Besides the well-known relationship between connective tissue diseases (CTDs) and several forms of interstitial lung disease (ILD), the recognition of autoimmune features in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias led to the establishment of the IPAF (interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features) denomination and classification criteria in 2015.1

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) and several CTDs share T cell dysregulation, suggesting a greater likelihood of autoimmune disease in HP patients. A previous study of a cohort of chronic, fibrotic HP patients found that fifteen percent of these patients revealed either the presence of a defined CTD or some autoimmune features suggestive of CTD. These patients were identified as having “HP with autoimmune features” (HPAF) and seemed to have a worse survival rate than non-HPAF HP patients.2

We report a case of a 72-year old man who is followed as a Pulmonology outpatient due to obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, under home continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with mild centrilobular emphysema and mediastinal lymph node enlargement. Inhalation exposure is relevant due to former smoking habits (thirty pack-years), close contact with birds in the backyard, occasional use of sauna and Turkish Baths. As for past medical history, the patient also has arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, unknown chronic liver disease and a previous rheumatological diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis, currently without directed therapy; a previous hospital admission happened due to community-acquired pneumonia. Chronic medications are an association of two anti-hypertensive drugs and atorvastatin.

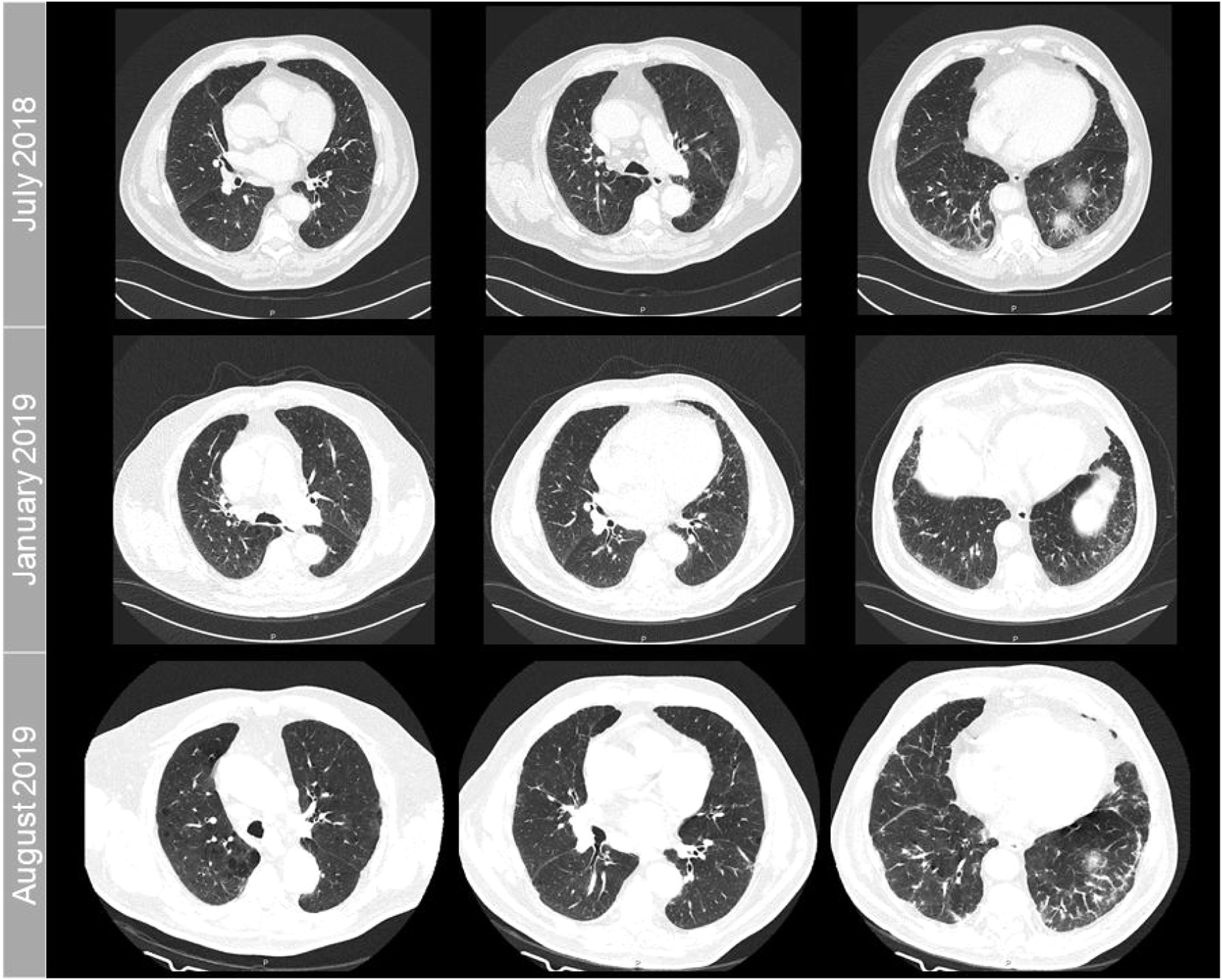

Follow-up chest high-resolution CT scans showed progressive, unspecific, peripheral lower lung lobes intralobular reticulation (Fig. 1), as well as lymph node enlargement (14mm) in the left paratracheal station (4L). Endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) was performed; the 4L station was identified and sampled and its cytological analysis was unremarkable.

Follow-up chest CT scan axial images showing progressive, unspecific peripheral intralobular reticulation in the lower lung lobes. The time when the scans were performed is indicated on the left of each row of images. For comparative purposes, the images in each column correspond to identical axial planes.

Meanwhile, the patient reported worsening exertional dyspnea. Body plethysmography identified a mild obstructive ventilatory defect: FEV1/VC ratio equal to 64.2% and FEV1 equal to 2.41L (86% of the predicted value). There was no lung diffusion impairment. Fibreoptic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in the middle lobe was performed. BAL fluid cellular analysis showed a normal total cell count, an intense lymphocytic alveolitis (55.6%) and a CD4/CD8 ratio of 1.87; bronchial wash and BAL were negative for malignant cells or microbiological agents. Serum immunological study was positive for anti-nuclear antibodies (1/1000 titer, speckled pattern).

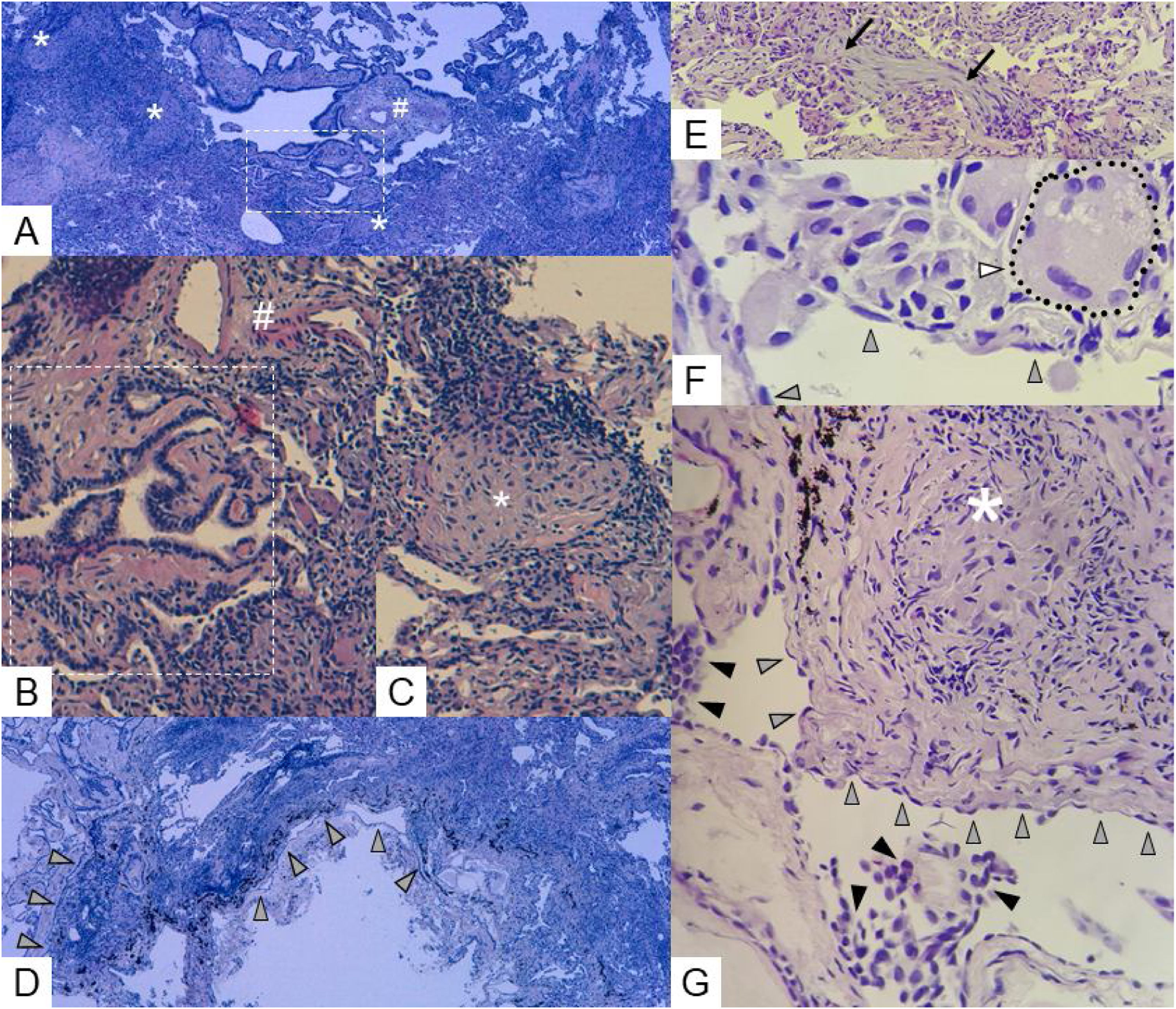

The decision to perform transbronchial lung cryobiopsy (TBLC) was made in ILD interdisciplinary meeting for diagnostic clarification. Histological analysis of three samples from the right lower lobe showed features suggestive of both HP and autoimmunity (Fig. 2).

TBLC histopathology findings in HPAF. There are expressive peribronchiolar and subpleural changes, typical of HP and CTDs, respectively.

(A) A prominent, dense interstitial chronic inflammatory infiltrate without lymphoid follicles with a predominantly bronchiolocentric distribution is seen. There are extensive lesions of peribronchiolar metaplasia (white - - - - -) and loose aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes – epithelioid granulomas (white *). A centrilobular region is marked with white # – hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, 40× magnification.

(B) Detail of a lesion of peribronchiolar metaplasia (white - - - - -), adjacent to the centrilobular region (white #) – H&E staining, 200× magnification.

(C) Detail of an epithelioid granuloma (white *) – H&E staining, 200× magnification.

(D) A moderate cellular chronic inflammatory infiltrate, extensively involving subpleural areas (

), as well as alveolar septa, is also seen – H&E staining, 40× magnification.(E) Detail of organizing pneumonia lesion (→) – H&E staining, 200× magnification.

(F) Detail of a multinucleated giant cell (▷ and •••••••) adjacent to the visceral pleura (

) – H&E staining, 400× magnification.(G) Detail of a pleura-centered epithelioid granuloma (white *) and focal mesothelial reactivity (►) interspersed with normal pleural mesothelium (

) – H&E staining, 200× magnification.A working diagnosis of HPAF was established in an ILD multidisciplinary meeting.

This case report shows the diagnostic challenges of HPAF. It is still unclear whether autoimmune features in HP are a distinct HP clinical phenotype or an unrelated finding. However, we think that both HPAF and non-HPAF HP patients deserve further study in future prospective studies, specifically regarding immunosuppressive therapy outcomes.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

We would like to thank all the remaining elements of the ILD interdisciplinary meeting for the decisive contributions to the diagnosis of the patient: André Carvalho, MD (Radiology), Conceição Souto Moura, MD (Anatomic Pathology), Hélder Novais e Bastos, MD, PhD (Pulmonology), José Miguel Pereira, MD (Radiology), Patrícia Mota, MD (Pulmonology) and Rui Cunha, MD (Radiology).