To evaluate the degree to which evidence from large clinical trials can be applied to patients treated in a local hospital cohort of COPD outpatients.

MethodsThe authors selected seventeen RCTs identified in a systematic way from GOLD 2019 consensus document, and applied their inclusion and exclusion criteria to a real-world cohort of a previous cross-sectional study of 303 COPD outpatients included consecutively.

ResultsWhen the inclusion criteria of the 17 RCTs were applied to a real-world cohort of COPD outpatients, only a small portion of them were eligible to participate in the referred trials, from 4.29% to 60.07%. However, when both the inclusion and the exclusion criteria were applied, only as little as 3.63% to as much as 40.59% of patients were eligible to participate. Hence, only a small fraction of patients from this cohort could benefit from the findings of these RCTs.

ConclusionsThere is a need to complement the efficacy evidence provided by large RCTs according to the extent to which their results, designed to target significant patient populations, can be applied to typical patients treated in routine clinical practice.

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) has significantly changed the practice of medicine since the early 1990s. Well-designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs), together with systematic reviews and meta-analysis, remain the cornerstone of clinical research, and provide the basis for guideline recommendations.1 Guidelines reduce uncertainty and promote the standardisation of clinical practice.2 A number of significant RCTs, published in the current decade, have contributed extensively to the scientific evidence related to the treatment of COPD patients. RCTs are the gold-standard for safety and efficacy evaluations of new drugs. They present strong internal validity, with narrow inclusion criteria and demanding exclusion criteria, to reduce bias. Their homogeneous highly-selected populations ensure that only exposure to treatment differs between the arms of the study.3 Therefore, patients enrolled in RCTs significantly differ from those treated in everyday clinical practice, reducing the possibility of extrapolation of their findings to unselected patient populations.4 Pragmatic trials and other real-world studies can be performed to complement RCTs, providing evidence of drug effectiveness in the heterogeneous populations of clinical practice.5 There is no robust knowledge of how representative patients enrolled in large RCTs are of a typical patient population for whom they intend to develop their findings and conclusions.6 Furthermore, it was not known how representative these patients are of a Portuguese population of patients with COPD. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the degree to which evidence from RCTs can be applied to a cohort of patients treated in the out-patient clinic of Hospital de Guimar.·es.

MethodsStudy designThis is a retrospective analysis, using a pre-existing cohort of COPD out-patients. We applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the selected RCTs to COPD patients observed in our routine clinical practice, and diagnosed according to GOLD criteria.7 From March 2016 to May 2017, participants were recruited consecutively in the outpatient pulmonary clinic of Guimar.·es Hospital, a middle-sized public hospital, treating patients from an urban and rural background.8 The only exclusion criteria were refusal to participate and inability to understand simple questionnaires.

Selection of RCTsThe GOLD strategy has a worldwide influence in the management of COPD patients, and we searched for RCTs with a significant impact on the pharmacologic management of COPD. They had to fulfil the following conditions:

- -

Cited in the GOLD 2019 consensus document,9 in chapter 3, ..úEvidence supporting prevention and maintenance therapy..Ñ, section on ..úPharmacological therapy for stable COPD..Ñ, and chapter 4 ..úManagement of stable COPD..Ñ, section on ..úTreatment of stable COPD: pharmacological treatment..Ñ.

- -

Related to inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting ..2-agonists or long-acting anticholinergic therapy.

- -

Related to single or combination inhaled therapy.

- -

RCTs published in the present decade (from 2010 to 2019).

- -

RCTs with at least 400 COPD patients at randomisation, and lasting 52 weeks or more.

- -

RCTs studying only COPD patients diagnosed according to GOLD criteria, or having a history of COPD as defined by the American Thoracic Society or the European Respiratory Society.

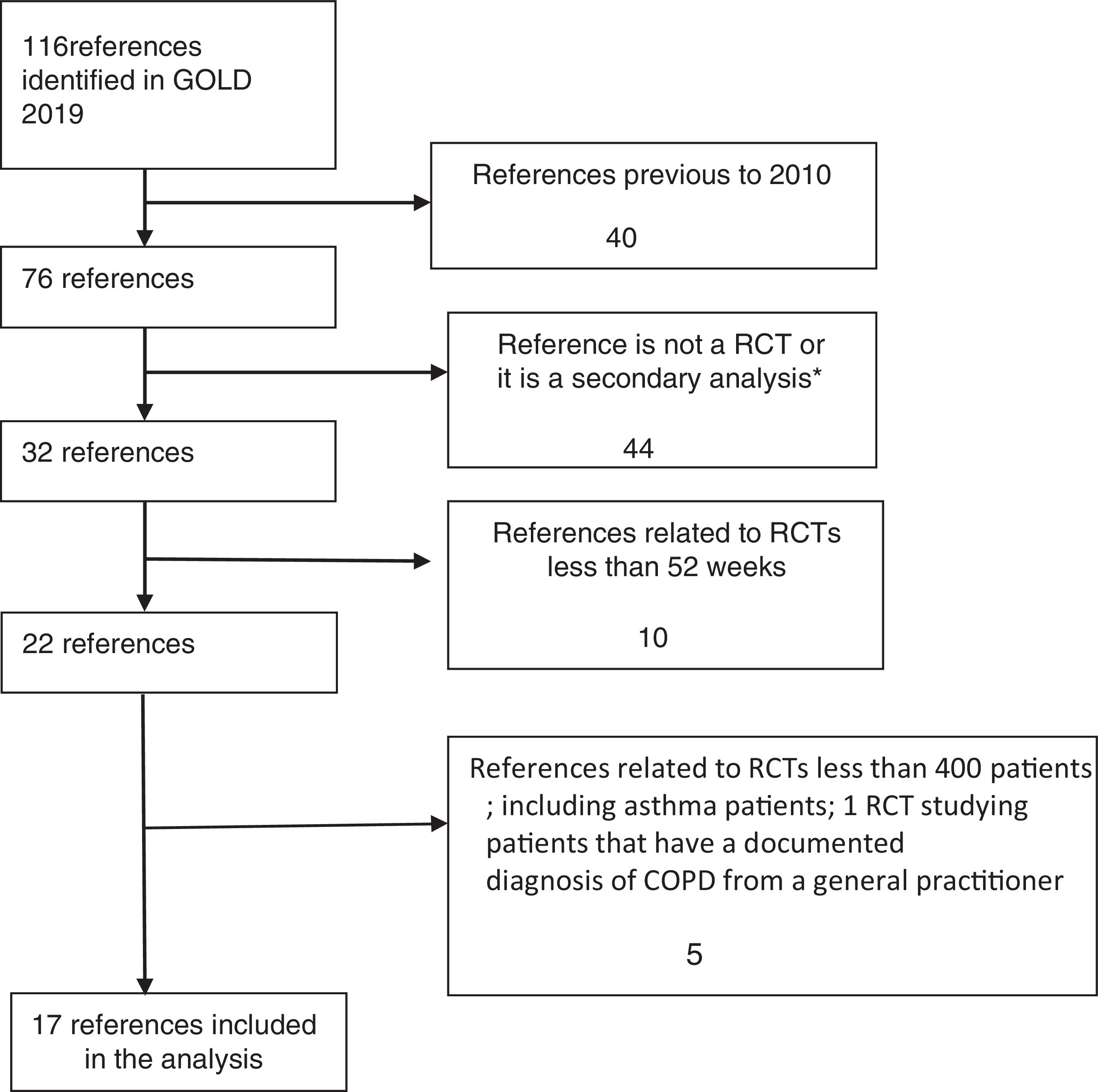

RCTs were identified in a systematic way, and the flow diagram related to the extraction of RCTs from GOLD 2019 strategy is described in Fig. 1.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were obtained from published papers and/or described in the on-line supplementary appendixes.10...26 Secondary analysis, as systematic reviews, with or without meta-analysis, post hoc analysis and pooled analysis were excluded, because they shared the same populations studied.

Data sourceThe main demographic, clinical and functional characteristics of 303 COPD patients are described in Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and functional characteristics of COPD patients.

| Characteristics | n=303 |

|---|---|

| Male gender | 241 (79.5) |

| Mean age (years) | 67.5..10.2 |

| Age ... 65 Years | 186 (61.4) |

| Education level ..± 3 school years | 89 (29.4) |

| Very low monthly income (< 530 Euros) | 197 (65.7) |

| Mean smoking amount (pack/years) | 49.3..32.4 |

| Current smokers / ex-smokers | 224 (73.9) |

| Never smokers or < 10 pack/year | 90 (29.7) |

| Occupational exposure | 164/295 (55.5) |

| Indoor exposure in women | 37/58 (63.8) |

| Alfa-1-AT deficiency / ZZ genotype | 12 (3.9) / 7 (2.3) |

| Previous history of asthma | 82/299 (27.4%) |

| mMRC grade ... 2 | 185 (61.1) |

| CAT score ... 10 | 152 (72.4) |

| Frequent ECOPD (... 2 / previous year) | 115 (38.0) |

| GOLD stage: | |

| I | 30 (9.9) |

| II | 127 (41.9) |

| III | 106 (35.0) |

| IV | 40 (13.2) |

| Gold 2017 classification: | |

| A | 70 (23.1) |

| B | 120 (39.6) |

| C | 7 (2.3) |

| D | 106 (35.0) |

Data shown as n (%); many different exposures relevant for COPD overlapped in the same patients.

Abbreviations: Occupational exposure, self-reported occupational exposure to gas, fumes and dust relevant to COPD; Indoor exposure, sustained indoor-exposure to household air pollution from coal and biomass fuel combustion in women; Alfa-1-AT, alfa-1-antitrypsin; mMRC, Medical Research Council Dyspnea Questionnaire; CAT, COPD Assessment Test; ECOPD, COPD exacerbations; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

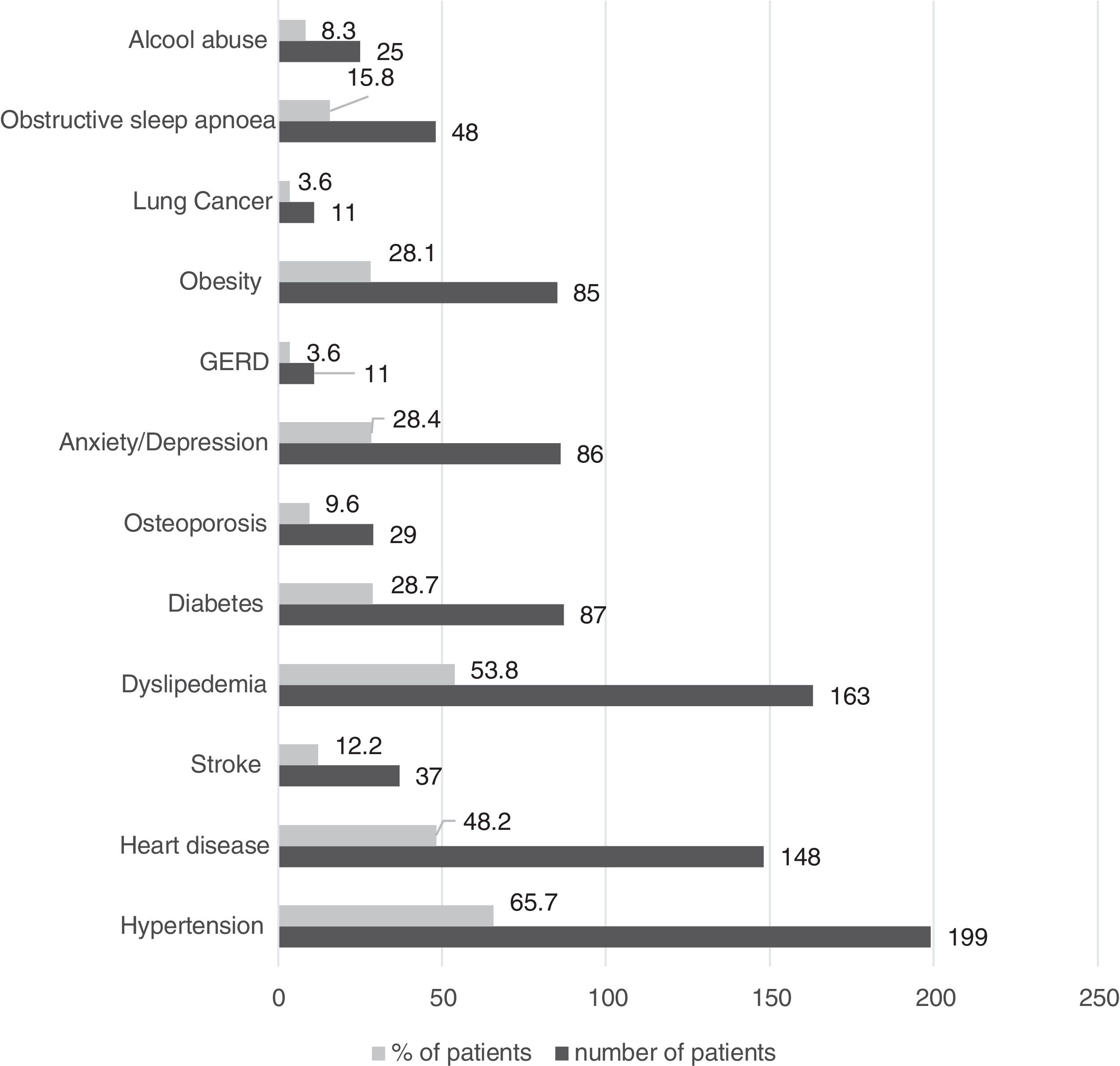

Only 9.5% of patients reported no comorbid conditions, and the most prevalent are presented in Fig. 2.

The mean post-bronchodilator FEV1% was 53.2..19.7, referenced according to the Global Lung Function Initiative predict equations (GLI 2012).27 A comprehensive report of patients... characteristics is described and published elsewhere.8 The statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

ResultsTable 2 describes the largest possible number and percent of the 303 patients from the Guimar.·es Hospital Cohort (HGC) who met the 17 RCTs inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Patients from the HGC who could participate in the referred RCTs.

| RCTsREF(2010 / 2018) | Patients from HGC meeting the inclusion criteriaa | Patients from HGC meeting both the inclusion and exclusion criteriaa |

|---|---|---|

| Indacaterol/formoterol9 | 165 (54.46) | <123 (40.59) |

| POET10 | 90 (29.70) | <67 (22.11) |

| SPARK11 | 70 (23.10) | <39 (12.87) |

| INVIGORATE12 | 48 (15,84) | <41 (13.53) |

| Fluticasone+vilanterol/ vilanterol13 | 90 (29.70) | <53 (17.49) |

| WISDOM14 | 70 (23.10) | <47 (15.51) |

| Crim C et al.15 | 90 (29.70) | <50 (16.50) |

| FLAME16 | 61 (20.13) | <31 (10.23) |

| SUMMIT17 | 13 (4.29) | <11 (3.63) |

| TRILOGY18 | 47 (15.51) | <24 (7.92) |

| Tie-COPD19 | 150 (49.50) | <104 (34.32) |

| TONADO20 | 182 (60.07) | <110 (36.30) |

| TRINITY21 | 47 (15.51) | <24 (7.92) |

| FULFIL22 | 106 (34.98) | 106 (34.98) |

| TRIBUT23 | 47 (15.51) | <29 (9.57) |

| DYNAGITO24 | 83 (27.39) | <67 (22.11) |

| IMPACT25 | 54 (17.82) | <44 (14.52) |

Some data, related to the described RCTs inclusion and inclusion criteria and their patients mean age, are described in Table 3, 4 and 5. Patients of HGC were significantly older than those participating in all of the referred trials.

RCTs inclusion and exclusion criteria and patients mean age.

| Study/referenceYear of publication | Indacaterol/Formoterol9(2010) | POET10(2011) | SPARK11(2013) | INVIGORATE12(2013) | Fluticasone+Vilanterol / Vilanterol13(2013) | WISDOM14(2014) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients... age (years); mean age | 63.064.0(median) | 62.8 (9.0) to62.9 (9.0) | 63.1 (8.0) to63.6 (7.8) | 40-9164.0 (Not reported) | 63.5 (8.8)to64.0 (9.3) | 63.8 (8.5) |

| Inclusion of never-smokers | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Inclusion if smoking amount < 10 pack/years | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Inclusion of GOLD stage I patients | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Inclusion referred to FEV1% | <80 and ...30 | ..± 70 | <50 | ...30 and <50 | ..± 70 | <50 |

| Inclusion if mMRC<2 or CAT<10 | Yes | Not reported | Not reported | Yes | Yes | Not reported |

| Inclusion of patients without previous ECOPD | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Exclusion if previous asthma | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Exclusion if current asthma | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Exclusion of patients in LTOT | No | Not reported | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Exclusion if Alfa-1-AT deficiency | No | Not reported | Yes | No | Yes | Not reported |

| Exclusion of malignancy / significant pulmonary comorbidities / unstable pulmonary disease | No | Not reported | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Exclusion if clinical bronchiectasis | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Exclusion of comorbidities** | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

RCTs, randomized controlled trials; mMRC, Medical Research Council Dyspnoea Questionnaire; CAT, COPD Assessment Test; LTOT, long-term Oxygen therapy; Alfa-1-AT, alfa-1-antitrypsin deficiency; * Mean age unless stated otherwise; **comorbidities, current significant disease which can influence the results of the studies or the patients... ability to participate in the trials.

RCTs inclusion and exclusion criteria and patients mean age (cont.).

| Study/referenceYear of publication | Crim C et al15 (2014; ref 16) | FLAME16(2016; ref 17) | SUMMIT17(2016; ref 18) | TRILOGY18(2016; ref 19) | Tie-COPD19(2017; ref 20) | TONADO20(2017; ref 21) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients... age (years); mean age | 63.6 (9.4)to63.8 (9.2) | 64.6 (7.8) | 65 (8) | 63.3 (7.9) to63.8 (8.2) | 63.9 (8.6)to64.2 (8.2) | 63.8 (8.3)to66.2 (8.0) |

| Inclusion of never-smokers | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Inclusion if smoking amount < 10 pack/years | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Inclusion of GOLD stage I patients | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Inclusion referred to FEV1% | ..± 70% | ...25 and <60 | >50 and ..±70 | <50 | ... 50 | < 80 |

| Inclusion if mMRC<2 or CAT<10 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Inclusion of patients without previous ECOPD | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Exclusion if previous asthma | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Exclusion if current asthma | yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Exclusion of patients in LTOT | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Yes |

| Exclusion if Alfa-1-AT deficiency | Yes | Yes | Notreported | Yes | Not reported | Not reported |

| Exclusion of malignancy / significant pulmonary comorbidities / unstable pulmonary disease | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Exclusion if clinical bronchiectasis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Notreported | Yes |

| Exclusion of comorbidities* | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Yes |

RCTs, randomized controlled trials; mMRC, Medical Research Council Dyspnoea Questionnaire; CAT, COPD Assessment Test; LTOT, long-term Oxygen therapy; Alfa-1-AT, alfa-1-antitrypsin deficiency; *comorbidities, current significant disease which can influence the results of the studies or the patients... ability to participate in the trials.

RCTs inclusion and exclusion criteria and patients mean age (cont.).

| Study/reference;Year of publication | TRINITY21(2017; ref 22) | FULFIL22(2017; ref 23) | TRIBUTE23(2018; ref 24) | DYNAGITO24(2018; ref 25) | IMPACT25(2018; ref 26) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients... age (years); mean age | 62.6 (8.9)to63.4 (8.7) | 63.9 (8.6) | 64.4 (7.7) to64.5 (7.7) | 66.3 (8.5)to66.5 (8.4) | 65.3 (8.3) |

| Inclusion of never-smokers | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Inclusion if smoking amount < 10 pack/years | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Inclusion of GOLD stage I patients | No | No | No | No | No |

| Inclusion referred to FEV1% | <50 | <80 | <50 | <60 | <80 |

| Inclusion if mMRC<2 or CAT<10 | No | No | No | Not reported | No |

| Inclusion of patients without previous ECOPD | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Exclusion if previous asthma | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Exclusion if current asthma | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Exclusion of patients in LTOT | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes (if ... 3L) |

| Exclusion if Alfa-1-AT deficiency | Yes | Not reported | Yes | Not reported | Yes |

| Exclusion of malignancy / significant pulmonary comorbidities / unstable pulmonary disease | Yes | Not reported | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Exclusion if clinical bronchiectasis | Yes | Not reported | Yes | Not reported | Yes |

| Exclusion of comorbidities* | Yes | No | Yes | Not reported | Yes |

RCTs, randomized controlled trials; mMRC, Medical Research Council Dyspnoea Questionnaire; CAT, COPD Assessment Test; LTOT, long-term Oxygen therapy; Alfa-1-AT, alfa-1-antitrypsin deficiency; *comorbidities, current significant disease which can influence the results of the studies or the patients... ability to participate in the trials.

When the inclusion criteria of the referred RCTs were applied to HGC, only a small portion of them could be eligible to participate in the referred trials, from 4.29% in the SUMMIT to 60.07% in the TONADO study. When both the inclusion and the exclusion criteria were applied, only as little as 3.63% in the SUMMIT, to as much as 40.59% in the study comparing formoterol to indacaterol were eligible to participate. The lack of representativeness of clinical trials in real patient populations seems to be common knowledge. In this study we quantify their magnitude in a local population of COPD out-patients followed in a medium-sized hospital. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study with such characteristics developed in a Portuguese population of COPD patients.

In the HGC study, 90 participants were never-smokers, or the smoking amount was < 10 pack/years, totalising 29.70% patients. They were not represented and could not benefit from the findings of 15 of the 17 referred studies. However, never-smokers can account for 31.7...45% of COPD patients in different studied populations,28,29 and a significant proportion of COPD patients around the world are known to be never-smokers.30 Nor were the findings applicable to 47 (75.80%) of the 62 women of HGC, again because they were never-smokers. It seems that the evidence from large RCTs is not applicable to never-smoking COPD patients. Asthma is a well-known risk factor for COPD, but because of the possibility of confusion between COPD and asthma, these patients are excluded from many RCTs.31 In the HGC 82 patients (27.42%) referred to a previous history of asthma under the age of 40, usually in childhood. The findings of nine of the 17 RCTs were not applicable to them. This matches previous papers.32 Twelve patients of HGC reported alfa-1-antitrypsin deficiency and 7, presenting a ZZ genotype, fulfilled criteria for augmentation therapy.33 They could not benefit from the evidence of at least eight RCTs. Thirty patients (9.90%) classified as GOLD stage I are represented in only one of the trials mentioned. Seventy COPD patients (23.10%) were classified as group A for therapeutic purposes. The findings of at least seven RCTs could not apply to them. The findings of eleven RCTs could also not apply to a significant number of the 45 patients benefiting from long-term oxygen therapy. From the 303 patients of HGC, 145 (47.85%) had not reported any ECOPD in the previous year. The findings of 12 of the 17 RCTs could not be applied to them. In the HGC the patients... mean ages were significantly higher than reported in all RCTs. The process of aging is often associated with an increased number of comorbidities and prescribed medication. It is well-known that there is a low rate of adverse effects when using inhaled medication in COPD patients. Nevertheless, by excluding patients with significant comorbidities, needing several chronic medications, RCTs promise a high rate of tolerability, which can be different in daily clinical practice. This may also change the way the results of RCTs apply to patients treated in routine clinical practice.

We acknowledge that the results of clinical RCTs will not be relevant to all COPD patients, and clinicians should select the patients to whom the results can be applied.32 However, a general lack of reliability must thus be assumed in the generalisation of conclusions from a significant number of RCTs to never-smokers, to patients with an asthma background, to patients suffering from alfa-1-antitrypsin deficiency, to patients GOLD stage I, to those not reporting previous exacerbations, and mainly to patients with significant comorbid conditions. Moreover, the inclusion criteria referred to by many RCTs significantly differ from normal clinical practice, where the ABCD assessment tool is usually used for therapeutic purposes.

Comparison with previous studiesOur findings agree with previous literature. In the respiratory field, as little as 5% of the target population was represented in the recruited populations of RCTs,34 Travers et al. demonstrated that only one in 20 patients with COPD, identified from a large general population survey in New Zealand, would have met the inclusion criteria for the major RCTs informing guidelines in COPD.35 Using data from a large European COPD primary care database, Kruis et al. found that 58...83 % of COPD patients in primary care would not serve as candidates for inclusion, in significant RCTs.36 Costa et al. related that only 7.4% of primary care patients could met the inclusion criteria used in 4 RCTs for allergic rhinitis, 6 and in a Norwegian study only a very small fraction of patients with asthma or COPD were shown to be represented in a typical clinical trial.4 A previous study,37 combining an extensive RCTs selection with a very representative COPD population, found that only around a quarter of community patients with COPD were eligible from RCTs participation.

Strengths and limitations of the studyThe present study was conducted by independent researchers, and the described RCTs were selected in a systematic manner. They have extensively contributed to the scientific evidence related to the treatment of COPD patients, and their conclusions are embodied in the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) report.

However, a significant number of exclusion criteria referred to by RCTs could not be identified in the HGC. In the HGC, there was no information related to established peripheral vascular disease and to diabetes mellitus with target organ disease. It was also not possible to specifically identify patients with established coronary artery disease and previous myocardial infarction, in the 148 patients referred to as suffering from heart disease. Because of that, only 13 patients of HGC (4.29%) meet the inclusion criteria of the SUMMIT study. The presence of a significant current disease, other than COPD, which can influence the results of the studies or the patients... ability to participate in the trials, was a common exclusion criterion, in many of the referred RCTs. However, it was not considered in the present analysis, because it was a very subjective issue. A clinical diagnosis of bronchiectasis was also referred as exclusion criteria in the majority of these studies. Likewise, it was not considered in the present analysis, because bronchiectasis... symptoms significantly overlap with those of COPD. Therefore, the number of patients who could benefit from the findings of these studies could be significantly lower.

Conversely, the HGC presented some specific characteristics that can partially justify the small fraction of patients that could benefit from the results of the referred RCTs: a significant rate of patients referring a previous history of asthma; the high prevalence of alfa-1-antitrypsin deficiency; the substantial number of individuals with low monthly income and low education level; a significant number of never-smokers COPD patients, mainly women, referring exposure to household air pollution from coal and biomass fuel combustion.

All of the referred above can significantly limit the generalisation of the results to other populations with different characteristics.

ConclusionsRandomised controlled trials are performed to provide a significant level of evidence on treatments efficacy. However, there is a significant lack of representativeness of RCTs in real populations of COPD patients. There is a need to complement the evidence provided by large RCTs, according to the extent to which their results, designed to target significant patients... populations, can be applied to typical patients treated in routine clinical practice. Pragmatic trials and other real-life studies must provide additional evidence about treatment effectiveness, in the heterogeneous populations of clinical practice.

Author contributionsDuarte-de-Ara..jo conceived and developed the study, carried out selection of bibliography, wrote the first draft and collaborated in the final writing. Pedro Teixeira carried out the statistical analysis and reviewed the final draft. Venceslau Hespanhol reviewed the final draft. Jaime Correia-de-Sousa reviewed all the drafts and collaborated in the final writing. All the authors approved the final manuscript.

FinancingThe authors have no financing to declare.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare regarding the present study.