The COVID-19 pandemic crisis, among so many social, economic and health problems, also brought new opportunities. The potential of telemedicine to improve health outcomes had already been recognised in the last decades, but the pandemic crisis has accelerated the digital revolution. In 2020, a rapid increase in the use of remote consultations occurred due to the need to reduce attendance and overcrowding in outpatient clinics. However, the benefit of their use extends beyond the pandemic crisis, as an important tool to improve both the efficiency and capacity of future healthcare systems. This article reviews the literature regarding telemedicine and teleconsultation standards and recommendations, collects opinions of Portuguese experts in respiratory medicine and provides guidance in teleconsultation practices for Pulmonologists.

Since its definition and first implementation initiatives at the end of the last century, the practice of telemedicine has had the potential to have a positive impact on healthcare services and health outcomes in many ways. COVID-19 and the need to reduce attendance and overcrowding in outpatient clinics led to several changes in the care and organisation of Pulmonology services. Portugal has seen a rapid increase in the use of remote consultations.

Remote consultations have proved important in reducing pressure on health services and improving access to non-COVID patients – and this is an important lesson. Although teleconsultations cannot fully replace face-to-face consultations, evidence shows that they can achieve equivalent patient outcomes while improving patient satisfaction.1,2 Looking to the future, in a pandemic-free scenario, teleconsultations appear as a cost-effective and efficient way to enable access to routine care for chronic respiratory patients and should be incorporated, as an additional tool, in the medical care of these patients.

Nevertheless, as telemedicine and teleconsultation programmes pose unquestionable advantages in improving healthcare's efficiency, their implementation is far from optimization. Significant limitations in terms of overall guidance, both scientific and organizational, threaten their appropriate delivery. This is especially relevant in chronic respiratory diseases, as the heterogeneity of clinical conditions and patient journeys’ steps demand specific guidelines.

This article reviews the literature regarding telemedicine and teleconsultation standards and recommendations, collects opinions of Portuguese experts in respiratory medicine and provides guidance in teleconsultation practices for Pulmonologists.

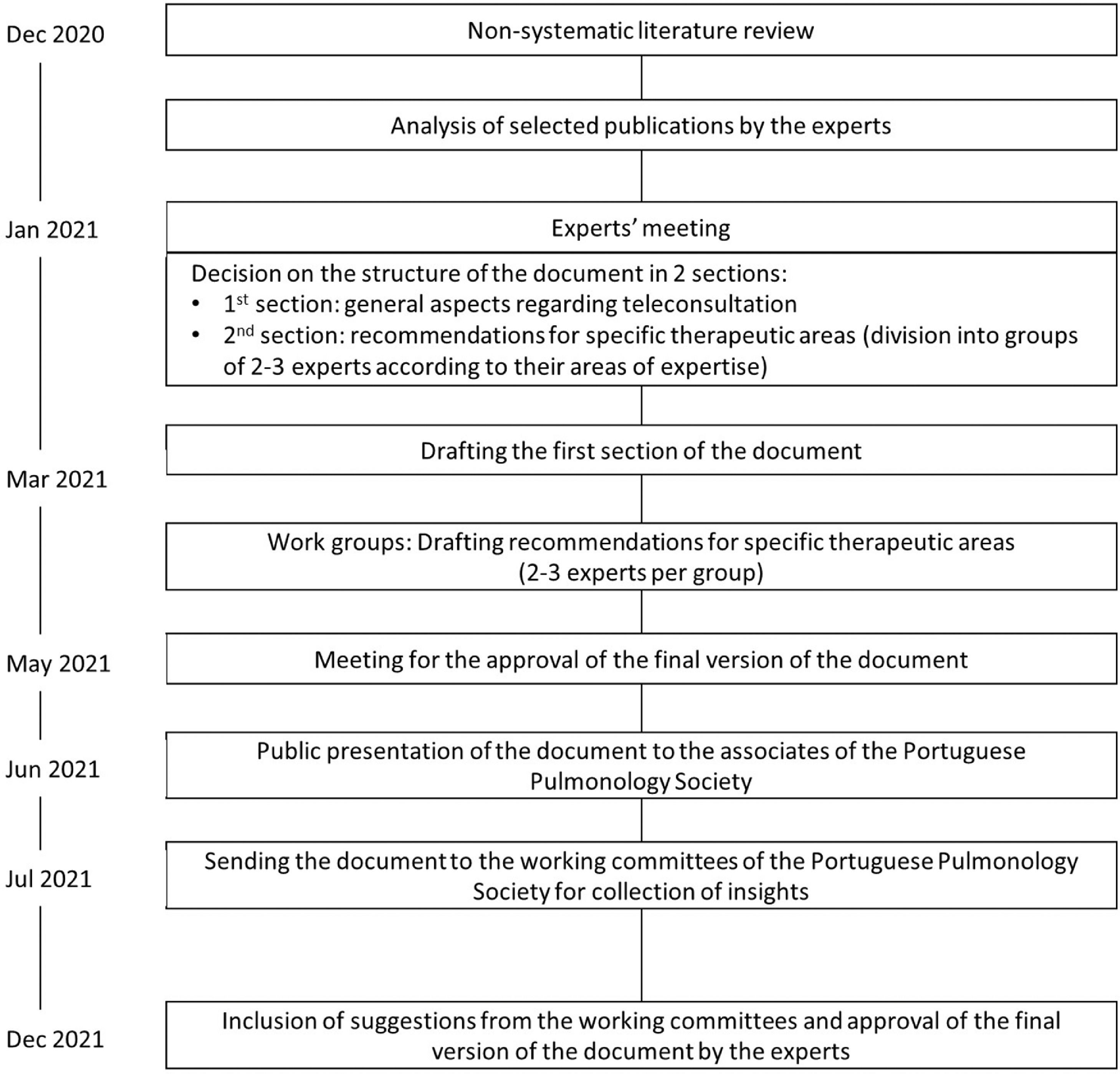

MethodologyA narrative non-systematic literature search of MEDLINE/Pubmed database was conducted in December 2020 using the keywords “telemedicine”, “telehealth”, “telemonitoring”, “teleconsultation” and “video consultation”. Also, other international and national societies were searched on this topic as well as documents from Portuguese authorities regarding legal issues and implementation. Other references were proposed by the authors throughout the preparation of the document and added to the final references.

Three meetings with all authors took place between January and June 2021.

The methodology applied for the elaboration of this document is shown in Fig. 1.

Telemedicine's definition and frameworkDefinitionTelemedicine, according to its first nomenclature reconciliation by the World Health Organization, was defined as “the delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health care providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities”.3

More recently, from a more operational perspective, telemedicine has been seen as the “distribution of health services in conditions where distance is a critical factor, by health care providers that use information and communication technologies to exchange information useful for diagnosis where a doctor is able to perform diagnosis at distance”4, having the potential of mediating patients’ contact with specialised care consultants.5 Although a broader concept of telehealth has been argued,4,6,7 for the purposes of this paper, ‘telemedicine’ and ‘telehealth’ are used interchangeably. There are core elements in telemedicine that must always be respected7:

- -

its purpose of providing clinical support;

- -

its intention to overcome geography issues, connecting patients to healthcare professionals in different locations;

- -

its practice including the use of information and communication technologies;

- -

its goal of improving health outcomes.

In Portugal, telehealth has been perceived as a core part of digital transformation strategies in health by addressing geographic inequalities and improving access to healthcare, thus improving the health system's effectiveness and efficiency.6 Indeed, good outcomes and promising local and regional strategies have been reported in our country.8,9

Furthermore, general standards for the legal practice of teleconsultations in Portugal have been established,10 including: respecting the doctor-patient relationship, ultimately not to be replaced by teleconsultations; ensuring the independence of physicians, who shall follow this practice when a good clinical overview of the patients’ condition is deemed possible; and ensuring that the physician has quality, complete, and sufficient information through teleconsultation to make a medical decision. In addition, a governmental guidance was released in 2015, focusing on teleconsultations between different healthcare institutions, with the objective of improving access to a specialised healthcare team even across long distances. That guidance falls outside the scope of this document as it applies to forms of doctor-doctor interaction where clinical cases of patients are discussed.

Telemedicine in clinical practice: teleconsultationsTelemedicine enables doctors and other healthcare providers to assist their patients beyond physical limitations as it encompasses a spectrum of diverse technologies and applications.11

Recently, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been applied to medical care, not only in improving remote healthcare, in developing algorithms to match the availability of healthcare providers to patients, but even going beyond the doctor-patient relationship.12,13 Examples of this are AI-based machine learning methods, which may even eventually replace clinical judgment.14 Several questions and concerns have been raised, namely ethical, legal, and privacy issues.13 These new forms of digital healthcare are beyond the scope of this paper and will not be addressed here.

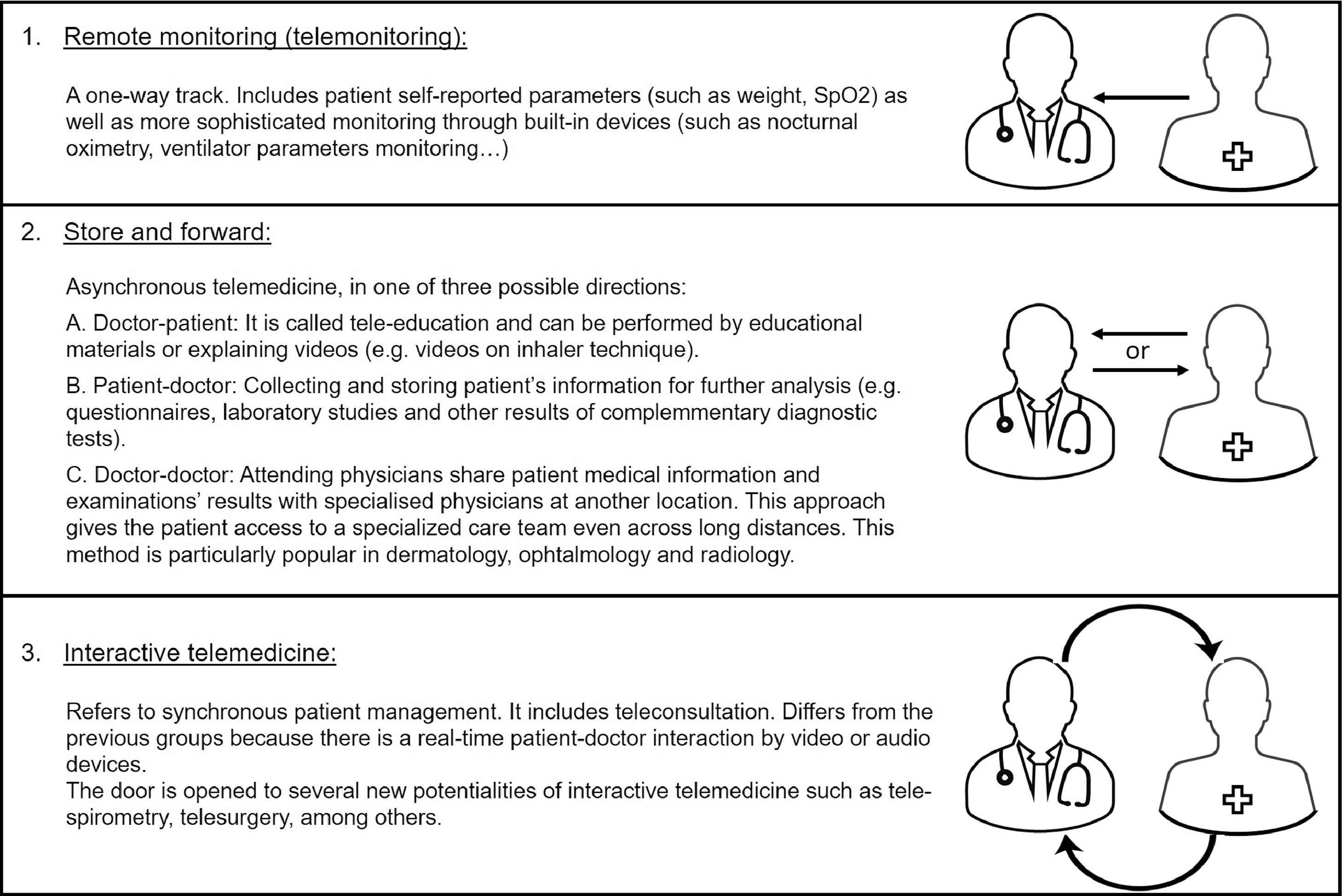

The different modalities of telemedicine can be grouped in three categories (Fig. 2).15

Three categories of telemedicine.15 This figure is an original image created by the authors for this publication.

We will focus on teleconsultation,16 defined as consultation in which information and communication technologies are implemented in order to overcome geographical and functional distances,17 carried out through video and/or audio.

Teleconsultation is only a small part of telemedicine. However, teleconsultations imply that some of the other strategies are already in place. For example, in a patient with chronic respiratory failure under home non-invasive mechanical ventilation, a teleconsultation is only appropriate where telemonitoring is already happening - not only reporting adherence and ventilatory efficacy parameters, but also real-time monitoring, such as night-time oximetry and/or oxy-capnography. Home care providers have been playing a key role in this type of support, but wireless monitoring systems linked to hospital systems are now also available.

There is still a long way to go in the context of telemedicine. And this great boost that teleconsultation has had in the last year can definitely enhance the development of other potentialities of telemedicine.

It is of utmost importance to stress that the use of information and communication technologies in health should always safeguard the security of information, ensuring data privacy and confidentiality. Thus, only platforms that respect these conditions should be used.

Advantages of teleconsultationTeleconsultations make it possible to assess, diagnose, and treat patients remotely. These take place using one of two main approaches: remote patient–doctor contact while the patient remains at home; or the patient going to a local clinic or hospital, where other healthcare providers mediate the contact with a consultant physician. The latter is indicated in clinical conditions in which a clinical and/or biometric physical evaluation is required. Both approaches encompass several advantages,6,18–21 such as:

- •

increasing access to specialists regardless of their national distribution;

- •

improving articulation between different physicians and levels of care of the health system, namely by facilitating the communication between hospital physicians and general practitioners;

- •

gains in care effectiveness, coupled with gains in comfort, time, and travel costs for patients;

- •

supporting long-term home management of specific chronic health conditions;

- •

reducing infections associated with healthcare services due to less crowded waiting rooms.

With regard to minimising infectious risks, critical during the pandemic of COVID-19, telehealth was established in a systematic review as very appropriate for reducing disease transmission and overall morbidity and mortality.22 It has been argued that the pandemic led to the development of more “sophisticated” telemedicine, by simplifying processes and reducing unnecessary complexity,23 although consensus practices remain to be established.24

Teleconsultation's limitationsExamples of good outcomes of telemedicine have been published, namely in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease – COPD.25 However, teleconsultations are not suitable for all patients and for all clinical situations.26 From a technological perspective, it is important to ensure adequate technical infrastructures (phone, computer, internet connection, as appropriate)27 and carefully keep in mind that “technology should always be adapted to the patient and not the reverse”.25 The transition to teleconsultation, with its related bureaucratic processes, at least at the beginning, does not seem to minimize consultation time. From a clinical perspective, some conditions are not adequately managed by teleconsultation,26–28 and some objectives of consultation may not be achieved with this modality.27 Finally, only clinicians duly trained in teleconsultation should perform it,29 and practices shall be standardised, compliant, and regulated.28

Video and audio-teleconsultationsVideo consultations have shown some advantages over audio (telephone) consultations,26 such as more personal contact between health professionals and patients,26,30,31 although strong evidence of their effectiveness is still lacking.24 These consultations are generally suitable for:

- •

younger patients (< 65 years), with good digital literacy in the technological solution used;

- •

follow-up consultations for clinically stable patients where a full physical exam is not expected to be necessary (as video consultations allow some parts of a physical examination to be performed). First consultations and consultations due to new symptoms should only be considered in very specific and well-defined clinical circumstances;

- •

situations where the video is the preferred method for both clinician and patient.

On the other hand, telephone (audio) consultations tend to be shorter and have a more restricted patient disclosure of health problems than face-to-face consultations.30 These consultations may generally be appropriate for:

- •

older patients (≥ 65 years) and/or those with poor digital skills in complex technological solutions;

- •

settings where complex video call setup and/or technical infrastructures for video consultation are unattainable;

- •

consultations aimed at addressing simple health concerns by the patient or the physician;

- •

follow-up of clinically stable patients in which a physical examination is not necessary;

- •

situations in which a teleconsultation is deemed appropriate by both clinician and patient, and telephone is their preferred method.

Finally, there are specific situations that should exclude the possibility of a teleconsultation,27,28 such as:

- •

presence of acute respiratory symptoms;

- •

new complications of underlying diseases;

- •

consultations where severe prognostic circumstances are expected to be addressed;

- •

or consultations where decompensation of underlying diseases cannot be correctly established.

In the field of Pulmonology, the use of telemedicine has been proposed and reported in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, interstitial lung diseases (ILD), chronic respiratory failure (CRF), and home mechanical ventilation (HMV), among other clinical situations.32 Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, there were some validated tools and scales for remote assessments in respiratory medicine.33 More than 50% of pulmonologists rated the importance of telemedicine as “high” or “very high”,34,35 with potential for better care in chronic respiratory diseases such as asthma and COPD.28

After the COVID-19 pandemic, teleconsultation will still have a place in the future of respiratory medicine. Our view is mirrored by other publications, whose authors have recognised the incorporation of new technologies into new models of care as the key to the future success of Pulmonology.23 Moreover, teleconsultation is seen as an important tool to improve both the efficiency and capacity of future healthcare systems,35 and the potential for greater control and care in chronic respiratory diseases has been acknowledged.28

Considering teleconsultation in respiratory diseases, this document will address:

- •

general issues, including patient suitability and selection.

- •

specific issues, related to each respiratory disease.

From a general perspective, we find that it is important to highlight some essential principles for the correct implementation of teleconsultation in respiratory diseases – Table 1.

Main eligibility criteria are common to the different respiratory diseases.36 The particularities regarding specific diseases will be described below.

Inclusion Criteria

- •

Adults (≥ 18 years) with a diagnosis of respiratory disease, with a suspected or diagnosed sleep-disordered breathing, or referred for smoking cessation;

- •

Verbal or written consent to perform the teleconsultation;

- •

Availability and familiarity with a suitable device - phone, mobile phone, tablet or computer;

- •

Patients already followed by the department.

Exclusion Criteria

- •

Current exacerbation or clinical instability requiring urgent physical examination;

- •

Physical or cognitive impairment that makes the teleconsultation unfeasible.

- •

First consultations for smoking cessation and sleep-disordered breathing may be suitable, as described below.

- •

Follow-up consultations and hospital discharge follow-up consultations should be considered, respecting individual plans of care for each patient according to the disease and clinical condition. Renewal of therapy plans for medication and oxygen or ventilation therapies is a clear indication for teleconsultation.

- •

An unscheduled consultation shall be considered if there is a need by the patient to have an additional consultation related to his/her condition. In this case, there should be an assessment of the situation through teleconsultation, and, if it is not possible to adequately resolve the problems, a face-to-face consultation should be proposed and scheduled.

- •

Another potential use of teleconsultation is as initial screening of acute situations for chronic respiratory patients in home care, to better decide between a home visit or a face-to-face consultation in the hospital.

Guidance regarding respiratory tele-rehabilitation, given its own specificities, falls outside the scope of this document and will be described elsewhere.

In this document, we discriminate the disease-specific criteria for each of the follow-up consultations in the different respiratory diseases.

However, the preparatory steps apply to all of them, and are described below.

These recommendations only apply to follow-up consultations.

1. Guidance steps

- •

Asthma Control Test (ACT) / Control of Allergic Rhinitis and Asthma Test (CARAT)

- •

Peak expiratory flow meter, if applicable

- •

Pulse oximeter, if available

- •

Inhalers to explain inhaler technique (if video consultations) or pre-recorded videos on specific inhalers

- •

Electronic prescription system

These recommendations only apply to follow-up consultations.

1. Guidance steps

- ■

mMRC Questionnaire

- ■

COPD Assessment Test (CAT) Questionnaire

- ■

Pulse oximeter, if available

- ■

Inhalers to explain inhaler technique (if video consultations) or pre-recorded videos on specific inhalers

- ■

In patients with non-invasive ventilation, access to ventilator reports (adherence and ventilation parameters); to nocturnal oximetry and/or nocturnal oxi-capnography and diurnal recording of end-tidal or transcutaneous CO2

- ■

Electronic prescription system

These recommendations apply to follow-up teleconsultations in patients diagnosed with lung cancer who have undergone previous curative surgery and do not require additional treatment beyond adjuvant therapy.

There are, however, some anecdotal lung cancer cases that can be considered after a long course of stability without treatment requirement, although that orientation should be validated by an accurate evaluation and decision from the multidisciplinary team meeting.

Apart from lung cancer, incidental pulmonary nodules follow-up requires serial chest CT evaluation and is guided by algorithms, posing a particular indication for teleconsultations.

1. Guidance steps

- ■

ECOG Performance Status Scale/ Karnofsky Performance Status Scale

- ■

Pulse oximeter, if available

- ■

Electronic prescription system

These recommendations apply to smokers who want to make a serious attempt to quit smoking and who have been referred to a Pulmonology clinic for assessment. First-time and follow-up consultations, unscheduled consultations, and end of follow-up consultations should be considered. We reinforce that first-time teleconsultations should be video consultations.

1. Guidance steps

First consultation

Follow-up consultation

- •

Unscheduled consultation

If there is a need to review treatments, their duration and adverse events, if there is a relapse, or in case of vital situations that require close monitoring.

- •

End of follow-up consultation

At 12 months after starting treatment, if there has been abstinence for more than 6 months, no craving, and absence of significant weight gain (< 3-4 Kg) or psychological diseases or distress.

- •

Visual Analogue Scale on motivation to quit smoking

- •

Richmond test

- •

Fagerström test

- •

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- •

Smoker behavioural profile evaluation

- •

Electronic prescription system

First consultations and follow-up consultations should be considered for patients with sleep disorders.

Follow-up teleconsultations in sleep medicine are highly dependent on telemonitoring, not only in terms of adherence, but mainly for checking efficacy parameters. No follow-up teleconsultation should occur without the PAP device report. Other telemonitoring options may be suitable, such as nocturnal oximetry under PAP treatment.

1.Guidance steps

First consultation

Follow-up consultation / Checking the results of diagnostic tests

- ■

Epworth sleepiness scale

- ■

Sleep diary

- ■

PAP report prepared by the provider company or obtained through built-in wireless connectivity

- ■

Electronic prescription system of home respiratory care

Follow-up teleconsultations may be considered for patients with suspected or diagnosed Nocturnal Hypoventilation Syndrome. This also applies to neuromuscular patients, depending on the speed of disease progression and clinical judgement.

Patients who require previous evaluation to start non-invasive ventilatory support are not suitable for teleconsultation. Also, patients of high complexity (e.g. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis) or highly ventilator-dependent may require a face-to-face assessment, a home visit, or a scheduled hospital admission.

Considering the potential role of the caregiver, physical or cognitive impairment should not be regarded as exclusion criteria for teleconsultation.

1. Guidance steps

- •

Questionnaires (SRI / S3-NIV)

- •

Pulse oximeter

- •

Ventilator reports prepared by the home care provider or obtained through built-in wireless connectivity. Ventilatory parameters – minimum requirements: compliance (including graph with hours of use), programmed ventilatory parameters, trend graph and / or measurement of leakage, AHI, % triggered breaths pressure, flow and alarm management

- •

Access to monitoring tools of ventilation efficacy – nocturnal oximetry and/or oxi-capnography

- •

Electronic prescription system of home respiratory care

Interstitial Lung Diseases (ILDs) encompass a range of distinct diseases with substantial differences in their underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, therapeutic approach, and prognosis.

Regardless of ILD, all consultations during the diagnostic approach should be done face-to-face until the diagnosis is fully established at the Multidisciplinary Team meeting. Thereafter, diseases such as sarcoidosis or some smoking-related disorders (e.g. respiratory bronchiolitis associated with ILD), which often have a stable clinical course and do not need any significant therapeutic intervention, are much more suitable for teleconsultation. In contrast, in all other ILDs that require complex therapeutic interventions, such as immunosuppressants and antifibrotic agents, or have a more unstable clinical course with risk of progression, patients need to be assessed in person. Therefore, the modality of the consultation will depend on the nature of the disease and the particularities of the drugs prescribed.

1. Guidance steps

- ■

mMRC Questionnaire

- ■

Visual Analogue Scale

- ■

Leicester Cough Questionnaire (Chronic Cough Quality of Life Questionnaire)

- ■

Pulse oximeter

- ■

Electronic prescription system

The pandemic crisis of COVID-19, amongst so many social, economic and healthcare problems, also brought new opportunities. It has allowed other forms of contact to be explored and has accelerated the digital revolution. And great steps have been taken towards a true implementation of telemedicine.

Teleconsultation, initially performed out of a great need to not loose contact with patients, but in a very empirical way, now appears as another tool at our disposal. This document seeks to establish recommendations to standardise the practice of this telemedicine modality.

Teleconsultation is just the beginning in the digital revolution in healthcare. In a near future, it is expected that other, more complex modalities of telemedicine will also become part of daily clinical practice.

It can never be emphasized too strongly that technology should always be at the service of the patient, and not the other way around. All these emerging tools only make sense if they prove to be an added value for the patient and for the improvement of healthcare provided to patients.

Disclosure statements of all authors outside the submitted workProf. Dr. António Morais reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Astra, Novartis, Sanofi and Zanbom.

Prof. Dr. António Bugalho reports personal fees from Astrazeneca, Bial, Fujifilm, Medinfar, Olympus and Pfizer.

Prof. Dr. Marta Drummond reports personal fees from Astra Zeneca, Bial, GSK, Medinfar, Mundipharma, Novartis, Sanofi and Teva.

Prof. Dr. António Jorge Ferreira reports personal fees from Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Mylan, Menarini and TEVA Pharma.

Dr. Ana Sofia Oliveira reports personal fees from Astra, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Medinfar, Menarini, Novartis, Pfizer and Vitalaire.

Dr. Susana Sousa reports personal fees from Bial, GSK, Pfizer, Linde Healthcare Portugal and Phillips Respironics.

Prof. Dr. João Carlos Winck reports personal fees from Armstrong Medical, Breas, Philips, Nippon Gases and Vitalaire.

Prof. Dr. João Cardoso reports personal fees from Astra Zeneca, GSK, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mylan and Novartis.