Systemic steroids in patients with asthma can induce various complications such as infection, diabetes, and osteoporosis, and increase healthcare resource utilization. Biologics are a corticosteroid-sparing strategy,1 and recently, “super-responders” i.e., patients who show excellent response to biologics, which results in complete cessation of exacerbations and permits discontinuation of systemic steroids, have gained attention.2 This report describes a patient with severe asthma who became a super-responder to cycling biologic therapy using 2 biologics with mepolizumab and dupilumab.

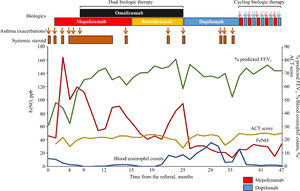

We describe the case of a 47-year-old man who had childhood asthma. The patient had a relevant history of smoke exposure (44 pack-years) and experienced respiratory symptoms for the first time in adult age (42 years old). Nasal polyp removal surgery was performed at the age of 45 years. Although he was treated with fluticasone furoate 200 μg/vilanterol 25 μg once daily and montelukast 10 mg once daily, he continued to have recurrent asthma exacerbations, requiring the use of systemic corticosteroids. He was then referred to the Department of Airway Medicine of Mitsubishi Kyoto Hospital. He was aspirin tolerant. His body mass index was 33.0 kg/m2. He suffered from paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea and exacerbations of respiratory symptoms at night and in the morning. Chest radiography did not reveal lung hyperinflation. His blood eosinophil counts were 5.9% (535.7/μl), and fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) level was 46 ppb. His total immunoglobulin E (IgE) level was 127 IU/mL, and the IgE expression specific for Japanese cedar was detected. Sinus computed tomography findings showed that total Lund-Mackay score (LMS) was 14 points with predominant opacification of the ethmoid sinuses. His % predicted forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and FEV1/forced vital capacity were 31.3% (normal value: 3.58 L) and 46.1%, respectively. We ruled out asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap, because his clinical symptoms were characterized by diurnal variability, the presence of a high LMS,3 and the absence of lung hyperinflation. Fig. 1 shows the clinical course of the patient. We modified the inhaled corticosteroid therapy to four puffs of budesonide 160 μg/formoterol 4.5 μg twice daily with a technique of nasally exhaling after inhaling at “fast” inspiratory flow4 and added tiotropium Respimat® (5 μg once daily). At 2 months after the referral, mepolizumab was started at a dose of 100 mg once monthly. However, the asthma attacks continued, requiring the use of systemic corticosteroids. Thus, administration of oral methylprednisolone 4 mg every other day was started. The asthma attacks still continued, requiring the use of additional systemic corticosteroids. At 8.5 months after the referral, omalizumab was additionally administered at a dose of 600 mg once monthly. At 3 months after the initiation of dual biologic therapy with mepolizumab and omalizumab, the oral methylprednisolone therapy was discontinued. However, the patient complained of asthma symptoms such as wheezing and coughing which were waking him up at night at a frequency of more than once a week. This required the use of systemic steroids even though total asthma control test (ACT) scores were higher than 20. This prompted a shift of medication from mepolizumab to benralizumab 30 mg every 8 weeks after three initial doses given every 4 weeks. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for dual biologic therapy with omalizumab and mepolizumab or benralizumab and for publication of this case report. After the initiation of dual biologic therapy with omalizumab and benralizumab, no asthma exacerbations were observed. However, 8 months after the initiation of the dual biologic therapy with omalizumab and benralizumab, the blood eosinophil count increased from 0.2% to 8.4% and continued to increase. The patient experienced two asthma attacks, requiring the use of systemic corticosteroids. We shifted from dual biologic therapy with omalizumab and benralizumab to dupilumab 300 mg (initial dose of 600 mg) every 2 weeks. Thereafter, the blood eosinophil counts tended to decrease. However, 6 months after the initiation of dupilumab, the blood eosinophil counts increased again, and three asthma attacks occurred, requiring the use of systemic corticosteroid. No sensory disturbance and motor weakness were observed. Chest radiography revealed no remarkable abnormalities. At 10.5 months after the initiation of dupilumab therapy, cycling biologic therapy comprising a cycle of dupilumab administered twice every 2 weeks in a month after a single administration of mepolizumab was initiated. Total LMS was 0 point at 5 months after the initiation of cycling biological therapy. During the 12-month follow-up period, the patient did not use a short-acting beta agonist or systemic steroids, did not require emergency department visits or hospital admissions, and showed no decrease in ACT scores or elevation in eosinophil count. Additionally, no adverse effects occurred.

Status of asthma exacerbations and the use of systemic steroids and changes in blood eosinophil counts, % predicted FEV1, ACT score, and FeNO level after the referral. †Asthma exacerbation was defined as acute events requiring systemic steroids. ACT, asthma control test; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide.

As proposed by Zervas E, et al., although omalizumab and dupilumab can be prescribed to patients with predominantly allergic asthma, mepolizumab, benralizumab, reslizumab, and dupilumab may be more suitable in those with eosinophilic asthma.5 Thus, in asthmatic patients with both allergic and eosinophilic features in whom single biologic therapy cannot control symptoms, dual6 or cycling7 biologic therapy, using a combination of omalizumab or dupilumab with mepolizumab, benralizumab, reslizumab, or dupilumab can be prescribed to concomitantly control both features. Our patient presented with eosinophilic features such as elevated eosinophil counts (>300/μl), FeNO (>50 ppb), and chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, along with allergic features such as early onset, high total IgE levels (>100 IU/mL), and also tested positive for Japanese cedar-specific IgE, implying that his asthma had both allergic and eosinophilic features. Thus, dual and cycling biologic therapy, in addition to single biologic therapy, rendered the patient a “super-responder” to cycling therapy with dupilumab and mepolizumab as he did not experience loss of asthma control or any exacerbations that required systemic steroids, emergency department visits, or hospital admissions.8

The cost associated with cycling biologic therapy is similar to that of single biologic therapy, whereas dual biologic therapy is very expensive. On the other hand, in cycling biologic therapy, it is not known if the effects of the biologic persist even when it is not administered. Additionally, effects of the interaction of biologics are unknown in dual or cycling biologic therapy. Therefore, large randomized studies are needed to confirm the efficacy and safety of dual and cycling biologic therapy in managing severe asthma in patients who are unresponsive to single biologic therapy and to identify subgroups that are likely to benefit from these biologic therapies.

AuthorshipSH, EO, and HY wrote the manuscript. SH and HY followed the patient. SH, EO, and HY read and approved the final manuscript.