Elastic tubing was recently investigated as an alternative to the conventional resistance training (RT) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The effects of RT on the mucociliary system have not yet been reported in the literature.

ObjectiveThe aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of two RT programs on mucociliary clearance in subjects with COPD.

MethodsTwentyeight subjects with COPD were randomly allocated by strata, according to individual strength of lower limbs, to defined groups: conventional resistance training (GCT) or resistance training using elastic tubing (GET). Nineteen subjects (GET: n=9; GCT: n=10) completed the study and were included in the analysis. The measurement of vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate and respiratory rate), lung function (spirometry) and the primary outcome mucociliary clearance analysis (saccharin transit time test (STT)) were performed before and after the 12 weeks of RT.

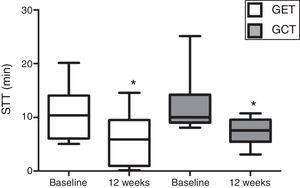

ResultsIn relation to the mucociliary transportability analysis, no differences were observed between the baseline evaluations of the training groups (p=0.05). There was a significant reduction in the STT values in both training groups, GET (10.64±5.06 to 6.01±4.91) and GCT (12.07±5.10 to 7.36±2.54) with p=0.03. However, no differences between groups were observed on the magnitude of SST changes after interventions (GET: −43.51%; GCT: −38.94%; p=0.97).

ConclusionThe present study demonstrated that both RT with elastic tubing and conventional training with weights promoted similar gains in the mucociliary transportability of subjects with COPD.

Peripheral muscle dysfunction is a prevalent condition in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Common features include reduced muscle strength and endurance, muscle atrophy and poor oxidative capacity.1 This muscle dysfunction is directly related to exercise intolerance, impaired health-related quality of life2 and involves increased use of health care resources.3

In addition to peripheral muscle dysfunction subjects with COPD may present impairment in mucociliary clearance, an essential mechanism of pulmonary defense. Mucociliary clearance removes inhaled particles and microorganisms from the respiratory tract.4,5 Dysfunction of this mechanism causes hypersecretion leading to lung infections and exacerbations.4,5

The efficiency of mucociliary clearance can be analyzed by the velocity of nasal mucociliary transport (MCT) and is well correlated with tracheobronchial transport6,7 which requires more invasive procedures to assess. MCT is measured using substances with a characteristic flavor, for example, the saccharin transit time (STT).6–9 STT test has been widely reported in previous studies as being simple, valid and reliable with similar results to those obtained with the use of radioisotope particles for MCT analysis.6,10

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) in subjects with COPD is supported by the highest-level of evidence.11 Resistance training (RT) is an important component in improving muscle strength, activities of daily living and functional exercise capacity and reducing fatigue and dyspnea symptoms.1,12,13

RT protocols routinely include weight machines and free weights in standard proposals, however elastic tubing (ET) was recently investigated as an alternative to the conventional RT for subjects with COPD. Studies with elastic devices have demonstrated similar benefits to conventional training14–17 with the added advantage of being portable, and inexpensive.14,17 The linear increase of resistance occurring in ET is less harmful to the joints, and provides a greater recruitment of motor units when compared to the conventional resistance training.18 This is particularly interesting for patients with muscle dysfunction like COPD.

There is evidence that aerobic exercise improves the mucociliary system by altering the viscosity of nasal mucus, thus can be recommended as an adjunctive treatment to respiratory physiotherapy techniques.4,19,20 This type of exercise increases the levels of adrenergic mediators that contribute to changes in mucociliary clearance during or after exercise.21 Although the effects of RT on mucociliary system have not yet been reported, it is reasonable to hypothesize that it has a positive influence on mucociliary clearance as RT modulates changes in the autonomic control in subjects with COPD.22

Knowing the effects of RT on MCT in subjects with COPD is essential for health professionals involved in pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD. MCT is the first line of defense of the respiratory system against aggressor agents and irritants. The maintenance of its integrity, therefore, is necessary to reduce the risk of respiratory infections and hospitalizations in COPD.4,19 Furthermore, such knowledge could lead to strategies to improve mucociliary clearance in subjects with COPD. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of two RT programs on mucociliary clearance in subjects with COPD.

MethodsDesign of the studyInitially, subjects referred to an outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation program were screened for inclusion in this randomized, parallel group, clinical trial. COPD diagnosis was made according to internationally accepted criteria.18 Patients included should be clinically stable (i.e. absence of exacerbation in the month before inclusion) and have quit smoking for at least one year prior to the inclusion. Subjects were excluded if they presented nasal trauma or deviated septum, unstable severe cardiac disease or musculoskeletal disorders that hindered the implementation of the experimental protocol. Recruitment and follow-up of individuals was conducted between 2014 and 2015 in a specialized rehabilitation center in Presidente Prudente, São Paulo, Brazil. This clinical trial (RBR-7KCR2P) was approved by the local ethics committee (CAAE: 12492113.5.0000.5402) and all included subjects provided written consent form.

Twenty-eight subjects were randomly allocated to one of the two a priori defined groups: Conventional RT (GCT) or RT using elastic tubing (GET). The randomization was performed by strata,23 where subjects were classified into quartiles according to individual strength of lower limbs (i.e. isometric maximum voluntary contraction of the knee extensors). Subjects in each quartile were numbered in brown envelopes and randomized into one of the 2 groups, by a researcher unrelated to the study.

Although therapists and subjects were not blinded for the interventions, data analysis was performed by a researcher who was not involved with the data collection.

This study is part of a major project, with knee extension strength defined as primary outcome (data not shown). Sample size calculation was done based on an equivalence study. Twenty patients (10 per group) were needed to achieve a power of 80%, expecting a difference of 45N between groups with a standard deviation of 36N and taking into account a typical dropout rate of 20%.

The evaluations were performed before and after the 12 weeks of RT. The initial evaluation took place in two days. On the first day the identification and measurement of vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate and respiratory rate) and lung function (spirometry) were performed. To confirm abstinence from smoking, the carbon monoxide concentration of the expired air was measured (COex). On the second day of the protocol, the mucociliary transport analysis via the saccharin transit time test (STT) was performed. Details of all the assessments are provided below. To determine initial workload of training groups, the repetition maximum (RM) test was performed on each subject on the first day of training protocols.

Pulmonary function testPulmonary function was measured prior to the protocols of training by means of simple spirometry (MIR-Spirobank v3.6, Italy) in accordance with the standards of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS).24

Measurement of hemodynamic parametersRespiratory rate was measured by observing the number of expansions of the rib cage, watching the respiratory mechanics of the individual for 1min. Heart rate was determined using a heart rate monitor (Polar S810i, Finland). The auscultation method was used to measure the blood pressure in the left arm, using an aneroid sphygmomanometer and stethoscope (BD, Brazil). All vital signs were collected after 20min of initial resting.

Measurement of nasal mucociliary transport (saccharin transit time)The evaluation of mucociliary transport was done via the assessment of SST, prior to the start of training and after a minimum of 48h upon completion of the final training session, following the measurements of hemodynamic parameters. Subjects were seated with their heads over-extended at 10°. The SST test was initiated by introducing 250μg of granulated saccharin through a plastic straw, under visual control, approximately 2cm into the right nostril. Subjects were instructed not to walk, talk, cough, sneeze, scratch or blow their nose, and to swallow a few times per minute until they felt a flavor in their mouth; at which point the patient immediately gestured to the examiner and the time was recorded. The subjects were instructed not to use drugs, such as anesthetics, barbiturates, analgesics, anxiolytics and antidepressants and to avoid alcoholic or caffeine-based substances for a minimum of 12h prior to the measurement.25

Training protocolBoth groups followed the training programs for 12 weeks (3 times per week), totaling 36 training sessions of approximately 60min duration. At the beginning and at the end of each session, vital signs were verified and stretching of the trained muscle groups was carried out. For each RT exercise a RM test was performed (using elastic tubing in the GET and using conventional weight machine in the GCT). Familiarization to the exercises took place prior to the start of training on each separate visit.

Training was performed in a periodized and progressive form.15 The distribution of the dynamics of the training conducted for the GET and GCT groups were as follows: Training conducted according to the dynamics of the exercise: 1st to 3rd weeks: 2×15 RM; 4th to 6th weeks: 3×15 RM; 7th to 9th weeks: 3×10 RM; 10th to 12th weeks: 4×6 RM.

The repetition maximum (RM) testThe RM test was used for both groups to determine initial workload as well as progression over the sessions and it was performed at the beginning of each session. Participants performed the RM test to verify the maximum number of repetitions they could do with a given load. The load would be maintained for that session when the maximum number of repetitions performed was (according to the dynamics of the exercise) ±2, it would be otherwise adjusted to achieve the expected number of repetitions23, thus with the 1st week: 15 RM (15±2 repetitions), 7thweek: 10 RM (10±2 repetitions) until 12th week: 6 RM (6±2 repetitions). The load was adjusted (via increase/decrease of weight in GCT and via change of tube resistance in GET) until resistance permitted 15 repetitions.

RT with elastic tubingElastic tubing was used for the training in the GET. Different tubes with progressive resistance were used in such a way that the higher the reference number, the higher the diameter (and hence, the resistance) of the tube (#200, #201, #202, #203 and #204, Lemgruber©, Brazil26). Exercises were performed using a specific chair that had an elastic tubing support fitting for each trained muscle group.15

Additionally, metal rings, beams (plastic cable ties) to fix the elastic tubing to the rings were used. Based on a pilot study (unpublished data) we defined the initial selection of tube diameter for each movement using subjects’ dynamometry. The initial lengths of the tubing were determined according to the individual's distance from the upper or lower limb to the hook (fixed point) on the chair. Thus, the length of the tubing used for each patient was unique and remained the same for all sessions. Trained muscle groups were the same as those evaluated during dynamometry.

Conventional resistance trainingThe weight machine equipment (Ipiranga®, Brazil) was used for the training of both upper and lower limb muscle groups. Simple pulley exercises were performed for elbow flexion, shoulder flexion and abduction (upper limbs), and a single-leg knee extension and flexion (lower limbs) in each session. Determination of load and training progression were a priori defined to be identical to the elastic tubing group. The training protocol followed the same method as the protocol described in the GET.

Statistical analysisA statistical package (SPSS v.22, SPSS Inc., USA) was used for data analysis. Normal distribution of the data was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The results are presented as mean values±standard deviations or as median [interquartile range 25–75%] according to the data distribution. ANOVA for repeated measures model in two-factor scheme was performed for each group to compare training effects. Data used for the repeated measurements was checked for violation of sphericity using the Mauchly test. The Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used when the sphericity was violated. Between groups comparisons for both baseline and training changes (Δ=baseline−12 weeks) were performed using the Student t test for independent samples (or Mann–Whitney test for nonparametric data). Categorical variables (training frequency) were analyzed using the chi-square test. The significance level was set at p<0.05.

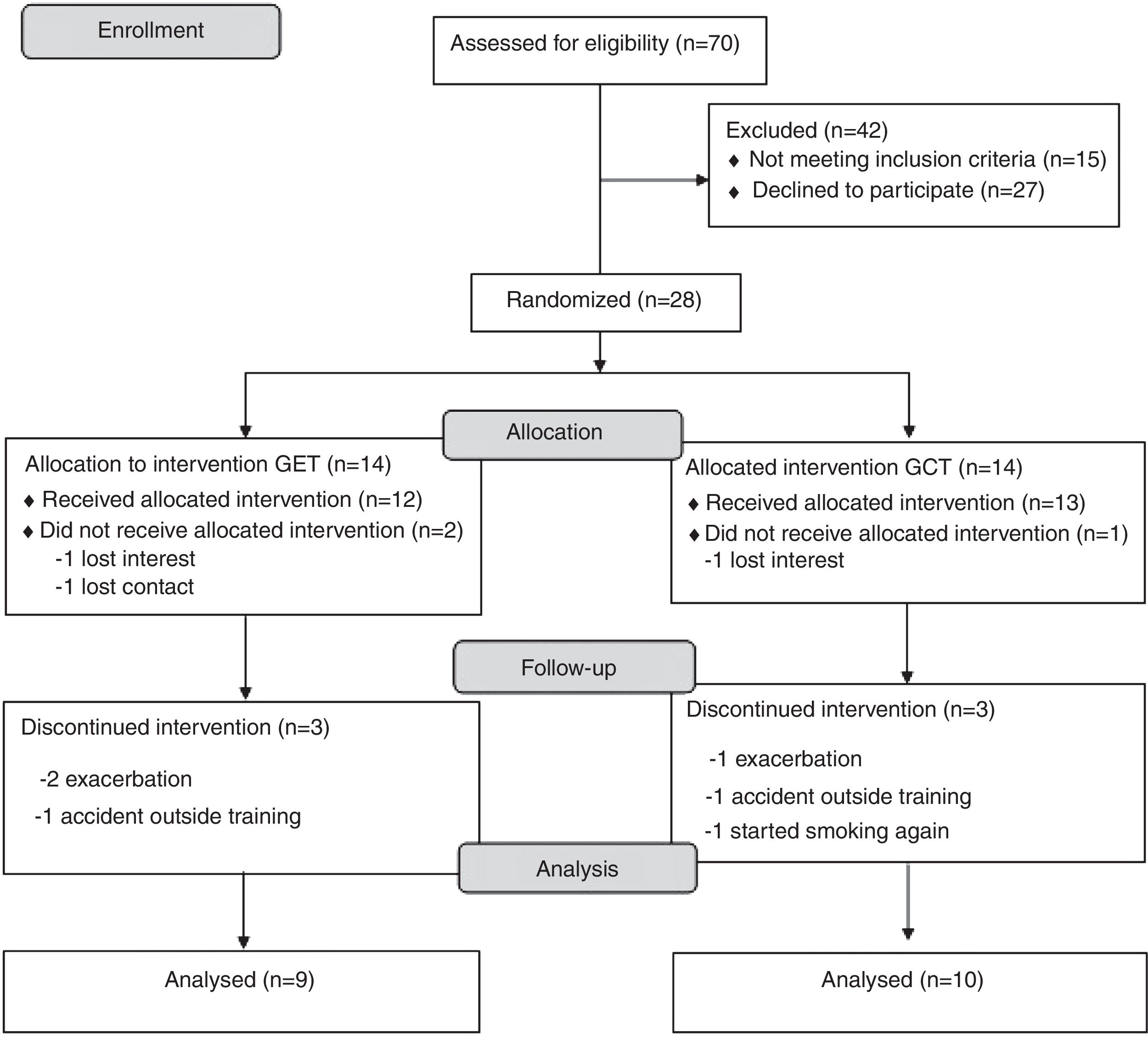

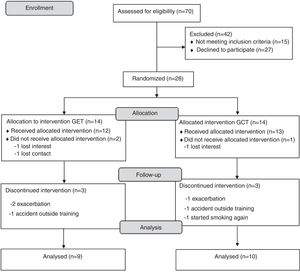

ResultsA complete overview of the study can be seen in Fig. 1. Twenty-eight subjects with COPD were included and allocated to one of the two groups. Nine subjects quit the study after randomization (three withdrew consent and six dropped out during the training). Eventually 19 subjects completed the study and were included in the analysis (convenience sample). All subjects completed more than 75% of training frequency, with no differences between groups (p>0.05).

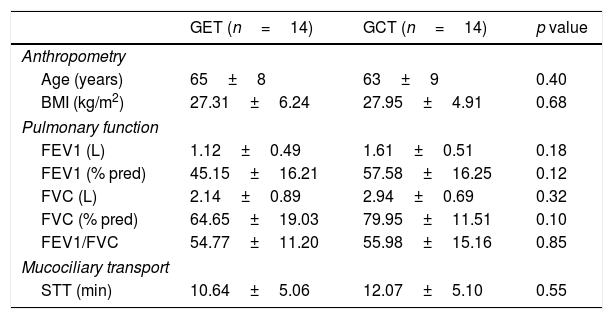

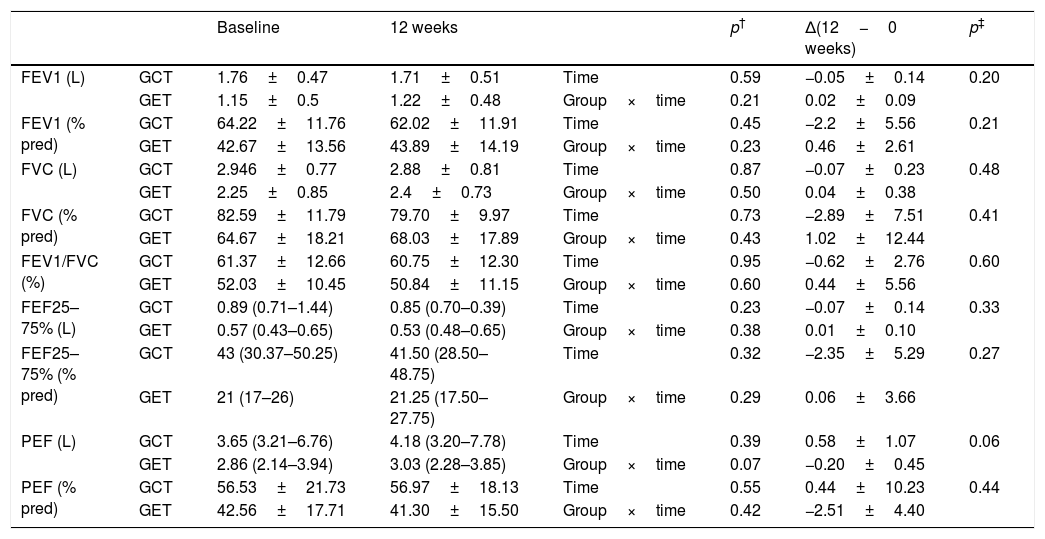

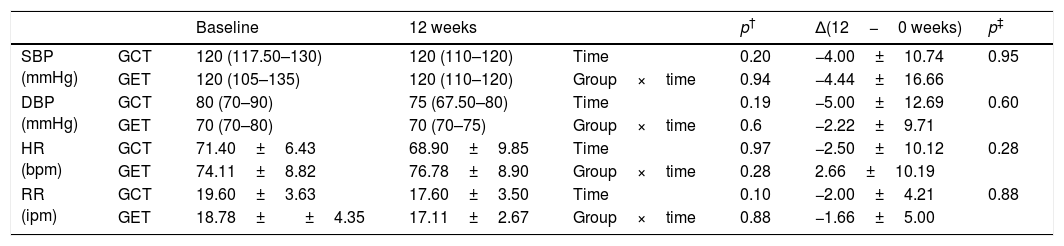

Table 1 presents the sample characterization. No significant differences were found between the groups in any of the investigated outcomes at baseline. Lung function remained unchanged after interventions in both groups (Table 2) and the analysis of hemodynamic parameters showed a similar magnitude of changes between the two training groups (Table 3).

Anthropometric, pulmonary function and mucociliary transport of the evaluated groups, expressed as mean and standard deviation.

| GET (n=14) | GCT (n=14) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometry | |||

| Age (years) | 65±8 | 63±9 | 0.40 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.31±6.24 | 27.95±4.91 | 0.68 |

| Pulmonary function | |||

| FEV1 (L) | 1.12±0.49 | 1.61±0.51 | 0.18 |

| FEV1 (% pred) | 45.15±16.21 | 57.58±16.25 | 0.12 |

| FVC (L) | 2.14±0.89 | 2.94±0.69 | 0.32 |

| FVC (% pred) | 64.65±19.03 | 79.95±11.51 | 0.10 |

| FEV1/FVC | 54.77±11.20 | 55.98±15.16 | 0.85 |

| Mucociliary transport | |||

| STT (min) | 10.64±5.06 | 12.07±5.10 | 0.55 |

GET, training with elastic tubings and GCT, conventional; BMI: body mass index; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC: forced vital capacity; STT: saccharin transit time.

Comparison of spirometric values before and after physical training (GET (n=9), training with elastic tubings and GCT (n=10), training with weight equipment).

| Baseline | 12 weeks | p† | Δ(12−0 weeks) | p‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1 (L) | GCT | 1.76±0.47 | 1.71±0.51 | Time | 0.59 | −0.05±0.14 | 0.20 |

| GET | 1.15±0.5 | 1.22±0.48 | Group×time | 0.21 | 0.02±0.09 | ||

| FEV1 (% pred) | GCT | 64.22±11.76 | 62.02±11.91 | Time | 0.45 | −2.2±5.56 | 0.21 |

| GET | 42.67±13.56 | 43.89±14.19 | Group×time | 0.23 | 0.46±2.61 | ||

| FVC (L) | GCT | 2.946±0.77 | 2.88±0.81 | Time | 0.87 | −0.07±0.23 | 0.48 |

| GET | 2.25±0.85 | 2.4±0.73 | Group×time | 0.50 | 0.04±0.38 | ||

| FVC (% pred) | GCT | 82.59±11.79 | 79.70±9.97 | Time | 0.73 | −2.89±7.51 | 0.41 |

| GET | 64.67±18.21 | 68.03±17.89 | Group×time | 0.43 | 1.02±12.44 | ||

| FEV1/FVC (%) | GCT | 61.37±12.66 | 60.75±12.30 | Time | 0.95 | −0.62±2.76 | 0.60 |

| GET | 52.03±10.45 | 50.84±11.15 | Group×time | 0.60 | 0.44±5.56 | ||

| FEF25–75% (L) | GCT | 0.89 (0.71–1.44) | 0.85 (0.70–0.39) | Time | 0.23 | −0.07±0.14 | 0.33 |

| GET | 0.57 (0.43–0.65) | 0.53 (0.48–0.65) | Group×time | 0.38 | 0.01±0.10 | ||

| FEF25–75% (% pred) | GCT | 43 (30.37–50.25) | 41.50 (28.50–48.75) | Time | 0.32 | −2.35±5.29 | 0.27 |

| GET | 21 (17–26) | 21.25 (17.50–27.75) | Group×time | 0.29 | 0.06±3.66 | ||

| PEF (L) | GCT | 3.65 (3.21–6.76) | 4.18 (3.20–7.78) | Time | 0.39 | 0.58±1.07 | 0.06 |

| GET | 2.86 (2.14–3.94) | 3.03 (2.28–3.85) | Group×time | 0.07 | −0.20±0.45 | ||

| PEF (% pred) | GCT | 56.53±21.73 | 56.97±18.13 | Time | 0.55 | 0.44±10.23 | 0.44 |

| GET | 42.56±17.71 | 41.30±15.50 | Group×time | 0.42 | −2.51±4.40 |

Data expressed as mean and standard deviation or median and median and interquartile range of 25–75%. Δ(12−0 weeks): difference between (final minus initial evaluations).

Comparison of hemodynamic parameters before and after physical training (GET (n=9), training with elastic tubings and GCT (n=10), training with weight equipment).

| Baseline | 12 weeks | p† | Δ(12−0 weeks) | p‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP (mmHg) | GCT | 120 (117.50–130) | 120 (110–120) | Time | 0.20 | −4.00±10.74 | 0.95 |

| GET | 120 (105–135) | 120 (110–120) | Group×time | 0.94 | −4.44±16.66 | ||

| DBP (mmHg) | GCT | 80 (70–90) | 75 (67.50–80) | Time | 0.19 | −5.00±12.69 | 0.60 |

| GET | 70 (70–80) | 70 (70–75) | Group×time | 0.6 | −2.22±9.71 | ||

| HR (bpm) | GCT | 71.40±6.43 | 68.90±9.85 | Time | 0.97 | −2.50±10.12 | 0.28 |

| GET | 74.11±8.82 | 76.78±8.90 | Group×time | 0.28 | 2.66±10.19 | ||

| RR (ipm) | GCT | 19.60±3.63 | 17.60±3.50 | Time | 0.10 | −2.00±4.21 | 0.88 |

| GET | 18.78±±4.35 | 17.11±2.67 | Group×time | 0.88 | −1.66±5.00 |

Data expressed as mean and standard deviation or median and median and interquartile range of 25–75%. Δ(12−0 weeks): difference between (final minus initial evaluations); SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HR: heart rate; RR: Respiratory rate; mmHg: millimeters of mercury; bpm: beats per minute; ipm: incursions per minute.

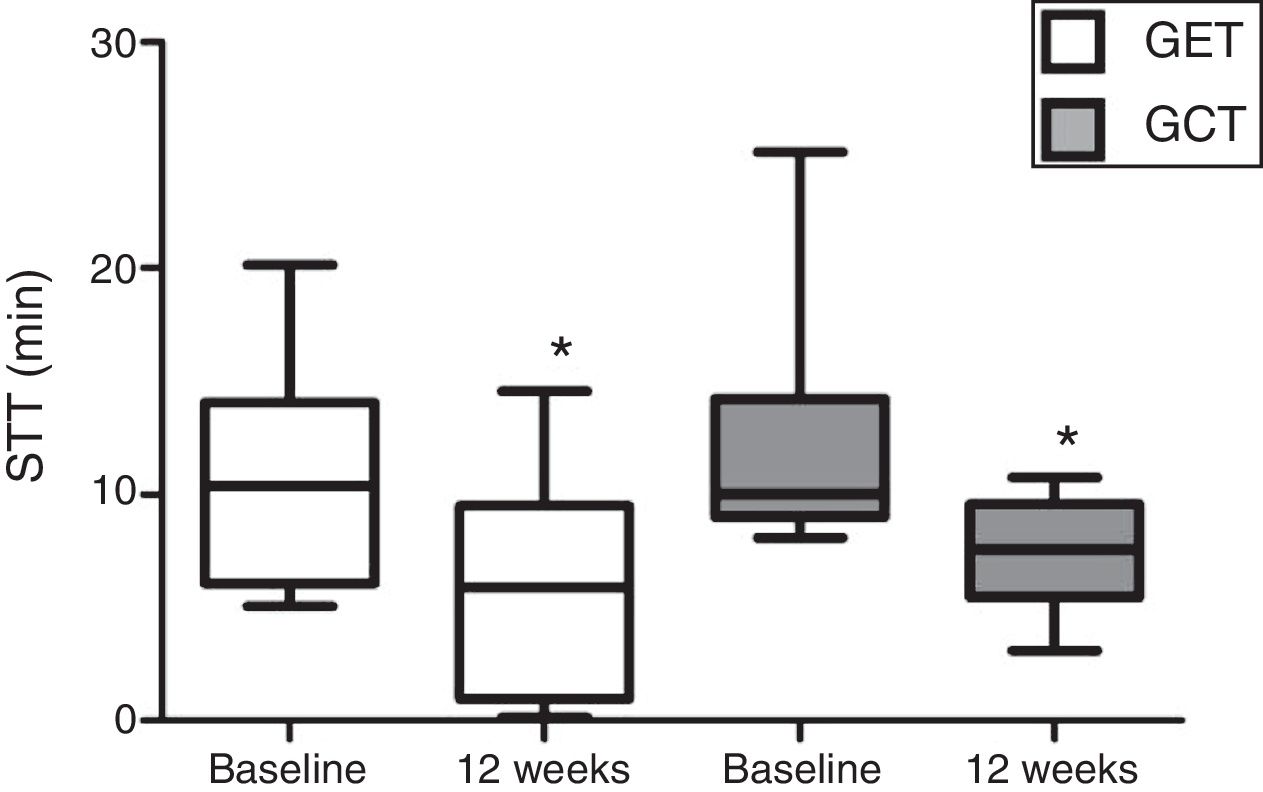

In relation to the MCT analysis, no differences were observed between the baseline evaluations of the training groups (p>0.05). There was a significant reduction in the SST values after 12 weeks in GET and GCT (p=0.03) (Fig. 2), but no interaction between type of training and SST decrease (p=0.97) and no differences between groups were observed on the magnitude of SST changes after interventions (p=0.97).

Comparison of the mucociliary transportability values before and after resistance training of 12 weeks. Data expressed as mean and standard deviation. STT: saccharin transit time; GET: training with elastic tubings; GCT: training with weight training equipment; *: significant difference between initial and final evaluation (p=0.03).

The results of this study indicate significant improvements in MCT after RT in subjects with COPD in both conventional method (weight training), and the elastic tubing method. This is the first study up until now to analyze the effects of RT on the mucociliary system of subjects with COPD.

It has been shown that physical exercise is essential for improving airway clearance of subjects with COPD. It is particularly important as the dysfunction of this mechanism causes hypersecretion leading to lung infections and exacerbations and hospitalization.4,5,8

Few studies in the literature investigated the chronic effects of exercise on MCT. Leite et al. were the only ones to investigate the chronic effect of exercise on MCT in patients with COPD.27 They observed that MCT did not change after 12 weeks of aerobic training. Similarly, Salh et al. performed 8 weeks of aerobic training in patients with cystic fibrosis and concluded that aerobic training had no effect on mucociliary clearance, using an indirect measurement of MCT (i.e. amount of mucus expectoration).19

Essentially exercise induces an increase in the autonomic nervous system activity, release of adrenergic mediators, increases ventilation and respiratory rate, which causes an increase in the velocity of MCT. These phenomena occur consistently in different populations (i.e. athletes aged between 18 and 37 years,28 smokers and nonsmokers with an average age of 40 years29). Furthermore, two cross-sectional studies,30,31 have pointed out that for individuals with normal lung function, MCT is more efficient in physically active individuals than in those insufficiently active. The chronic effects of regular exercise, however, remain unclear.

It is believed that the improvement in MCT observed in the present study may be related to the behavior of the autonomic nervous system after a period of RT. There is evidence that the autonomic function is impaired in COPD and that exercise has positive effects on it.32,33 RT induces an overall improvement in the parasympathetic and sympathetic components of the autonomic nervous system.34,35 Underlying mechanisms of autonomic improvement in these subjects after RT are yet to be clarified. Factors such as the reduction in circulating norepinephrine may be attributed to this improvement.

Additionally, it is important to mention that there were similar improvements in the peripheral muscle strength between the groups (data not shown). Due to the important relation between muscle strength and autonomic function in subjects with COPD,36 it could be hypothesized that improvements in muscle function are partly responsible for the improvements in the autonomic nervous system. Since the mucociliary system is regulated by the autonomic nervous system,37 it is believed that the possible improvement in autonomic modulation could influence improved MCT values.

Another hypothesis for the improvements in MCT is related to low-grade chronic inflammation. Most of the subjects included in the study were ex-smokers. It is known that the toxic substances released by the cigarette promote local inflammation in the respiratory tract,38,39 causing damage that can affect mucociliary function.40 When smokers give up there can be reversibility of mucociliary function after 15 days of abstinence from smoking.41 However, when COPD is present, the chronic low-grade inflammation could impair this reparative process. As RT is able to decrease the proinflammatory profile of subjects with COPD,16 we speculate that the anti-inflammatory “millie” generated by chronic exercise training may help in some way to repair the mucociliary function of these subjects. Future studies are warranted in this area to clarify the possible associations between the outcomes of chronic exercise and MCT in COPD.

The reduced sample size and absence of a control group may be considered limitations of the study. With the limited sample, it was not possible to verify differences in subgroups of subjects according to COPD severity. Further studies investigating this specific issue are warranted. Another limitation would be that we did not include the effects of RT on outcomes such as cough and sputum, since both are related to MTC.4,5 However, it is important to note that the data presented in this study are secondary analyzes of a larger project which presents other variables demonstrating the effects of training with elastic tubing.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that both RT with elastic tubing and conventional training promoted similar gains in the mucociliary transportability of subjects with COPD. Future research needs to approach the chronic effects of exercise on mucociliary clearance in subjects with COPD, in order to clarify the physiological mechanisms that influence this process.

FundingThis study was supported by the National Council of Scientific Researches (CNPq) [Grant number: 470742/2014-3]. BSAS is funded by CAPES/Brazil.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.