The differential diagnosis of diffuse cystic lung diseases (DCLDs) includes a wide range of etiologies with different underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms.1,2 Although morphological features, such as shape, distribution within the lung parenchyma and adjacent structures, and the presence of other pulmonary manifestations may suggest a specific underlying disease, a significant overlap exists between tomographic findings from different etiologies. In these cases, a lung biopsy may be required to establish a diagnosis.1,2

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare slowly progressive neoplastic lung disease, which has a characteristic radiological appearance and affects mainly women of childbearing age. However, in women with regular and thin-walled cysts without extrapulmonary features compatible with LAM and with low levels of serum vascular endothelial growth factor D (VEGF-D), other potential rare etiologies may be included in the differential diagnosis, such as bronchiolitis, and smoking-related DCLDs.3–5 We present the cases of eight women that were initially suspected with LAM whose histopathological analysis was compatible with bronchiolitis.

Among 347 patients with DCLDs followed at our center since 2006, eight (2.3%) had diffuse pulmonary cysts on HRCT and a histological diagnosis of cellular and constrictive bronchiolitis and were assessed in this study. Clinical, functional, tomographic, and histological features were analyzed. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Pulmonary function tests adhered to recommended guidelines.6–8 Computed tomography was performed in a supine position. Quantification of the volume of the cystic lesions was obtained automatically by densitovolumetry using a computer program (Advantage Workstation Thoracic VCAR software; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WS, USA) and by selecting pixels between −1000 and −950 HU on soft tissue filter images. Paraffin blocks of lung tissue were retrieved for histological analysis (hematoxylin and eosin stain). Immunohistochemical staining for smooth muscle actin (SMA) and human melanoma black-45 (HMB-45) antibodies were examined.

Clinical and functional features at the time of lung biopsy are summarized in Table 1. All patients were non-smoking women with a mean age of 43±14 years at diagnosis. The most common symptom was dyspnea (75%). Four patients had a relevant exposure history. No patient had any relevant personal or family medical history. Anti-Sjögren syndrome-related antigen A/Ro or B/La antibodies, the rheumatoid factor, and antinuclear antibodies were negative. Serum inflammatory markers, and immunoglobulins were unremarkable.

Demographic, clinical and functional characteristics (n=8).

| Female | 8 (100%) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 43±14 |

| Time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis (years) | 2±2 |

| Current or former smokers | 0 |

| Environmental exposure | 4 (50%) |

| Previous (mold and birds) | 2 (25%) |

| Current (only birds) | 2 (25%) |

| Clinical manifestations at diagnosis | |

| Dyspnea | 6 (75%) |

| mMRC | 1 (0–1) |

| Cough | 4 (50%) |

| Wheezing | 1 (12.5%) |

| Pneumothorax | 1 (12.5%) |

| Pleuritic chest pain | 2 (25%) |

| Xerostomy | 2 (25%) |

| Xerophtalmia | 1 (12.5%) |

| Skin lesions | 0 |

| SpO2 on room air (%) | 97±2 |

| Oxygen use | 0 |

| Pulmonary function tests | |

| FVC (L) | 3.01±0.73 |

| FVC (%predicted) | 88±12 |

| FEV1 (L) | 2.32±0.85 |

| FEV1 (%predicted) | 79±23 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.73±0.14 |

| DLCO (mL/min/mmHg) | 18.2±4.6 |

| DLCO (%predicted) | 76±17 |

| Functional patterns | |

| Normal spirometry | 5 (63%) |

| Obstructive | 2 (25%) |

| Restrictive | 1 (12%) |

| Air trappinga | 2 (29%) |

| Reduced DLCO | 3 (38%) |

| Positive response to BDb | 1 (17%) |

Values are expressed as mean±SD, median (25th–75th percentiles) or n (%).

Definition of abbreviations: BD: bronchodilator; DLCO: carbon monoxide diffusing capacity; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in the first second; FVC: forced vital capacity; mMRC: modified medical research council dyspnea scale; SpO2: oxyhaemoglobin saturation by pulse oximetry.

Mean FEV1 and DLCO were 79±23% predicted, and 76±17% predicted, respectively. An obstructive pattern and reduced DLCO were found in 25% and 38% of patients, respectively.

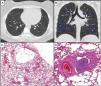

All patients showed diffusely distributed multiple, regular thin-walled cysts on HRCT (Fig. 1). Other tomographic patterns were not found. Four patients underwent HRCT to investigate respiratory symptoms while in the remaining, pulmonary cysts were incidentally found during an investigation of abdominal pain or a routine exam of the chest. The median tomographic extent of cysts was 2.51% (interquartile 25%–75%: 0.8%–8.9%). Serum VEGF-D levels were available for only two patients (139 and 407pg/mL).

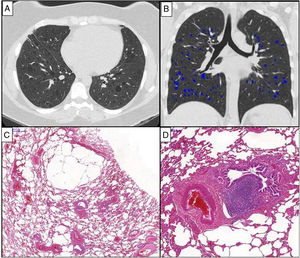

Chest HRCT scans (A and B) and histopathological findings (C and D) of a 38-year-old woman with chronic cellular bronchiolitis and diffuse cystic lung disease. (A) Axial CT image shows diffuse, regular, and thin-walled pulmonary cysts. The quantification of cystic lung lesions is depicted in blue (B). The percentage of the total lung area occupied with cysts is 2.75%. The photomicrographies (C and D) show mild inflammatory mononuclear cells infiltrating some of the bronchiolar walls. There are cystic alveolar changes in the nearby parenchyma tissue. Lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers are shown (hematoxylin and eosin stain) (D). Magnifications: C. ×13; D. ×70.

All patients underwent a surgical lung biopsy. Histological analysis showed evidence of chronic cellular (Fig. 1) or constrictive bronchiolitis. Six cases had inflammatory mononuclear cells infiltrating the bronchiolar wall with a patchy distribution and variable intensity. Biopsies of two patients displayed infrequent, poorly formed and randomly distributed non-necrotizing granulomas. Two patients presented bronchiolar fibrosis. One patient had a discreet fibrotic thickening of the submucosa associated with luminal narrowing in some small airways, whereas another patient displayed complete focal obliteration of the bronchiolar lumen with fibrous scar formation. All patients presented with parenchymal cysts characterized by airspace distensions in the centrilobular and subpleural regions. The walls of these lesions contained residual alveolar tissue. Proliferation of immature smooth muscle-like cells was not detected.

DCLDs have a broad differential diagnosis. Clinical and tomographic findings combined with a multidisciplinary approach make differentiation of various entities possibile. In our study, we described eight women with DCLDs referred with an initial suspicion of LAM. Following a histopathological analysis they were diagnosed as having cellular or constrictive bronchiolitis, with mild severity, which is a very rare etiology for DCLD. Although suggestive, the tomographic patterns of the diffuse, regular and thin-walled cysts in women are not specific to LAM.2,4,5 In the absence of definite findings, a pulmonary biopsy is mandatory to diagnose LAM.3 Low availability of serum VEGF-D dosage is a limitation of our study.

Some findings on HRCT contribute to establishing the etiology of DCLDs. In pulmonary Langerhans histiocytosis, cysts are usually irregular, predominate in the upper and middle lung zones and may be associated with nodules.1,2 In Birt-Hogg-Dubé (BHD) syndrome, cysts are multiple, thin-walled and predominantly basilar and paramediastinal.1,2 Cysts in lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia occur in the lower lobes along the peribronchovascular bundle, frequently with ground-glass opacities.2

The typical pathological and immunohistochemical features of LAM were not identified in our study. Histologically, LAM nodules consist of two cellular subpopulations: the spindle cells express SMA and forms the core of the nodules surrounded by epithelioid cells that exhibit immunoreactivity for HMB-45 antibody.9 On histopathology, the morphology of BHD cysts may resemble what was found in our cases. However, we excluded BHD based on clinical and tomographic features.10 Cysts, emphysema, and respiratory bronchiolitis are identified in smoking-related DCLDs, but were not found in our study.5 A combination of the DCLDs and small airway disease is mainly identified in specific conditions, such as Sjögren’s syndrome, and it is thought that chronic small airway damage might lead to cyst formation in these patients. A possible explanation for the lung cyst formation in bronchiolitis is a check-valve obstruction with distal airspace overinflation related to air trapping, distal to the abnormal airways.1,2

In two cases, histological analysis showed evidence of chronic cellular bronchiolitis associated with infrequent, poorly formed, non-necrotizing granulomas, frequently seen in hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP). Pulmonary cysts have been described in HP possibly due to partial bronchiolar obstruction.2

Potential etiologies for our patients with bronchiolitis include autoimmune disorders, such as Sjögren syndrome, post viral infections and HP. However, none of the etiologies raised were confirmed.

In summary, LAM is a prototypical DCLD with a characteristic appearance on HRCT. However, cystic features alone are inadequate to establish a diagnosis of LAM. In such context, bronchiolitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of DCLDs.

Informed consentPatients gave informed consent for this study.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.