitating the movement of secretions toward the central airways.57 Manual hyperinflation does not have a standard practice; the possible physiological side effects of delivered air volume, flow rates and airway pressure must be carefully considered, especially in patients under mechanical ventilation.58–60 Increase in air volume with this technique can be obtained both manually or with assisted mechanical ventilation, each producing similar benefits in clearing excessive mucus.61,62

Percussion and vibrationsManual percussion and vibrations (clapping a selected area and then compressing the chest during the expiratory phase) are commonly used to increase airway clearance and are often associated with postural drainage. Currently, in critical ventilated patients with a normal cough competence, increase of mucus clearance is achieved without a significant change of blood gases and lung compliance.15,63,64

In-exsufflationThe mechanical in-exsufflator promotes removal of excessive mucus by inflating the airways with a large air volume that rapidly is exsufflated by a negative pressure, thus simulating the physiological mechanism of cough.65–67 The safety and the clinical advantage (avoidance of tracheostomy and/or endotracheal intubation) of this device when compared with conventional chest physiotherapy in hospitalised neuromuscular patients with recent upper respiratory tract infection has been shown.68,69 The usefulness of these techniques in allowing for extubation in patients judged as needing tracheostomy has been recently outlined.70

Intrapulmonary percussive ventilationIntrapulmonary Percussive Ventilation creates a percussive effect in the airways thus facilitating mucus clearance through direct high-frequency oscillatory ventilation which is able to help the alveolar recruitment.71 This effect has been successfully shown during both acute and chronic phases in patients with respiratory distress,72 neuromuscular disease,73 and pulmonary atelectasis with or without consolidation.74 In hospitalised COPD patients with respiratory acidosis, this technique has been shown to prevent the deterioration of the acute episode, thus avoiding endo-tracheal intubation.75 In tracheostomised patients recently weaned from mechanical ventilation the addition of Intrapulmonary Percussive Ventilation to standard chest physiotherapy was associated with an improvement of oxygenation and expiratory muscle performance thus leading to a substantial reduction in the risk of pneumonia.76

ConclusionDue to the increasing number of ICU admissions and the global risk of complications and mortality over the following years,3,77 comprehensive programs including physiotherapy should be implemented to speed-up the patients’ functional recovery and to prevent the complications of prolonged immobilisation especially in ventilator-dependent or difficult- to wean patients.18,78 To manage the multiple and complex problems of these patients, integrated programs dealing with both whole-body physical therapy and pulmonary care are needed.13,14

There is still limited scientific evidence to support such a comprehensive approach to all critically ill patients; therefore we need randomised studies with solid clinical short- and long-term outcome measures.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.