Dear Editor,

We would like to present the first case of a patient coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), diagnosed with pulmonary sarcoidosis in the context of a triple therapy with pegylated-interferon, ribavirin and telaprevir.

A 50-year-old man, diagnosed with HIV in 1993, stage A2, treated with antiretroviral therapy: tenofovir, emtricitabine and raltegravir. In 2004 was diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C, genotype 1a with F2 degree of liver fibrosis, and treated during 24 weeks with pegylated-interferon and ribavirin, presenting partial response.

In 2013, the patient was treated with telaprevir-based triple therapy according to the regimen: telaprevir 2250 mg/day for the first 12 weeks; pegylated-interferon 2a 180 mcg/week and ribavarin 1200/day for a total of 48-weeks. At the time of starting treatment, the patient had a F3 degree of fibrosis determined by Fibroscan® (9.9 kPa), a HCV VL of 5,810,000 IU/ml, CT IL28B polymorphism, a CD4 count of 544 cells/mm3 (32%), HIV VL <20 copies/ml, ALT of 75 IU/L and AST of 62 IU/L, the rest of the analytical was normal. During the following weeks, he did not show relevant adverse events.

At week 43, the patient started having dyspnea and chest pain without fever, symptoms that worsened in the following weeks. The chest radiography showed bilateral diffuse interstitial lung disease, ground-glass opacities and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Also, a lung scan was performed and no findings of acute pulmonary embolism were observed. The gas analysis showed: pCO2: 31.2 mmHg, pO2: 68.2 mmHg, O2 saturation: 95.9% and pH: 7.47, and the biochemistry showed an angiotensin-converting enzyme value greater than 100.

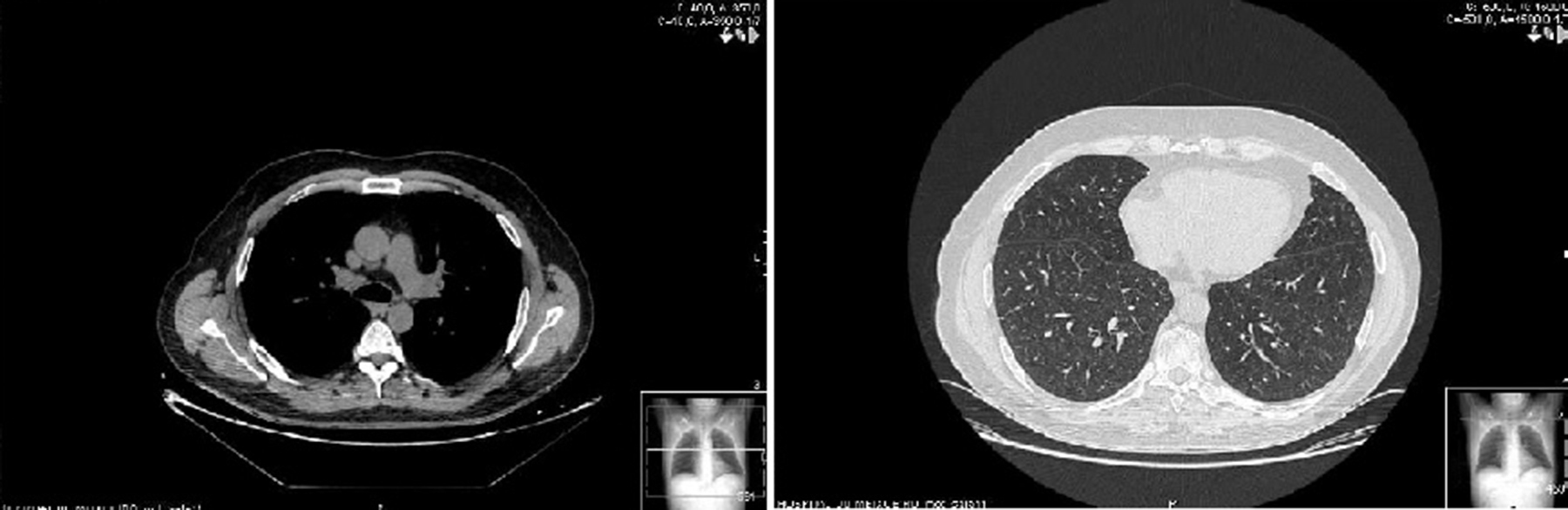

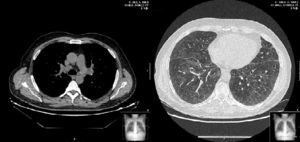

Two weeks later, the patient presented clinical improvement (after drug treatment with antibiotics and bronchodilators) but with persistent injury in chest radiography, so a thoracic CT was performed, showing bilateral and diffuse ground-glass opacities, multiple centrilobular micronodules (Figure 1) and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Bronchoscopy was normal, and transbronchial biopsy showed the presence of non-necrotizing granulomas. Ziehl Neelsen, and Groccott staining were negative, as PCR and mycobacteria culture. After completing HCV treatment, the clinical course of the patient was favorable, showing the following thoracic CT gradual improvement in lung and lymph node involvement, and finally, a year later, the resolution of the disease (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Sarcoidosis in 50 years-old man, coinfected with HIV and HCV, and treated with telaprevir-based triple therapy. Thin-section of thoracic CT shows bilateral and diffuse ground-glass opacities, and multiple centrilobular micronodules.

Figure 2. Sarcoidosis in 50 years-old man, coinfected with HIV and HCV, and treated with telaprevir-based triple therapy. Thin-section of thoracic CT shows sarcoidosis resolved a year after stopping HCV treatment. Small calcified micronodules are observed.

HCV VL values became undetectable at week 8 and remained undetectable 24 weeks after completion of HCV therapy, reaching sustained viral response (SVR). In addition, the liver function values normalized after 28 weeks of treatment (ALT 31 IU/L, AST: 35 IU/L), and remained within the normal range 24 weeks after completion of antiviral therapy.

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous disease of unknown origin and multisystemic character, in which lung, liver, lymphoid system and skin are the most affected organs.1 Although its etiology is unknown, probably an exaggerated response to various antigens as mycobacterias, environmental agents or autoantigens, produces an abnormal activation of CD4+ T cells, activating peripheral blood monocytes, and causing the formation of granulomas.2

Diagnosis of sarcoidosis is often a matter of exclusion, as in our case; there is no specific test for the condition. All the findings of our case raised the possibility of a differential diagnosis of granulomatous inflammation caused by infection or sarcoidosis. Findings on cultures for viral, fungal and mycobacterial organisms were negative. Radiological findings and clinical manifestations were consistent with an atypical pulmonary sarcoidosis. Similar clinical findings were reported in other cases of sarcoidosis associated with interferon.1, 3, 4

Interferon is a cytokine with immunomodulatory activity on T lymphocytes, which is successfully used in the treatment of hepatitis C. Several adverse effects have been described for interferon therapies, like hematologic symptoms, flu-like symptoms, and cutaneous events,5 and although the exact mechanism of action is unknown, interferon is also associated with the occurrence of certain immunological diseases like hemolytic anemia, hypothyroidism, and sarcoidosis.3, 5 The majority of patients achieved spontaneous resolution of sarcoidosis after stopping treatment with interferon, and there is also evidence of remission in spite of continuing treatment, demonstrating that interferon may play a role in its appearance, but not in the maintenance, so the decision to continue treatment should be assessed depending on the risk-benefit balance. In our case, the patient continued the treatment until completion, reaching SVR, and showing clinical and radiological improvement since the end of treatment.

The systemic manifestations of sarcoidosis are usually treated with oral steroids, but it often increases the hepatitis C viral load. In this case, it was not necessary to use corticosteroid treatment, and sarcoidosis was resolved after stopping HCV treatment, which may indicate the role of HCV treatment in his appearance.

Although there are several articles about the relationship between sarcoidosis and interferon, their relationship with ribavirin cannot be ruled, because it can activate the Th1 helper lymphocytes, or even with telaprevir, this occurred in another case of sarcoidosis in a patient treated with telaprevir, ribavirin and standard interferon 3 times per week.4

This case draws attention to this serious side effect that some patients may experience during the antiviral treatment, and it is essential that the diagnosis of sarcoidosis is considered in patients with compatible clinical findings.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Corresponding author. di_parente@hotmail.com