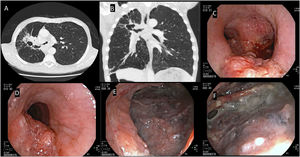

A 61-year-old male, ECOG-PS scale 2, smoker, who was homeless and had no medical history, presented to the emergency department with breathlessness at rest, yellow sputum and hoarseness. Thoracic computed tomography revealed centrilobular emphysema and a right hilar mass (79 × 39 mm) invading the mediastinum, associated with irregularity in the calibre of the right main bronchus (RMB). Flexible bronchoscopy showed an infiltrative lesion at the entrance of the RMB extending into the main carina and upper third of the left main bronchus (LMB). Also, a wide fistula at the RMB with approximately 2 cm in diameter was noted (Fig. 1), providing visualization ofthe ipsilateral lung parenchyma. Bronchial biopsies of the infiltrative lesions at the main carina and LMB evidenced squamous cell lung carcinoma, PD-L1 50–60%. TNM staging was T4N2M1a (pleural invasion). Considering patient's general status and clinical condition, he was started on palliative treatment with pembrolizumab. The patient died one month after starting immunotherapy due to post-obstructive pneumonia with associated septic shock.

(A, B) Chest CT (A-axial; B-coronal): centrilobular emphysema and right cavitated hilar mass (79×39 mm) associated with irregularity in the calibre of the right main bronchus (RMB) and main carina. (C, D) Flexible bronchoscopy: Infiltrative lesion at the entrance of the RMB extending into the posterior wall of the main carina and upper third of the left main bronchus. (E) Lung parenchyma view at the entrance of RMB - RMB fistula with approximately 2 cm in diameter. (F) Distal view at the RMB.

This is a case of main bronchus fistula in the context of mediastinal invasion by a large cavitated squamous cell carcinoma. A main bronchus fistula with endobronchial visualisation of the lung parenchyma and its bronchi is a rare condition in the absence of prior surgery and dehiscence.1 Additional concern should be addressed to potential problems associated with these fistulas, namely the risk of bacterial colonisation/infection, pulmonary flooding and pneumothorax.2,3

Oncological treatment of lung cancer may play an important role in preventing bronchial fistula enlargement. However, bronchial fistulas may worsen following specific oncological treatments. In addition to clinical conditions as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hypoalbuminemia or liver cirrhosis, radiotherapy stands out as the oncological treatment with the greatest potential to promote the occurrence or enlargement of bronchial fistulas. This risk seems dose-dependent and greater for doses higher than 5.000Gy.3 Neoadjuvant treatment with chemotherapy and/or immunotherapy is also an established risk factor for postoperative bronchial fistula.4-6 Although uncommon, pembrolizumab monotherapy also has the potential to cause or worsen bronchial fistulas, which occurred in 1 of 300 patients assessed in an analysis of real-world data.7 It is therefore imperative to provide close clinical and imaging follow-up of these patients and, whenever indicated, to consider interventional bronchology or referral to a specialised thoracic surgery team.

Ethical considerationsWritten informed consent was obtained from this patient.

Funding informationNone.

Consent from all authorsAll authors reviewed and agreed to submit this manuscript.