The main aim of the study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety profile of Nivolumab, an immune-checkpoint-inhibitor antibody, in advanced, previously treated, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) patients, in a real world setting.

MethodsWe performed a retrospective, multicentre data analysis of patients who were included in the Portuguese Nivolumab Expanded Access Program (EAP). Eligibility criteria included histologically or citologically confirmed NSCLC, stage IIIB and IV, evaluable disease, sufficient organ function and at least one prior line of chemotherapy. The endpoints included Overall Response Rate (ORR), Disease Control Rate (DCR), Progression Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival (OS). Safety analysis was performed with the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), version 4.0, and immune-related Adverse Events (irAEs) were treated according to protocol treatment guidelines. Tumour response was assessed using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) version 1.1. Data was analysed using SPSS, version 21.0 (IBM Statistics).

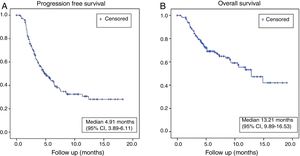

ResultsFrom June 2015 to December 2016, a total of 229 patients with advanced NSCLC were enrolled at 30 Portuguese centres. Clinical data were collected up to the end of July 2018. The baseline median age was 64 years (range 37-83) and the majority of patients were males (70.3%) and former/current smokers (69.4%). Patients with non-squamous histology predominated (88.1%), and 67.6% of the patients had received 2 or more prior lines of chemotherapy. Out of 229 patients, data was available for 219 patients (3 patients did not start treatment, while data was unavailable in 7 patients); of the 219 patients, 15.5% were not evaluated for radiological tumour assessment, 1.4% had complete response (CR), 21% partial response (PR), 31% stable disease (SD) and 31.1% progressive disease (PD). Thus, the ORR was 22.4% and DCR was 53.4% in this population. At the time of survival analysis the median PFS was 4.91 months (95% CI, 3.89–6.11) and median OS was 13.21 months (95% CI, 9.89–16.53). The safety profile was in line with clinical trial data.

ConclusionsEfficacy and safety results observed in this retrospective analysis were consistent with observations reported in clinical trials and from other centres.

Avaliar a eficácia e o perfil de segurança do Nivolumab, um anticorpo inibidor dos checkpoints imunológicos, em doentes com cancro do pulmão de células não pequenas (CPCNP) metastizado, previamente tratado, na prática clínica diária.

MétodosEstudo retrospectivo multicêntrico, de doentes com CPCNP incluídos no Programa de Acesso Precoce (PAP) do Nivolumab. Os critérios de inclusão eram CPCNP histologicamente ou citologicamente confirmados, estadio IIIB e IV, doença avaliável, boa função hepática e renal, e pelo menos um tratamento prévio de quimioterapia. Os objectivos principais eram a Taxa de Resposta Global (ORR), Taxa de Controlo da Doença (DCR), Sobrevivência livre de progressão (PFS) e Sobrevivência Global (OS). O perfil de segurança do fármaco foi avaliado de acordo com o National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), versão 4.0, e os efeitos adversos imuno-relacionados (irAEs) foram tratados de acordo com as normas de orientação clínica do protocolo. A avaliação da resposta foi efectuada usando a Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) versão 1.1. Os dados foram analisados com recurso ao SPSS, versão 21.0 (IBM Statistics).

ResultadosDe Junho 2015 a Dezembro 2016, um total de 229 doentes com CPCNP avançado foram incluídos no PAP em 30 Centros portugueses. Os dados clínicos foram recolhidos até ao final de Julho de 2018. A mediana de idade basal foi de 64 anos (intervalo 37-83) e a maioria dos pacientes era do sexo masculino (70,3%) e ex-fumadores ou fumadores (69,4%). Os doentes com histologia não-escamosa predominaram (88,1%) e 67,6% dos pacientes receberam 2 ou mais linhas de quimioterapia prévias. Foi possível recolher dados de 219 doentes (dos restantes 10, 3 não iniciaram o tratamento, e os dados de 7 doentes não estavam disponíveis). Destes 219 doentes, em 15,5% não foi possível fazer avaliação radiológica do tumor, 1,4% apresentaram resposta completa (RC), 21% resposta parcial (RP), 31% doença estável (SD) e 31,1% progressão da doença (DP). Assim, nesta população, a ORR foi de 22,4% e a DCR 53,4%. À data da análise de sobrevivência, a PFS mediana foi de 4,91 meses (IC 95%, 3,89–6,11) e a OS mediana 13,21 meses (IC 95%, 9,89–16,53). O perfil de segurança foi sobreponível aos dados dos ensaios clínicos.

ConclusõesOs dados de eficácia e segurança observados nesta análise retrospectiva foram concordantes com os dados dos ensaios clínicos e observados em outros estudos de vida real.

Worldwide, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among both men and women, with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounting for approximately 85% of all lung cancers, divided into non-squamous (70%) and squamous (30%) histologic subtypes.1 Patients with locally advanced and metastatic NSCLC have poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate <5%.2 Since the end of the 90s, chemotherapy has been the initial standard-of-care for patients with advanced NSCLC whose tumours do not harbour mutations sensitive to targeted therapies. The therapeutic landscape of NSCLChas shown great progress in recent years with the advent of immune-checkpoints inhibitors, leading to a significant improvement in patient life expectancy. These drugs modified the treatment standards, but data documenting real life experience are scarce. Nivolumab is a human IgG4 PD-1 immune-checkpoint-inhibitor antibody that blocks the interaction between PD-1 protein and its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2,3 which inhibits the immune response by limiting T cell proliferation and cytokine production.4 Nivolumab was the first checkpoint inhibitor to show a survival benefit in previously treated advanced squamous and non-squamous NSCLC, compared to docetaxel in two randomized trials, CheckMate 0175 and CheckMate 057.6 Nivolumab showed a significantly longer overall survival (OS) and a favourable safety profile in patients experiencing disease progression during or after platinum-based chemotherapy. Median OS was 9.2 months compared with 6.0 months in squamous NSCLC (CheckMate 017)5 and 12.2 months compared with 9.4 months in non-squamous NSCLC (CheckMate 057).6 Data on clinical effectiveness and safety of nivolumab in patients with poor performance status (PS) and in those with 70 years of age or older are scarce,7–12 because such patients are usually excluded from randomized clinical trials. Three studies that included these patient subgroups, CheckMate 153,13 CheckMate 16914 and CheckMate 17115 provided evidence that nivolumab tolerability is similar in all patient groups and that effectiveness is comparable in all age groups, but that patients with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS of 2 experience shorter OS.

The Portuguese Nivolumab expanded access programme (EAP) in advanced NSCLC provided an opportunity for patients to gain access to treatment during pharmaco-economical evaluation. In contrast to the inclusion criteria in controlled clinical trials, the eligibility criteria for the EAP were very broad, allowing the investigators to prescribe the use of nivolumab in a setting comparable to clinical practice. We present an analysis of the efficacy and safety of nivolumab in patients with advanced NSCLC enrolled in the EAP in Portugal. The main aim of this study is to analyse the characteristics, the treatment outcomes and safety of patients with advanced stage NSCLC treated with nivolumab in second or further lines in our clinical practice and correlate the results with clinical trial outcomes. Moreover, a secondary aim is to perform subgroup analysis in order to identify predictive biomarkers.

MethodsPatientsThe EAP population comprised patients aged ≥18 years with histologically or citologically confirmed stage IIIB or IV NSCLC (squamous and non-squamous) that had progressed or recurred after at least one prior systemic treatment for advanced or metastatic disease. Patients were required to have an ECOG Performance Status of 0, 1 or 2; completion of prior chemotherapy, tyrosine kinase inhibitors or palliative radiotherapy, 2 weeks before starting nivolumab; resolution of all adverse events (AEs) to grade 1 (NCI CTCAE: National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4) at baseline; adequate organ function and a life expectancy of at least 6 weeks. Exclusion criteria included active brain metastasis, positive test for hepatitis B or C virus indicating acute or chronic infection, known history of testing positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a severe autoimmune disease and patients with a condition requiring systemic treatment with either corticosteroids (>10mg daily prednisolone equivalent) or other immunosuppressive medications.

The treatment plan was explained in detail and all patients signed and dated a written informed consent form provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb. The study was approved by the INFARMED (Portuguese National Authority of Medicines and Health Products) and was executed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice, and local ethical and legal requirements.

Study design and treatmentWe retrospectively collected clinical data for the eligible patients enrolled in the Nivolumab EAP at 30 Portuguese cancer centres from June 2015 to December 2016. All patients included were followed until the end of data collection on July 2018. The evaluation included a review of demographic and tumour characteristics: age, gender, smoking status, performance status, clinical stage, histology and number of previous treatments. All patients included in the analysis received at least one cycle of nivolumab at the standard dose of 3mg per kilogram of body weight (60-minute intravenous infusion) every 2 weeks for ≤24 months. The treatment was continued depending on disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, completion of permitted cycles (24 months) or withdrawal of consent. Dose escalation or reduction was not allowed, but treatment could be delayed in the event of toxicity. Treatment beyond progression was allowed if, in the investigator’s opinion, the patient was deriving clinical benefit, in the absence of rapid disease progression, severe toxicity or performance status escalation. Computed tomography (CT) based evaluation was performed around every 12 weeks.

AssessmentsDemographic analysis included all patients in EAP. Safety was monitored by AE assessment, physical examination and laboratory tests. Investigators graded AEs according to the NCI CTCAE, version 4, and determined their causal relationship to treatment; for specific immune-related AEs, the protocol specific treatment guidelines were used. The EAP had no pre-specified end-points. Safety analysis included all patients treated (those who received at least one dose of study drug). Collected efficacy data included investigator-assessed objective tumour response, date of progression and survival information. Tumour response was assessed using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) version 1.1. Efficacy analysis included all evaluable patients and the exploratory assessments analysed were: Overall response rate (ORR; defined as the combined rates of complete and partial responses), disease control rate (DCR; defined as the combined rates of complete response, partial response and stable disease), progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). PFS was defined as the time from date of first nivolumab treatment until date of first evidence of disease progression or death (whichever occurred first). The OS was also calculated from the first day of administration of nivolumab treatment until the patient’s death or last date of follow-up.

Statistical analysisA descriptive statistical analysis was performed, including central tendency and dispersion parameters for the quantitative variables and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. Categorical variables were presented by numbers and percentiles, medians and ranges were reported for continuous variables. The Kaplan-Meyer method with a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) was used to estimate PFS and OS. Patients who were alive, without disease progression were censored at the time of last follow-up. Patients lost to follow-up were censored at the time of last contact. Patients who died because of their lung cancer before any radiological response evaluation were considered to have progressive disease at the time of death. A univariate analysis to test for differences between groups was performed using the log-rank test, followed by a multivariate analysis by Cox regression model to identify prognostic factors associated with OS. Univariate and multivariate hazard ratios were reported with a 95% CI. Statistical significance was set at p less than 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS Statistical Software, version 21.0 (IBM_SPSS). We used BiostatXL MIX 2.0 (available at: http://www.meta-analysis-made-easy.com) to compute sub-group analysis estimates.

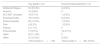

ResultsDemographic and tumour characteristics and treatmentFrom June 2015 to December 2016, a total of 229 patients with advanced NSCLC were enrolled at 30 Portuguese centres. Of the 229 patients, data was available for analysis in 219 patients (3 patients did not start treatment, and unavailable data in 7 patients); all patients included in the analysis received at least one cycle of nivolumab. The median number of nivolumab cycles administered was 14 (range, 1–52). The median age at the start of the treatment was 64 years (range 37–83) and the majority of patients were males (n=154; 70.3%). Most cases were former/current smokers (n=152; 69.4%). Patients with non-squamous histology predominated (n=193; 88.1%). All patients had previously received at least one platinum-based therapy and 84 (38.4%) patients received 2 prior systemic lines of therapy; 25 (11.4%) three lines, 21 (9.6%) four lines; 18 (8.2%) more than four lines of treatment. According to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status score (ECOG-PS), at the start of treatment 26 (11.9%) patients had an ECOG-PS 0, 164 (74.9%) had ECOG-PS 1 and 29 (13.2%) had ECOG-PS 2. In our cohort, no routine tumour staining for PD-L1 was done, because at the time of the EAP it was not part of routine clinical practice nor was it an inclusion criteria for EAP. See Table 1 for a comprehensive list of population baseline characteristics, stratification factors and prior therapy.

Baseline characteristics, stratification factors and prior therapy (N=219).

| Age (years) | ||

| Median (Range) | 64 (37–83) | |

| N (%) | ||

| Age ≥75 | 33 (15%) | |

| Gender | Male | 154 (70.3%) |

| ECOG performance-status score | ||

| 0 | 26 (11.9%) | |

| 1 | 164 (74.9%) | |

| 2 | 29 (13.2%) | |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current | 63 (28.8%) | |

| Former smoker | 89 (40.6%) | |

| Never smoker | 50 (22.8%) | |

| Unknown | 17 (7.8%) | |

| No. of prior systemic regimens | ||

| 1 | 71(32.4%) | |

| 2 | 84 (38.4%) | |

| 3 | 25 (11.4%) | |

| 4 | 21 (9.6%) | |

| >4 | 18 (8.2%) | |

| Stage | ||

| IIIb | 18 (8.2%) | |

| IV | 201 (91.8 %) | |

| Histology | ||

| Non-squamous | 193 (88.1%) | |

| Squamous | 26 (11.9%) | |

With a median follow-up of 17.1 (1–34.1) months, of the 219 patients enrolled, the best overall response in the total patient population was complete response (CR) in 3 (1.4%) patients, partial response (PR) in 46(21%) patients, stable disease (SD) in 68 (31%) patients and progressive disease (PD) in 68 (31.1%) patients. No evaluation could be carried out on 34 patients (15.5%) because of poor general condition or early death. Thus, the ORR was 22.4% and DCR was 53.4%. At the time of survival analysis, the median PFS was 4.91 months (95% CI, 3.89–6.11) and median OS was 13.21 months (95% CI, 9.89–16.53) in the overall population (Fig. 1). The 6, 12- and 18-month OS rates were 71%, 56.5% and 43% respectively.

SafetyOf the 178 patients (81.3%) who discontinued treatment, the reasons for discontinuation were progressive disease in 116 patients (52.2%), death in 23 patients (10.5%), adverse events in 28 (12.5%) and other reason in 22 (10%). A total of 136 patients had at least one adverse event in a total of 175 treatment–related AE’s of any grade, among which 28 led to treatment discontinuation, listed in Table 2. The most common toxicities reported were asthenia/fatigue, 41 events (23.4%), and endocrinopathy, 25 events (14.3%). Discontinuation of the study drug due to treatment-related AEs occurred in 28 patients (16%) in total, 10 of them (5.7%) due to pneumonitis and 6 (3.4%) due to colitis. AEs were managed using protocol-defined toxicity management algorithms.

Treatment-related adverse events.

| Any grade n (%) | Discontinued treatment n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Asthenia/Fatigue | 41 (23.4%) | 4 (2.4%) |

| Anemia | 12 (6.9%) | 0 |

| ALT/AST increase | 10 (5.7%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Diarrhea/Colitis | 18 (10.2%) | 6 (3.4%) |

| Endocrinopathy | 25 (14.3%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Pain | 9 (5.3%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Pyrexia | 2 (1.1%) | 0 |

| Pneumonitis | 17 (9.7%) | 10 (5.7%) |

| Rash | 20 (11.4%) | 0 |

| Other | 21 (12.0%) | 5 (3%) |

| Total events (n=175) | Total events (n=28; 16.0%) |

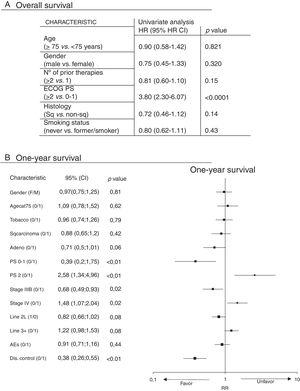

Subgroup analyses were performed for OS (Fig. 2). In the univariate analysis, ECOG PS score was the only factor which significantly correlated with overall survival (Fig. 2A) by comparing patients who had an ECOG PS of 0–1 with those with an ECOG PS of 2, with a Hazard Ratio (HR) of 3.80 (95%CI: 2.30 to 6.07), p<0.0001). There were no statistically significant differences in gender (p=0.320), age (patients ≥75 vs. <75 years; p=0.821), histology (squamous vs. non-squamous, p=0.14), or number of prior therapy lines (≥2 vs. 1, p=0.15) and smoking status (never vs. former/smoker, p=0.43). In the multivariate analysis, ECOG PS score remained the only factor significantly related to overall survival (p<0.0006). PS 0-1, Stage IIIB and Disease Control (DC) with nivolumab increase the probability of surviving at least one year, unlike PS 2 and Stage IV (Fig. 2B).

DiscussionIn our real-world population, median OS was 6.9 months (95% CI, 3.6–10.2) and 13.8 months (95% CI, 10.8–16.9) in squamous and non-squamous cell histological subtype, respectively. This compares favorably with the median overall survival of 12.2 months (95% CI, 9.7–15.0 months) for patients with non-squamous cell NSCLC in CheckMate 0576 trial. Comparison with CheckMate 0175 is more difficult, since only 11.9% of our patients had squamous NSCLC. The median PFS observed in real world data for non-squamous NSCLC was 6.1 months, superior to the 2.3 months reported in the clinical trial. One possible reason is that in clinical trials, computerised tomographies (CTs) are performed more frequently and this could lead to an earlier detection of patients’ progression. In real life, CTs are often delayed due to time and workload constraints associated with our healthcare system. In our series, ECOG PS seems to be the most important survival-related variable which demonstrated a negative correlation in both univariate and multivariate analysis. Importantly, OS of patients with ECOG PS 0-1 in our series of 12.6 months (95% CI, 9.3–16.0 months) is in line with the literature data, confirming the results of CheckMate 0175 and CheckMate 0576 trials. On the other hand, overall survival of patients with ECOG PS=2 was much worse, 3.1 months (95% CI, 0.4–5.6). In the CheckMate trial 153,13 efficacy and safety of nivolumab in older patients and patients with PS 2 has already been reported, nivolumab was effective and well tolerated in PS 2 patients, with no new safety concerns and a median OS of 3.9 months (95% CI, 3.1–6.3) and 1year OS rate of 23% (95% CI, 16–32). Importantly, in our series, no negative correlation between the patients’ age and OS was demonstrated implying that elderly with good ECOG PS derive the same benefit from nivolumab as their younger counterparts. These findings are in accordance with the results of CheckMate 057,6 demonstrating similar benefit across all age subgroups that exist in real world.

Overall, nivolumab was well tolerated, with a favourable AE profile and observed AEs consistent with those previously reported. Among registered adverse events, grades were very seldom documented except those leading to treatment discontinuation.

ConclusionWe have shown a clinically meaningful survival benefit in nivolumab treated patients, with a favourable safety profile. These clinically relevant data support the use of nivolumab as a treatment option for previously treated advanced NSCLC patients.

FundingNivolumab was provided to patients by Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) in the context of the Expanded Access Program. Medical writing was funded as an unrestricted grant by BMS, and as such BMS was not involved in collection, analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript drafting or submission.

Conflict of interestIn relation to this article, the authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors thank the patients and their families for making this expanded access program possible, as well as all the clinicians from the various sites who participated in the Portuguese cohort of the nivolumab expanded access program for NSCLC.

All authors contributed to the review and to the decision to submit this manuscript for publication. The authors are listed in alphabetic order, except the first one (corresponding author) and the last one (final reviewer).

Medical writing was provided by Joana Dias, MSc.