Seasonal influenza and pneumococcal infection, including community-acquired pneumonia, are preventable diseases that are still causing a significant amount of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1

Influenza epidemics causes each year from 250.000 to 500.000 and Streptococcus pneumoniae nearly 1.5 million deaths worldwide, particularly in frail older patients.2–4

Despite the huge number of recommendations issued by international and national Agency and Scientific Societies, promoting vaccinations in frail and vulnerable patients, vaccine coverage is still unacceptably low.5–9

Even if the number of countries in which influenza vaccination is recommended in high-risk subjects increased by more than 40% between 2014 and 2018, the vaccine uptake did not show any significant increase in the same time-lag.10–11 Notably, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control highlighted that the median vaccination coverage was lower than 50% for elderly and frail individuals, in spite of the goal of vaccinating at least 75% of at risk subjects.12 The recent Sars-CoV2 pandemic reopened the discussion on the strategic arrangements for vaccination in the face of spreading infections, highlighting the vulnerability of older adults with comorbidities to infectious diseases and the need for robust healthcare systems to face the emergency.

Froes F et al., in the present issue of Pulmonology, report interesting results of the Vacinómetro® initiative, an eleven-year study that monitored the influenza vaccine uptake in four different at-risk populations in Portugal.13 The overall figure revealed an increase of vaccination rate in all the four target populations (1.Patients ≥ 65 years old; 2. Patients with chronic conditions; 3. Health care workers (HCWs); 4. Patients 60-64 years old) that reached the coverage target of 75% in the elderly population (group 1).

Free-of-charge vaccination is an important driver for increasing the vaccine uptake and should probably be part of the proactive efforts of any vaccination campaign to provide influenza vaccination to the general population.

The study13 confirms the key role of physicians in promoting vaccinations and in overcoming the most common barriers to vaccination such as fear of adverse effects, uncertainty about the vaccine's efficacy, and misconceptions about the vaccine and the nature of the infection. On the other end it is interesting that HCWs vaccine uptake was as low as 36% in 2011 and reached 59% in 2020.

These results are of paramount importance because it is well known that vaccinating HCWs against influenza is not only a simple and cost-effective measure to reduce infection among staff but also an excellent tool to prevent morbidity and mortality.14

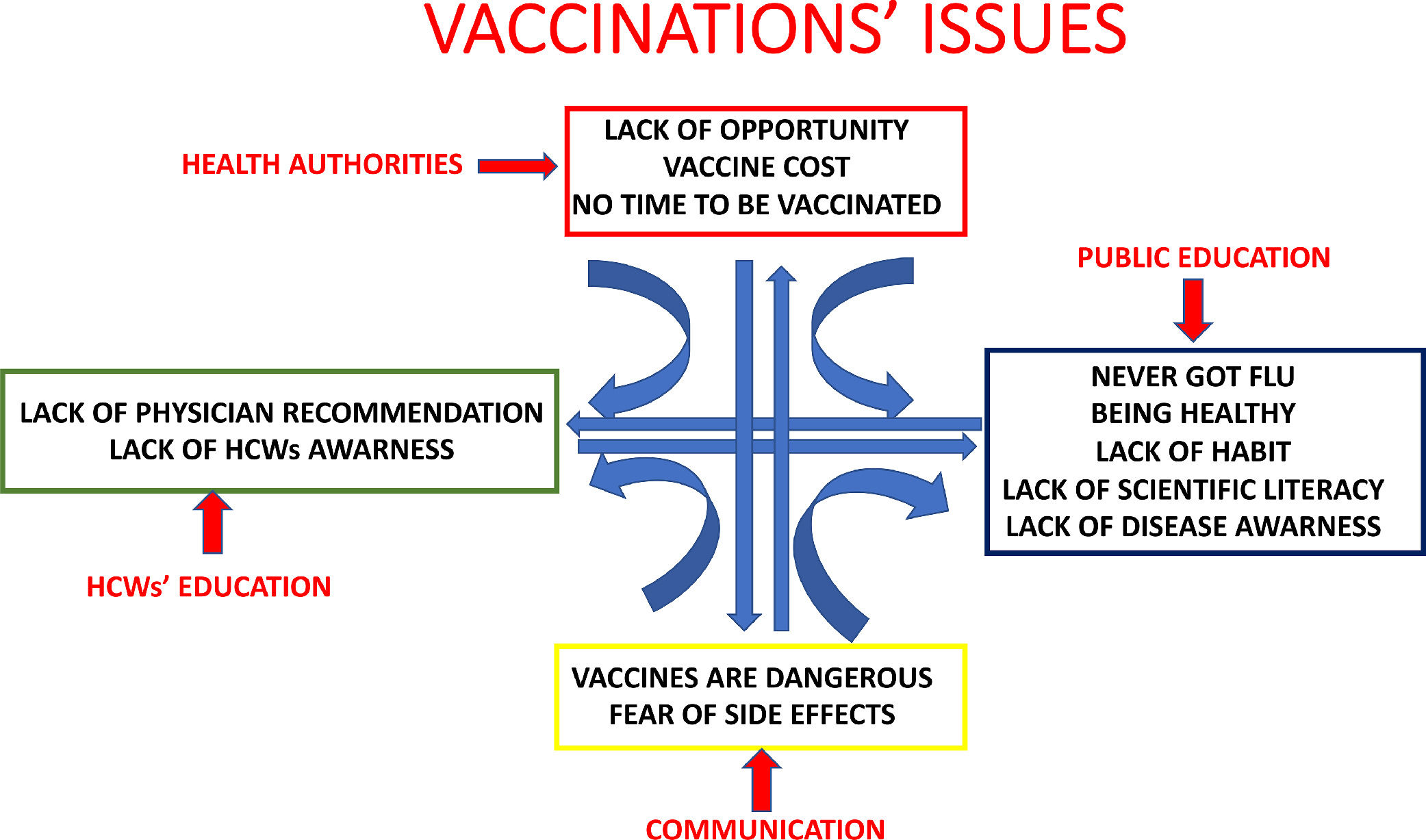

In a survey on attitudes and uptake of H1N1 influenza vaccination among HCWs members of the European Respiratory Society and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases the main reasons for vaccination were to ‘avoid virus spread to patients’ and to ‘protect myself’, and safety being the main concern against vaccination.15 Education of HCWs on vaccination seems to be an important target for improving vaccine uptake both among HCWs and general population. Fig. 1 depicts the major issues concerning vaccinations and the possible proactive interventions.

In conclusion, the article by Froes et al.13 paves the way to a better design of any future vaccination programs, helping health authorities to target the right at risk groups and implementing educational and economical initiatives to improve vaccines uptake.