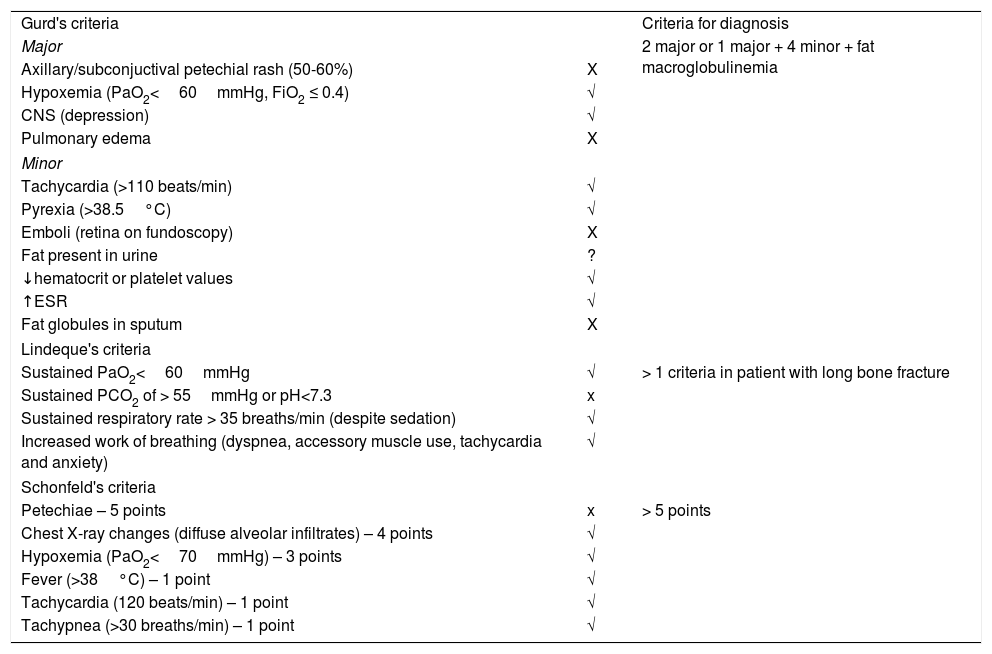

Fat embolism is a rare, life threatening clinical entity caused by a temporary or incomplete blockage of blood vessels by fat globules. Its association with long bones fractures is well known (80% of the cases), although it can have an atraumatic cause. The diagnosis is made on clinical grounds so a high level of suspicion is usually crucial. The use of clinical criteria (Gurd's, Lindeque's or Schonfeld's criteria) helps the diagnosis of fat embolism, although none of them have been validated yet.1-4

Symptoms typically emerge after 24-72hours of the initial injury; the pulmonary system is the one most commonly involved (95%), followed by the central nervous system and skin. Patients usually manifest severe hypoxemia and respiratory distress. Petechial rash in the conjunctiva, oral mucosa and skin folds can occur in 60% of the cases.4

Laboratory tests can show anemia, thrombocytopenia, prothrombin time prolongation, hypocalcaemia, raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), elevated serum lipase and hypofibrinogenemia.4,5

We present a case of a 26-year-old man, previously healthy and non-smoker, admitted to the hospital with right lower leg long bone fracture (tibia and fibula) after a bicycle accident. He was submitted to surgery after a couple hours with general anesthesia. Hypoxemia was initially reported during surgery. In the next 48h he developed taquypnea, sleepiness, fever and profound hypoxemia while on the Orthopedic ward. On physical examination he was oriented but sleepy, tachycardic, with severe hypoxemia (SpO2 readings of 80%) although this was surprisingly well tolerated, lung sounds with basal crackles and normal arterial blood pressure. He had no cervical or axillary rash.

Arterial blood gas analysis showed a type I respiratory failure with a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 160 and normolactacidaemia. Chest X-ray revealed diffuse alveolar infiltrates. Laboratory tests showed an hemoglobin level drop of 1.8g/dL (13.2->11.4g/dL) (range 13.0-18.0g/dL), raised ESR (100mm/h, range < 15mm) and C-reactive protein (18.6mg/dL, range < 0.5,g/dL). The coagulation study was normal.

Considering the fact that his breathing was, surprisingly, almost normal, a group decision was taken to post-pone ICU admission. He was transferred to the Pulmonology ward and stabilized on high flow oxygen under careful surveillance.

High-resolution chest-CT (HRCT) followed by CT angiogram were performed which helped to exclude pulmonary venous embolism and revealed extensive bilateral parenchymatous abnormalities with areas of “crazy-paving” pattern along with patchy ground-glass infiltrates with dependent distribution (Fig. 1).

Blood cultures and urinary antigen testing were microbiologically negative. The patient underwent flexible bronchoscopy with the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) showing aliquots which had become progressively more hemorrhagic, confirming diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH). BAL complete microbiological workup was negative.

Autoimmune sorological study was unremarkable and HIV status was negative.

The patient underwent a dilated fundoscopy, although only after a delay of 5 days, and “cotton wool spots” or Purtscher's retinopathy was excluded.

After excluding other causes, given the age of the patient and in the context of a clear precipitating factor, the suspicion for fat embolism was supported on clinical grounds. (Table 1) The diagnosis of the DAH fitted in with the previous suspicion as, although rare, a pattern of “fat emboli-associated DAH” has already been previously reported in the literature as a possible lung injury pattern related to embolic phenomena. This is at present only the 11th worldwide case reported of DAH secondary to fat embolism.4,6,8-10

Diagnostic Criteria for Fat Embolism.

| Gurd's criteria | Criteria for diagnosis | |

| Major | 2 major or 1 major + 4 minor + fat macroglobulinemia | |

| Axillary/subconjuctival petechial rash (50-60%) | X | |

| Hypoxemia (PaO2<60mmHg, FiO2 ≤ 0.4) | √ | |

| CNS (depression) | √ | |

| Pulmonary edema | X | |

| Minor | ||

| Tachycardia (>110 beats/min) | √ | |

| Pyrexia (>38.5°C) | √ | |

| Emboli (retina on fundoscopy) | X | |

| Fat present in urine | ? | |

| ↓hematocrit or platelet values | √ | |

| ↑ESR | √ | |

| Fat globules in sputum | X | |

| Lindeque's criteria | ||

| Sustained PaO2<60mmHg | √ | > 1 criteria in patient with long bone fracture |

| Sustained PCO2 of > 55mmHg or pH<7.3 | x | |

| Sustained respiratory rate > 35 breaths/min (despite sedation) | √ | |

| Increased work of breathing (dyspnea, accessory muscle use, tachycardia and anxiety) | √ | |

| Schonfeld's criteria | ||

| Petechiae – 5 points | x | > 5 points |

| Chest X-ray changes (diffuse alveolar infiltrates) – 4 points | √ | |

| Hypoxemia (PaO2<70mmHg) – 3 points | √ | |

| Fever (>38°C) – 1 point | √ | |

| Tachycardia (120 beats/min) – 1 point | √ | |

| Tachypnea (>30 breaths/min) – 1 point | √ | |

Along with high flow oxygen support by a Hudson non-rebreathing mask, the patient was put on iv methylprednisolone (1mg/kg 12/12h) for 8 days and responded favourably. Fever subsided after 3 days, along with progressive clearing of the radiographic abnormalities and normalization of oxygenation, respiratory and heart rate and hemoglobin level. The patient was eventually discharged home on a 4 week regressive course of prednisolone and at 2 month reevaluation he was found completely asymptomatic, with normal lung function tests and a normal HRCT.

Fat embolism can account for multiple clinical presentations. DAH is a very rare manifestation of fat embolism. One of the suggested mechanisms relies on an inflammatory response to lipoprotein lipase (LPL) which is activated by circulating catecholamines produced in situations of stress. LPL then acts on the capillary fat liberating free fat acids that induce intravascular coagulation, lipid peroxidation and chemokine-derived inflammatory cell infiltration ultimately leading to alveolar-capillary membrane damage and cell injury.4,7

DAH is usually suspected on the basis of bilateral diffuse alveolar opacities, hemoglobin fall, with or without hemoptysis and evidence of a progressive hemorrhagic BAL. Fat embolism could also justify presence of lipid-laden macrophages on BAL.8

There are no reliable studies addressing therapeutic management other than supportive treatment for fat embolism. However, for fat embolism-associated DAH, anti-inflammatory drugs like corticosteroids have been suggested as useful.4 Prognosis is typically considered good.4,6

FinancingNone to declare

Conflict of interestsNone to declare

None to declare