Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (IPPFE) is a recently described rare entity, characterized by pleural and subpleural parenchymal fibrosis and elastosis mainly in the upper lobes. The etiology and pathophysiology are unknown. The prognosis is poor, with no effective therapies other than lung transplantation. IPPFE should be properly identified so that it can be approached correctly. This report describes two clinical cases with clinical imaging and histological features compatible with IPPFE.

Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (IPPFE) is a rare condition characterized by fibroelastotic thickening of the pleural and subpleural lung parenchyma, mainly in the upper lobes.1 This entity was first mentioned in English-language medical literature by Frankel et al.2 in 2004, although the same concept designated as idiopathic pulmonary upper lobe fibrosis was proposed in 1992 by Aminati et al.3 There is little known about its etiology and most cases are considered to be idiopathic, although a few cases are believed to occur in a familial/genetic lung disease context2 and others have been reported in association with previous bone marrow transplantation.4 New data have been published suggesting that recurrent infections may have a role in its pathogenesis.5 Recently IPPFE was recognized as a specific rare idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) in the update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the IIPs6; IPPFE was characterized by an elastotic fibrosis present with an intra-alveolar fibrosis.6 High-resolution chest tomography (HRCT) shows dense subpleural consolidation with traction bronchiectasis, architectural distortion, and upper lobe volume loss.6 The authors present two cases of IPPFE in which the final diagnosis was obtained after CT-guided transthoracic core lung biopsy.

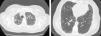

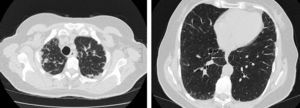

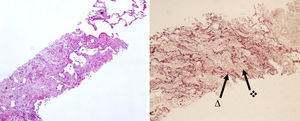

Case report 1The patient was a 66-year-old female, caucasian, nonsmoker, had worked as art gallery assistant, had a history of esophageal hiatus hernia and was chronically medicated with omeprazole. She had no known family history of pulmonary disease. In September 2010, she complained of dyspnea on exertion and nonproductive cough, with progressive worsening. The patient was examined by a general practitioner and a chest X-ray was performed that revealed a reticular densification with peripheral distribution and predominance in the upper lobes. Lung function tests were as follows: FVC 1.74L (79.4% predicted), FEV1 1.51L (83.5% predicted), FEV1/FVC 86.8%, TLC 4.16L (95.2% predicted), DLco 2.85mL/min/mmHg (44.6% predicted). Blood gas parameters were in the reference range values. She walked 450m at 6-min walk test (6-WT) with an oxygen desaturation of 12% (initial SatO2-97% and final SatO2-85%). HRCT images showed pleural and subpleural thickening with fibrotic changes in the marginal parenchyma, mainly in the upper lobes (Fig. 1). A short course of corticosteroids was prescribed with no clinical improvement. The patient was then referred to the Interstitial Lung Disease outpatient clinic. On chest examination, fine bibasilar inspiratory rales were identified. Autoimmune serological testing was negative. A bronchoscopy was performed with no noticeable airways abnormalities. Bronchoalveolar lavage revealed a lymphocytosis (28.4%) with a very high CD4/CD8 ratio (14.5), and no microorganism or malignant cells were identified. Transbronchial and bronchial biopsies had no evidence of malignancy or granulomas. The patient underwent a CT-guided transthoracic core lung biopsy in two distinct locations, complicated by pneumothorax with bronchopleural fistula and subcutaneous emphysema. Histological evaluation showed marked thickened visceral pleura and prominent predominantly elastic sub-pleural fibrosis with mild, patchy lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate; orcein stain showed that the elastosis was within the alveolar walls, marking the intra-alveolar fibrosis (Fig. 2). Despite the prescription of azathioprine (2mg/kg/day), the patient is clinically and functionally worse after 20 months of follow-up: FVC 1.63L (82% predicted), FEV1 1.44L (89% predicted), FEV1/FVC 89.5%, TLC 3.28L (80% predicted), DLco 1.66mL/min/mmHg (26% predicted).

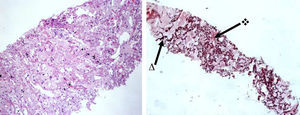

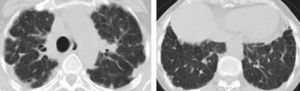

The patient was a 59-year-old female, caucasian, nonsmoker, accountant, with history of pulmonary tuberculosis (5-years-old), post-infectious bronchiectasis, recurrent respiratory infections, and osteoporosis. The patient had no known family history of pulmonary disease. Since the age of 50 she had attended a respiratory outpatient clinic because of dyspnea on exertion and pleural thickening in the upper lobes. These findings were interpreted as within the clinical picture of sequelae of tuberculosis and the patient was medicated with an inhaled association of budesonide and formoterol. However, after 7 years of follow-up, the patient presented a worsening of dyspnea on exertion and dry cough. On chest examination, fine bibasilar inspiratory rales were identified. Chest X-ray revealed a linear densification with peripheral distribution and predominance in the upper lobes, with significant worsening compared to previous ones. HRCT showed a pleural thickening with associated subpleural fibrosis, mainly in the upper lobes (Fig. 3). Autoimmune serological testing was negative. Lung function tests showed moderate restrictive ventilatory impairment and a significant decrease in diffusion capacity: FVC 1.37L (56.1% predicted), FEV1 1.17L (57.3% predicted), FEV1/FVC 85.5%, TLC 2.87L (64.7% predicted), DLco 2.07mL/min/mmHg (29.4% predicted). Blood gas parameters were in the reference range values. She walked 435m at 6-WT with an oxygen desaturation of 10% (initial SatO2-96% and final SatO2-86%). A bronchoscopy was performed with no noticeable airways abnormalities. Bronchoalveolar lavage revealed neutrophilic (53.8%) and eosinophilic (14%) alveolitis and no microorganism or malignant cells were identified. CT-guided transthoracic core lung biopsy was then performed with iatrogenic pneumothorax. Histological evaluation showed marked thickened visceral pleura and sharply demarcated elastic fibrosis, without significant inflammation; orcein stain showed elastosis of the alveolar walls with a predominant intra-alveolar fibrosis (Fig. 4). Treatment was started with 400mg/day of hydroxychloroquine and 7.5mg/day of prednisolone. At the time of writing, after a 10-month follow-up period, the patient is clinically and functionally stable: FVC 1.27L (54% predicted), FEV1 1.07L (54% predicted), FEV1/FVC 84.4%, TLC 2.94L (68% predicted), DLco 1.52mL/min/mmHg (22% predicted).

This report describes two cases in which clinical presentation, imaging, and histopathological features are compatible with IPPFE. The recent update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the IIPs recognizes IPPFE as a specific rare IIP.6

A review of the available data shows that these two patients were older than the reported median age of 57 years at diagnosis.5 However, the absence of smoking habits is in line with the previous reports.1,2,5

There is little information and insufficient knowledge regarding the etiology of IPPFE and most cases are considered idiopathic, although a few cases have underlying diseases or conditions such as collagen vascular diseases, bone-marrow transplantation,4 or lung transplantation.7 Genetic predisposition is probably another factor. Frankel et al. reported two cases believed to have familial/genetic lung disease.2 Reddy et al. reported that just over half of the patients studied had recurrent lower respiratory tract infections and speculated that repeated inflammatory damage in a predisposed individual may lead to a pattern of intra-alveolar fibrosis with septal elastosis (IAFE).5 In fact, the second case described in this manuscript has a history of recurrent respiratory infections.

There is a certain variability of clinical presentation among the reported IPPFE patients, such as spontaneous pneumothorax, dyspnea, or chronic cough. However, in a recently published series of clinical cases,5 the most frequent presentation symptoms were shortness of breath in 91.7% and dry cough in 50% of the patients, which fit in with the complaints mentioned by the patients reported in this paper.

Computed tomography findings in both cases revealed bilateral pleuroparenchymal thickening, which was mostly marked in the upper zones, with an associated subpleural reticular pattern consistent with fibrosis. These findings are also consistent with previous series described in literature.1,2,5

In both cases, CT-guided transthoracic lung biopsies were made in upper lobes and demonstrated IAFE. The transition between the fibroelastosis and the underlying normal lung parenchyma was abrupt. However, there is no standard histological criterion for the diagnosis of IPPFE. Reddy et al., using published histological criteria, characterized them as “definite” when there was upper zone pleural fibrosis with subjacent intra-alveolar fibrosis accompanied by alveolar septal elastosis.5 Kusagaya et al. used the pathological criteria for the diagnosis of IPPFE as follows: intense fibrosis of the visceral pleura; prominent, homogeneous, subpleural fibroelastosis; sparing of the parenchyma distant from the pleura; mild, patchy lymphoplasmocytic infiltrates, and presence of small numbers of fibroblastic foci.8 IAFE is not specific to IPPFE, being a pathway of lung injury common to a variety of disorders.5 A multidisciplinary approach, integrating all clinical, imaging and histopathological findings led to an IPPFE diagnosis in both cases.

Published case series1,5,8 have included patients who were submitted to surgical lung biopsy. However, considering that the two described cases were already complicated by iatrogenic pneumothorax, the risk of performing this procedure was very high. Becker et al. postulate that these patients may be prone to the development of secondary spontaneous pneumothorax and reported a death following a surgical lung biopsy complicated by a large bronchopleural fistulae.9 Since the histological features obtained by CT-guided transthoracic core lung biopsy were considered representative and compatible with the diagnosis of IPPFE (after exclusion, in a multidisciplinary discussion, of apical cap, the most frequent differential diagnosis), it was decided not to carry out a surgical biopsy.

There is no defined treatment and the therapeutic approach varies greatly and is largely empirical in the published clinical cases, with some of them reporting aggressive treatment with corticosteroids and immunosupressants.5 Based on this report, we also considered this therapeutic approach with the first patient diagnosed with IPPFE. However, since the hypothesis of recurrent respiratory infections as a possible etiology of this disease had been described and increasingly considered likely, we decided on a different option for the second patient with the prescription of hydroxychloroquine and a low dose of corticosteroids.

There is more recognition of the etiology and physiopathology of IPPFE, however it would be important for us to know more about the efficacy of different therapeutics administered so far and the evolution of the patients.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.