Interstitial lung diseases (ILD) are a heterogeneous group of disorders.1 Although the disease remains stable in some patients, episodes of acute respiratory failure (ARF) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) are observed.2 Acute respiratory failure is often the result of disease progression or an acute exacerbation, but occasionally occurs as an inaugural manifestation or as an adverse reaction to treatment.1,3

We conducted a retrospective cohort study including patients admitted into ICU, with previously known ILD diagnosis and as an inaugural event, between January 2004 and May 2015, in order to evaluate the clinical outcome, overall survival and prognostic factors of ILD patients in the ICU setting.

Thirty seven patients were included, 27 (73%) were male. Mean age of 65.1±11.1 years (min: 27; max: 83).

Thirty (81.1%) patients were admitted with previous ILD diagnosis. The diagnoses of the patients admitted in ICU were: 5 (13.5%) idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF); 5 (13.5%) silicosis; 5 (13.5%) fibrotic unclassifiable ILD; 5 (13.5%) small vessel vasculitis (ANCA +); 4 (10.8%) chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis; 3 (8.2%) sarcoidosis; 2 (5.5%) rheumatoid lung (RL); 2 (5.5%) acute interstitial pneumonitis; 2 (5.5%) unclear ILD; 2 (5.5%) cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP); 1 (2.7%) scleroderma lung and 1 (2.7%) dermatomyositis.

Seventeen had received previous therapy with corticosteroids, 8 immunosuppressant therapy and 10 long term oxygen therapy.

The median length of ICU and hospital stay were 10 days (min: 1; max: 64) and 21 days (min:1; max:100) respectively. Mean APACHE II score was 18.3±7 and mean SAPS II was 36.9±11.5.

Four lung biopsies were performed: 1 surgical lung biopsy and 3 core needle biopsies guided by CT scan. Two of the biopsies were consistent with acute interstitial pneumonitis, 1 with COP and 1 was unclear.

Seventeen (45.9%) patients had acute exacerbation and twenty experienced ARF due to rapid deterioration of disease associated with respiratory infection.

Thirty three patients (89.2%) required IMV, with an median duration of 10 days (min: 1; max: 62). Nine (24.3%) underwent non-invasive ventilation prior to IMV, 6 required tracheostomy and 3 extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Thirty two patients (86.5%) were treated with antibiotics, 21 (56.8%) with corticosteroids, 8 (21.6%) with antifungals, 6 (16.2%) with cyclophosphamid, 6 (16.2%) with antivirals, 2 (5.4%) with plasmapheresis and 1 (2.7%) with rituximab.

Fourteen (37.8%) patients were discharged from the ICU: 4 small vessel vasculitis (ANCA+); 3 silicosis; 2 sarcoidosis; 2 COP; 1 fibrotic unclassifiable ILD; 1 RL and 1 scleroderma lung.

Twenty three 23 patients (62.2%) died in ICU: IPF (5); chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis (4); fibrotic unclassifiable ILD (4); silicosis (2); acute interstitial pneumonitis (2); unclear ILD (2); sarcoidosis (1); small vessel vasculitis (ANCA +) (1); RL (1); dermatomyositis (1). Short term mortality (first month) and overall hospital mortality were 50% (7 patients) and 86.5% (32 patients) respectively.

Four patients did not require IMV: 1 had COP, 1 unclassifiable ILD, 1 small vessel vasculitis (ANCA+) and 1 RL. From this set of patients only the one with small vessel vasculitis (ANCA+) remains alive, the others died in hospital after ICU discharge.

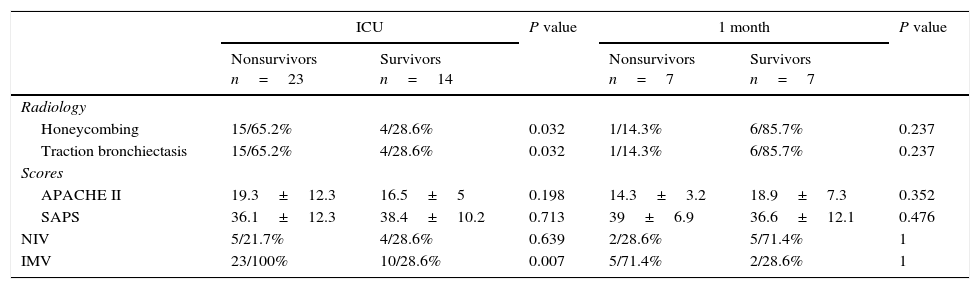

A fibrotic ILD with traction bronchiectasis and honeycombing was associated with a worse outcome (p=0.031 and p=0.031), as well as the need of IMV (p=0.007). A worse outcome was not associated with a higher APACHE II score (p=0.198), a higher SAPS II score (p=0.713), previous oxygen therapy (p=0.353) or previous immunosuppressant therapy (0.982). None of the other parameters analyzed were associated with a worse outcome probably due to the small sample size (Table 1).

ICU and short term outcomes.

| ICU | P value | 1 month | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsurvivors n=23 | Survivors n=14 | Nonsurvivors n=7 | Survivors n=7 | |||

| Radiology | ||||||

| Honeycombing | 15/65.2% | 4/28.6% | 0.032 | 1/14.3% | 6/85.7% | 0.237 |

| Traction bronchiectasis | 15/65.2% | 4/28.6% | 0.032 | 1/14.3% | 6/85.7% | 0.237 |

| Scores | ||||||

| APACHE II | 19.3±12.3 | 16.5±5 | 0.198 | 14.3±3.2 | 18.9±7.3 | 0.352 |

| SAPS | 36.1±12.3 | 38.4±10.2 | 0.713 | 39±6.9 | 36.6±12.1 | 0.476 |

| NIV | 5/21.7% | 4/28.6% | 0.639 | 2/28.6% | 5/71.4% | 1 |

| IMV | 23/100% | 10/28.6% | 0.007 | 5/71.4% | 2/28.6% | 1 |

We found a high ICU and short term mortality rate, 62.2% and 50% respectively. These findings are consistent with the available literature, which indicates that progression and exacerbation of chronic ILD generally denotes a poor outcome once IMV has been instituted.4,5

Fibrotic ILD with CT scan evidence of fibrosis, defined as traction bronchiectasis and honeycombing was associated with a poor outcome. Traction bronchiectasis and honeycombing indicate advanced histopathological alterations, associated with increased lung stiffness, poorer alveolar-capillary gas exchange and greater vulnerability of the lung if IMV is used.3

There was a low rate of lung biopsy, probably reflecting concern about the risk of increased morbidity and mortality associated with this procedure.

The institution of IMV in these patients may raise philosophical questions and would be a procedure to debate, with individualized indications, mostly in cases where the disease is not very advanced or in lung transplant candidates. Physicians should discuss with patients and their relatives the level and degree of life support in case of clinical worsening and ICU admission with IMV should be needed.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.