Current guidelines differ slightly on the recommendations for treatment of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) patients, and although there are some undisputed recommendations, there is still debate regarding the management of COPD. One of the hindrances to deciding which therapeutic approach to choose is late diagnosis or misdiagnosis of COPD. After a proper diagnosis is achieved and severity assessed, the choice between a stepwise or “hit hard” approach has to be made. For GOLD A patients the stepwise approach is recommended, whilst for B, C and D patients this remains debatable. Moreover, in patients for whom inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are recommended, a step-up or “hit hard” approach with triple therapy will depend on the patient's characteristics and, for patients who are being over-treated with ICS, ICS withdrawal should be performed, in order to optimize therapy and reduce excessive medications.

This paper discusses and proposes stepwise, “hit hard”, step-up and ICS withdrawal therapeutic approaches for COPD patients based on their GOLD group. We conclude that all approaches have benefits, and only a careful patient selection will determine which approach is better, and which patients will benefit the most from each approach.

Current guidelines differ slightly on the recommendations for treatment of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) patients, mainly because patient stratification is not consensual across guidelines.1–5 Although there are some undisputed recommendations, such as smoking cessation, physical activity programs, and influenza and pneumococcal vaccination, there is still debate regarding the management of COPD.6–12 The therapeutic approach proposed by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), and based solely on the GOLD classification of COPD,2 is not entirely satisfactory, given the variability within GOLD groups, namely regarding hospitalizations and mortality.13 However, therapy has to be based on some classification system, and the GOLD classification is the most widely accepted, even with its caveats.

One of the hindrances to deciding which therapeutic approach to choose is late diagnosis or misdiagnosis of COPD. Patients who are not diagnosed at the early stages of the disease cannot receive the early treatment which has been shown to be beneficial.6,11,14 On the other hand, patients misdiagnosed with asthma or Asthma-COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS), will be overtreated with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), and are likely to see no improvement in their symptom burden. In fact, two recent analyses showed that, in current clinical practice, ICS are being prescribed inappropriately,15,16 and that thousands of patients may be overtreated.

After a proper diagnosis is achieved, and severity assessed, the choice for a stepwise or “hit hard” approach has to be made, and if for GOLD A patients the stepwise approach is recommended,2 for B, C and D patients this remains debatable.17 The argument for the stepwise approach is to not overtreat patients, but some patients may benefit from a “hit hard” approach, with the aim of maximal bronchodilation.12,13,18–20 In patients who will benefit from dual bronchodilation, a long-acting muscarinic antagonist/long-acting beta-agonist (LAMA/LABA) fixed-dose combination is advantageous.11,12,21–24 Also, in patients for whom ICS is recommended, a step-up or “hit hard” approach with triple therapy will depend on the patient's characteristics.2,4,5,17 For patients who are being overtreated with ICS, ICS withdrawal should be performed, in order to optimize therapy and reduce excessive medications.21,22,25–28 However, this raises another question: how to decide when a patient is being overtreated? There are currently no reliable or accurate biomarkers of response to therapy and disease progression, so the decision concerning ICS withdrawal must be based on the available objective tests and subjective instruments.2

Results from a recent UK Primary Care Setting retrospective study showed that, 24 months after COPD diagnosis and prescription of initial therapy, several treatment strategies are used: switch in medication, stepwise, step-up and ICS withdrawal,28 suggesting that here is an unmet clinical need to refine therapy beyond GOLD and other international and national guidelines.

This paper discusses and proposes stepwise and “hit hard” therapeutic approaches for COPD patients based on their GOLD group. An alternative treatment approach, based on phenotypes, is addressed elsewhere.29 We suggest two subgroups for GOLD A and GOLD B patients, with different therapeutic approaches. Finally, we conclude that, in COPD, therapy should be tailored to the patient, taking into consideration co-morbidities, presence of hyperinflation, history of chronic bronchitis, levels of physical activity, and each individual patient characteristics.

GOLD A patientsIt is difficult to identify asymptomatic GOLD A patients with no exacerbations, given that they have no reason to seek medical help. Spirometric screening of asymptomatic individuals is not supported by evidence, although in individuals over 40 years old and with a smoking history of >10 pack years, spirometry may be performed with the aim of early diagnosis.1 Indeed, some of these patients are identified during screenings, but many of those who are not eligible for screening (e.g., non-smokers), may remain undiagnosed.11 Also, these patients tend to underestimate their symptoms and adapt their daily activities by exercise self-limitation,1 hence reporting to be asymptomatic. These unidentified patients cannot receive the early treatment, which has been shown to be beneficial.6,11,14

Identification of GOLD A patientsBesides screening, these patients are mainly identified in four situations: (a) in clinical visits for other causes or complaints; (b) when they are subjected to tests for non-respiratory reasons; (c) in the emergency room due to an acute episode; or (d) during pre-surgery testing. Once identified, it is imperative not to lose these patients to follow-up, as they will eventually evolve to other GOLD group and therapy will have to be adjusted. A correct diagnosis is of the utmost importance, since it leads to both undertreatment and overtreatment (e.g., COPD diagnosed as asthma).

We suggest an active case-finding approach for the identification of GOLD A patients. We further propose that these patients are flagged whenever they are diagnosed and, thereafter, that they are managed by their general practitioner, in close cooperation with a pulmonologist.

Recommended therapeutic approach for GOLD A patientsGiven that these patients are often excluded from Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs), there are no systematic data available on which therapy should be used or how they will respond.6 Should they be treated? When? With which medication and how? How will they progress with or without therapy? A study based on the ECLIPSE cohort showed that, at 3 years follow-up, 57% of patients initially assigned to GOLD A remained in the A group, whilst the remaining 43% progressed to other GOLD groups.13 Based on this study, all GOLD A patients should receive treatment.

Current guidelines generally recommend for these patients smoking cessation, physical activity programs, and influenza and pneumococcal vaccination. Also, the use of a short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) or a short-acting muscarinic antagonist (SAMA) as needed is mostly consensual, although LABA or LAMA may be used as alternative therapies.1–5 Some authors speculate that early intervention with long-acting bronchodilators may improve patient-reported outcomes.11 However, one major issue with these patients is compliance to long-term drugs,6 and patient education is fundamental in delaying COPD evolution.

In GOLD A patients, both phenotype3,6,30 and co-morbidities1–5 should be taken into account when choosing between a LABA or a LAMA, with the aim of achieving the best outcomes and delaying disease progression. Both LAMAs and LABAs have shown similar profiles regarding FEV1 and dyspnea improvement, exercise tolerance, exacerbations reduction and safety.21,23,24,26,31–40 However, there is some evidence that LAMAs may delay lung function decline34,35 and decrease all-cause mortality,34 and may be more effective than LABAs in preventing exacerbations.41 Despite this, and although LABAs do not seem to influence mortality,42 two studies showed superiority in providing better symptomatic improvement than a LAMA.43,44 These data suggest that LAMAs should be preferred for patients at higher risk of exacerbations, whilst LABAs would be better for symptomatic control, although it depends on the individual clinical response of each patient. If a LABA is chosen, indacaterol may be preferable to other commercially available LABAs since, besides having all the above mentioned advantages of LABAs, it is the only once-daily LABA with studies designed to investigate exacerbations45,46 and proved able to reduce them, although in moderate to severe patients.39,40

However, evidence is still too scarce to propose a recommendation between a LABA and a LAMA. Also, the financial aspect should not be disregarded when choosing between a LABA or a LAMA, as some patients may not be able to afford some therapies and respond well to more affordable alternatives. Dual bronchodilation is not an option for these patients.

Finally, given the heterogeneity of COPD, even patients classified as belonging to the A group show a large variability.

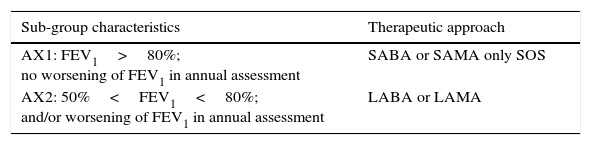

We propose that group A patients need to be sub-divided into two groups, AX1 and AX2, and the therapeutic approach should be based on this subdivision – Table 1.

Proposed division of GOLD A patients in two subgroups and respective therapeutic approaches.

| Sub-group characteristics | Therapeutic approach |

|---|---|

| AX1: FEV1>80%; no worsening of FEV1 in annual assessment | SABA or SAMA only SOS |

| AX2: 50%<FEV1<80%; and/or worsening of FEV1 in annual assessment | LABA or LAMA |

FEV1 – forced expiratory volume in 1 second; SABA – short acting β2-agonist; SAMA – short acting muscarinic antagonist; LABA – long acting β2-agonist; LAMA – long acting muscarinic antagonist.

We further recommend that, if a LABA is chosen, indacaterol may be preferable as it also reduces the rate of exacerbations.

We also recommend that therapy should be tailored to the patient, taking into consideration co-morbidities, presence of hyperinflation, history of chronic bronchitis, levels of physical activity and adverse effects of each drug.

Finally, all COPD patients should be offered a completely free smoking cessation program, including consultations and therapy.

GOLD B patientsCurrent guidelines generally recommend for these patients smoking cessation, physical activity programs, influenza and pneumococcal vaccination, and pulmonary rehabilitation.1–5 All guidelines agree that bronchodilators are the baseline therapy for all stages of COPD, but the choice of which bronchodilator to use is left to the physician.12 Also, most guidelines generally recommend a stepwise approach, and dual bronchodilation only when one bronchodilator is not sufficient to provide satisfactory symptom relief.12 GOLD recommends LAMA or LABA as the first choice medication and LAMA+LABA as the alternative choice.2 If indeed the choice is a stepwise approach, then which long-acting bronchodilator should be used, a LABA or a LAMA? As already discussed above, evidence is still too scarce to propose a recommendation.

On the other hand, Agusti and Fabbri defend the “hit hard” approach with dual bronchodilation for GOLD B patients,17 and there are several arguments in favor of this approach. Group B and C patients show a similar risk of all-cause mortality,13 suggesting that a more aggressive treatment approach should be used in these patients. Also, many patients receiving long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy continue to experience significant symptoms,18 and dual bronchodilation provides better symptomatic relief,12,23,24 improves FEV1 in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD,23,24,47 and improves health status.23 Moreover, reduction of hyperinflation, as achieved with maximal (dual) bronchodilation, increases exercise tolerance,12,31 and higher levels of physical activity are associated with a better functional status48 and reduced risk of hospitalizations and mortality,49 even at levels as low as the equivalent to walking or cycling 2h/week.50 Also, it has been reported that objectively measured physical activity is the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with COPD.51 Therefore, it can be speculated that dual bronchodilation will have both short- and long-term beneficial effects in COPD patients. In patients who will benefit from dual bronchodilation, LAMA/LABA fixed-dose combinations are expected to become the new standard in COPD treatment.9 In GOLD 2 or 3 patients, with or without a history of exacerbations, dual bronchodilation with once-daily indacaterol/glycopyrronium (IND/GLY) has clinically meaningful improvements in symptomatic parameters versus a salmeterol/fluticasone combination (SFC)21,22 and tiotropium,23 and is superior to treatment with its monocomponents, indacaterol and glycopyrronium,23 suggesting the existence of synergistic activity between the LABA and the LAMA.11 IND/GLY also provided superior improvements in patient-reported dyspnea and lung function versus placebo and tiotropium.24 Moreover, indacaterol and glycopyrronium show a very fast and long-lasting (about 24h) relaxation of airway smooth muscle.12 There are several potential advantages and beneficial effects of having a combination of LABA+LAMA on the same device.52

Finally, given the heterogeneity of COPD, even patients classified as belonging to the B group show large variability.

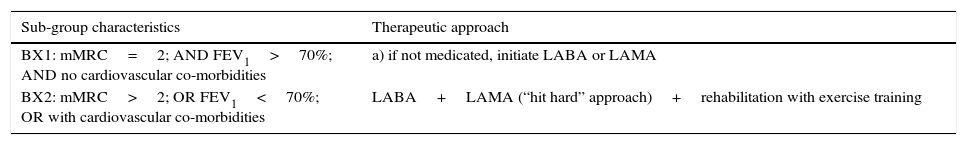

We propose that group B patients need to be sub-divided into two groups, BX1 and BX2, and the therapeutic approach should be based on this subdivision – Table 2.

Proposed division of GOLD B patients in two subgroups and respective therapeutic approaches.

| Sub-group characteristics | Therapeutic approach |

|---|---|

| BX1: mMRC=2; AND FEV1>70%; AND no cardiovascular co-morbidities | a) if not medicated, initiate LABA or LAMA |

| BX2: mMRC>2; OR FEV1<70%; OR with cardiovascular co-morbidities | LABA+LAMA (“hit hard” approach)+rehabilitation with exercise training |

mMRC – modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale; FEV1 – forced expiratory volume in 1 second; LABA – long acting β2-agonist; LAMA – long-acting muscarinic antagonist.

We further recommend that, when the treatment of choice is dual bronchodilation, a combination of LABA+LAMA on the same device is preferable.

GOLD C and D patientsIn addition to all general recommendations for GOLD B patients,1–5 guidelines suggest: LAMA and/or LABA, with or without ICS,1,2,4 with ICS recommended for patients with frequent exacerbations that are not adequately controlled by long-acting bronchodilators;2,4 a stepwise or step-up approach, or immediate triple therapy, depending on frequency of exacerbations;5 no recommendation for ICS on the non-exacerbator patient phenotype.3 Agusti & Fabbri propose a stepwise or step-up approach depending on dyspnea and risk of exacerbations, respectively.17 A recent analysis showed that, in current clinical practice, however, group D patients are more frequently prescribed triple therapy, regardless of pulmonary function and risk of exacerbations,16 which is contrary to what the guidelines recommend.

Regarding dual bronchodilation, several randomized clinical trials in GOLD 2 to 4 patients, with or without a history of exacerbations, showed that dual bronchodilation with IND/GLY improves symptoms,21–24,37 and prevents moderate to severe COPD exacerbations.37 In the SHINE,23 BLAZE24 and SPARK37 studies, patients already on ICS therapy at baseline maintained the ICS during the study, whereas in the ILLUMINATE21 and LANTERN22 studies patients on ICS therapy before study start underwent a washout period. Taken together, these data suggest that dual bronchodilation is an appropriate treatment option for patients with severe and very severe COPD.

C and D subgroupsTherapeutic options have to consider the three C and D subgroups:

- -

C1, D1 (high risk due to poor function)

- -

C2, D2 (high risk due to exacerbations)

- -

C3, D3 (high risk due to both poor function and exacerbations)

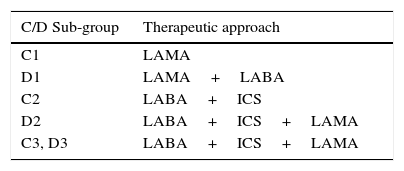

We propose that the therapeutic approach is based on these subgroups – Table 3. When the treatment of choice is dual bronchodilation, a combination of LABA+LAMA on the same device is preferable. For C1 and D1 patients, a stepwise or “hit hard” approach should be decided depending on symptoms, with the “hit hard” approach recommended in strongly symptomatic patients. For C2, D2, C3 and D3 patients, a step-up approach or immediate triple therapy should be decided depending on the frequency of exacerbations. We suggest the patient to be re-assessed every 3 months during a one year period after initiation of ICS (spirometry, the Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale (mMRC), the COPD Assessment Test (CAT), inflammation, symptoms). We further recommend that, if there were no exacerbations during 12 months, COPD was stable, and assessed parameters are within the expected range, withdrawal of ICS could be considered.

Proposed therapeutic approach for C and D patients.

| C/D Sub-group | Therapeutic approach |

|---|---|

| C1 | LAMA |

| D1 | LAMA+LABA |

| C2 | LABA+ICS |

| D2 | LABA+ICS+LAMA |

| C3, D3 | LABA+ICS+LAMA |

C1, D1 – patients at high risk due to poor function; C2, D2 – patients at high risk due to exacerbations; C3, D3 – patients at high risk due to both poor function and exacerbations; LABA – long acting β2-agonist; LAMA – long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS - inhaled corticosteroid.

Although ICS are not indicated for patients without exacerbations,2–5,17 ICS/LABA or even triple therapy is widely prescribed in real-life management of COPD, even in patients with mild or moderate COPD severity. Both General Practitioners and specialists in respiratory medicine often use triple therapy even for patients who are not suffering from severe COPD.8 Although the reasons for this are unclear, we speculate that this is mainly due to the generalized idea that a patient taking ICS will be more controlled than a patient who is not on ICS therapy, and will not exacerbate or decompensate. This is not true. In fact, patients who do not need ICS therapy will be overmedicated, will not benefit from triple therapy, and will suffer all the possible adverse events of ICS, namely pneumonia.

A recent review from UK general practice showed that, in 2009, patients in all GOLD stages were receiving triple therapy.15 The question of whether the less severe patients were frequent exacerbators, and thus being treated according to the current guidelines, remained unanswered. Another recent analysis confirmed that, in current clinical practice, ICS are indeed used inappropriately.16 These reports indicate that ICS prescription does not follow the current guidelines and thousands of patients may be overtreated.

Withdrawal from ICSIf patients are indeed being overtreated, then they will not only be subjected to the ICS’ numerous side effects but they will also not benefit from the ICS, rendering the risk/benefit ratio of the ICS too high to justify its use. A systematic review from 2011 on trials with withdrawal of ICS found no evidence that withdrawing patients from ICS in routine practice led to important deterioration of outcomes, namely frequency of exacerbations and exercise tolerance. Only one of the included trials reported a significant decline in lung function.53 The ILLUMINATE21 and the LANTERN22 studies showed that, in GOLD 2 and 3 patients with or without one moderate or severe exacerbation in the previous year, ICS can be safely withdrawn, and once-daily IND/GLY provided significant, sustained, and clinically meaningful improvements in lung function versus twice-daily SFC. In addition, IND/GLY provided significant symptomatic benefit and was superior to SFC in achieving bronchodilation and reducing the rate of exacerbations. Another study in which ICS therapy was either switched or withdrawn, in patients with moderate to severe COPD, showed that ICS can be safely discontinued, and the addition of fluticasone–salmeterol to tiotropium may improve lung function and decrease hospitalizations, but does not affect rates of exacerbations.26 The OPTIMO study,27 a real-life study, showed that ICS may be withdrawn, provided appropriate therapy with bronchodilators is maintained, but the WISDOM study54 showed that ICS withdrawal had no effect on exacerbations but led to a decrease in pulmonary function. The different results from the OPTIMO and WISDOM studies may lie in one simple fact: in the OPTIMO27 study patients had an average FEV1≈71% predicted, being probably non-exacerbator GOLD B patients, and therefore did not need ICS, whilst the WISDOM54 study patients had much more severe airway limitation (FEV1≈34% predicted, GOLD 3 and 4), probably fitting the criteria for ICS use, and were thus affected by withdrawal. Another explanation for these results lies in the design of the WISDOM study, where even patients who had never been on ICS, received an ICS-containing triple therapy for 6 weeks before randomization. Moreover, the OPTIMO study explicitly excludes patients with a “history of asthma”, whilst the WISDOM study excludes patients with a “current diagnosis of asthma”, which makes it possible for patients with ACOS to be included in the WISDOM study.

A very recent UK Primary Care Setting retrospective study shows that, in newly diagnosed COPD patients, withdrawal from ICS is common after 12 or 24 months of therapy initiation.28 Unfortunately, and although included patients were classified as GOLD 1 to 4, treatment approaches used were not stratified by GOLD stage.

Regardless all available evidence, there is a generalized concern among physicians that, if a patient is withdrawn from ICS, that patient will decompensate or exacerbate. Even if the patient is re-assessed and does not have indications for ICS, the reluctance to withdraw remains. This concern stems mainly from the results of the TORCH19,20,42 trial, which convinced the community of physicians that ICS improves several outcomes, slows disease progression and reduces moderate-to-severe exacerbations, even if failing to show a beneficial effect of ICS on all-cause mortality rates. However, in light of more recent data, as presented above, there is no evidence-based reason for such a concern.

Another hindrance to deciding whether to withdraw from ICS or not is misdiagnosis, e.g. COPD misdiagnosed as asthma, or suspicion of the ACOS phenotype. The only way to overcome this hindrance is to attain a proper diagnosis.

Finally, patients prefer to be withdrawn from ICS due to the general perception that corticosteroids are “dangerous” – and indeed they can be, if not properly prescribed.

We recommend that A and B patients without exacerbations, who are overtreated with ICS, should be withdrawn from ICS in order to optimize therapy and reduce excessive medications, provided they are not ACOS, and kept on close surveillance. C and D patients without exacerbations should also be withdrawn from ICS, with re-assessments recommended every 3 months during a one year period.

How to withdraw from ICS?The two options are withdrawal of ICS with or without tapering off. The UK Primary Care Setting retrospective study does not specify how withdrawal from ICS was achieved.28 Both the ILLUMINATE study21 and the LANTERN study22 mention a washout period of up to 7 days, but also do not specify if this period was with or without tapering off. Aaron et al. also do not specify how ICS was discontinued.26 The OPTIMO study27 does not mention how ICS was withdrawn, but the WISDOM study54 does specify that ICS was tapered off over a 12 week period.

Given the lack of concrete data, we can only speculate that if a patient does not need ICS, then there is no need to taper off. In addition, as it is a non-systemic medication, there is no scientific rationale for tapering off.

We recommend that patients with no exacerbations during 12 months and who are stable should be withdrawn from ICS. Tapering off is not necessary and ICS should be withdrawn in a single step. We suggest GOLD A and B patients be re-assessed every 6 months, and Gold C and D patients every 3 months, during a one year period after ICS withdrawal (spirometry, mMRC, inflammation, symptoms). We further recommend that, in C and D patients, if there were exacerbations during 6 months, or if pulmonary function consistently decreases, there should be a step-up with ICS.

Which patients will benefit from ICS?There is a need for biomarkers of response to therapy and disease progression, so that the moment of therapeutic adjustments can be determined in a timely way. Some biomarkers of disease activity and progression have been proposed,55,56 but much more research needs to be done before these are clinically applicable, and can guide personalized management of COPD patients. Perhaps the most promising available marker is sputum eosinophilia, and most recently also blood eosinophilia.57 COPD patients with sputum eosinophilia>3% seem to respond better to both ICS and systemic corticosteroids.10,58–61 As for circulating levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), results from different studies are controversial, and CRP may not be a suitable biomarker in COPD, due to its low specificity and high variability.58

We recognize that there are currently no accurate biomarkers to guide therapy in COPD. We propose that CAT should be used in all consultations, in order to monitor therapeutic response, given it is a predictor of exacerbations.

ICS class, dose and pneumoniaThe consensus is that ICS use increases the risk of pneumonia in patients with COPD,1,2,4,20–22,36,62 and even a recent ICS, fluticasone furoate, has been associated with an increased pneumonia risk and deaths from pneumonia in COPD patients.62–64 However, some studies find a very small difference in the risk of pneumonia with ICS.21,22,26 These dissimilar results may stem from the fact that some studies are too short for patients to develop pneumonia, and/or that several ICS classes and doses are used in different studies. Both fluticasone and budesonide have been reported to increase the risk of pneumonia,64–67 but results concerning a dose effect range from no difference between fluticasone and budesonide,65 to fluticasone being associated with a higher, dose dependent risk, when compared to budesonide,66 to fluticasone not being dose dependent, while budesonide shows a significant difference between the two commonly used doses.67 The general dose-effect of ICS on pneumonia risk has been confirmed in a large USA retrospective cohort study, but the use of several ICS classes precludes any conclusion regarding specific ICS class-related dose-effect.68

Results concerning the true effect of different ICS classes and doses on the risk of pneumonia remain inconclusive. More studies are needed to allow an evaluation of whether different classes of ICS are associated with different pneumonia risk in COPD patients.

Given the controversy surrounding ICS therapy in COPD patients, we suggest that a withdrawal or step-up approach should take into account the above recommendations but be tailored to the patient, taking into consideration each individual patient characteristics.

ConclusionsBoth stepwise and “hit hard” approaches have benefits. Only a careful patient selection will determine which approach is better, and which patients will benefit the most from each approach. In COPD, therapy should be tailored to the patient, taking into consideration co-morbidities, presence of hyperinflation, history of chronic bronchitis, levels of physical activity, and each individual patient characteristics.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare collaborating and receiving fees from pharmaceutical companies other than Novartis either through participation in advisory board or consultancy meetings, congress symposia, clinical trial conduct or investigator-initiated trials.

Role of funding sourceFunding for this paper was provided by Novartis Portugal. Funding was used to access all necessary scientific bibliography and cover meeting expenses. Novartis Portugal had no role in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the paper and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

The authors wish to thank Novartis Portugal for the funding for this paper, which was used to access all necessary scientific bibliography and cover meeting expenses.