Monitored physical activities in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) have been shown to improve physical performance, endurance and cardiopulmonary function and may be assessed by the 6-min walk test (6MWT). We aimed to evaluate the long-term results of the 6MWT after a rehabilitation protocol employed before surgical correction for AIS.

MethodsThis prospective randomized clinical trial studied the impact of a 4-month pre-operative physical rehabilitation protocol on post-operative cardiopulmonary function and physical endurance, by using the 6MWT, in patients with AIS submitted to surgical correction, comparing them to matched controls without physical rehabilitation. Studied variables were heart and respiratory rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, peripheral blood oxygen saturation, Borg score, and distance walked. Patients were assessed at baseline, after 4 months of rehabilitation, and 3, 6 and 12 months post-operatively.

ResultsA total of 50 patients with AIS were included in the study and allocated blindly, by simple randomization, into either one of the two groups, with 25 patients each: study group (pre-operative physical rehabilitation) and control group. The physical rehabilitation protocol promoted significant progressive improvement in heart and respiratory rate, peripheral blood oxygen saturation, distance walked, and level of effort assessed by the Borg scale after surgery.

ConclusionsPost-surgical recovery, evaluated by 6MWT, was significantly better in patients who underwent a 4-month pre-operative physical rehabilitation protocol.

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is a lateral deviation of the spine. It is defined as a lateral curvature greater than 10 degrees of unknown cause that progressively distorts the anatomy of the thorax, and with vertebral rotation.1–6 It affects 2–4% of children between 10 and 16 years of age.6 The prevalence of curves greater than 30 degrees is approximately 0.2%, and of curves greater than 40 degrees is approximately 1% of the children between 10 and 16 years of age.1–6 It corresponds to about 80% of the scoliotic deformities of the spine in the adolescent population, and over 50% of the patients present a thoracic curve.1–5 A number of different factors, isolated or combined, have been associated to AIS, such as a deviation in the growth pattern of the spine, neuromuscular or connective tissue abnormalities, asymmetrical growth or lateralization of the sagittal configuration of the spine, as well as hereditary factors.1–5 It is thought to be a multigene dominant condition, with variable phenotypic expression.6

Distortion of the three thoracic dimensions in patients with AIS results in a syndrome with pulmonary function abnormalities, pain and physical deformity.2–4 Pulmonary function testing (PFT) in these patients shows a reduced vital capacity, combining a drop in total pulmonary capacity, reduced arterial oxygenation, and alveolar hypoventilation.2 The pulmonary abnormalities may cause ventilatory restrictions and lead to exercise intolerance, mostly due to a decreased capacity to offer oxygen to the muscles undergoing greater demand.7–9

There are a number of tests designed to assess the inability to perform physical activities. The 6-min walk test (6MWT) has been used to assess physical and cardiorespiratory status of patients presenting with moderate to severe pulmonary and cardiac abnormalities submitted to medical procedures, allowing correlations with morbidity and mortality of specific diseases.7–9 Assessment of the distance walked is an expressive measurement of physiological function and an important component of overall quality of life, since walking is directly related to daily life activities.9 The 6MWT presents a stronger correlation with heart rate (HR), peripheral blood saturation (SpO2), and dyspnea than other physical exertion tests, such as the stationary bicycle and treadmill, both in healthy individuals and in patients with functional respiratory and pulmonary abnormalities.10

The 6MWT significantly correlated to forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) in a study of healthy adolescents aged 12–16 years,11 and in children aged 3–16 years it successfully determined submaximal functional capacity.12 Patients with AIS usually present with reduced aerobic capacity that is possibly related to the ventilatory restriction observed in the reduced forced volume of these patients.13,14 In the first phase of the current study the authors used the 6MWT to evaluate the results of a physical therapy protocol on the pre-operative cardiopulmonary performance of a group of surgical candidates with AIS comparing them to matched controls that did not receive physical rehabilitation, finding that patients submitted to the protocol presented significant reduction in all vital signs and a significant increase in the distance walked when compared to baseline parameters and to controls.7

Considering the improved performance in the 6MWT of patients with AIS submitted to the abovementioned pre-operative rehabilitation protocol,7 the current study was designed to evaluate the long-term results of this regimen following surgical correction of the spinal deformity.

Methods and materialsStudy design and ethicsThis prospective randomized clinical trial was carried out at a tertiary teaching hospital from January 2008 to January 2009. All participants diagnosed with AIS at the Orthopedics Department of the Institution who consented to participate in the study after careful clarification of the objectives and techniques involved, and those who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included. The Institutional Review Board for Ethics in Clinical Studies approved this study (protocol # 235/09).

Inclusion criteria were: a diagnosis of AIS with a thoracic curve greater than 45 degrees; being a candidate for surgery; aged between 10 and 18 years; able to complete the 6MWT. Exclusion criteria were: present or past history of pulmonary, cardiac, myo-articular or neurological diseases.

Participants were randomized by opaque, sealed envelopes, into one of the two groups: Group I – patients with AIS who were submitted to the physical rehabilitation protocol, and Group II – patients with AIS who were not submitted to the rehabilitation protocol (controls). A total of 50 patients were included, 25 in each group.

The sample size was calculated for simple random sampling, using a confidence interval of 95 (95%) and 5% error for infinite sample.

Exercising protocolPatients in Group I underwent a 4-month pre-operative physical rehabilitation program, modified from Bouchard and Shepard15 and Covey et al.16 Sessions were three times a week (every other day) and 60-min long, consisting of a 10-min warm-up (stretching and low grade aerobic exercises, such as, slow and progressive walks); 40-min aerobic work-out on the treadmill or stationary bicycle working at 60–80% of the maximum heart rate; and a final 10-min cool-down with relaxation (stretching and low energy aerobic exercises followed by relaxation techniques).7 This protocol was chosen because it had been found to be effective in patients with pulmonary diseases before,17 and it was already tested by our team.14 The participants were closely supervised by the same physical therapist, who was not present during the 6MWT evaluation.

SurgeryAll AIS participants in this study, in both groups, had indication for and underwent surgical correction of the spine. Vertebral arthrodesis was performed with the same instrumentation techniques for all of them, with a posterior longitudinal approach and iliac autologous graft.

Clinical and 6-min walk test (6MWT) evaluationsThe spinal curves were assessed by plain standing radiographs in the antero-posterior (AP) and lateral views using Cobb's method to determine the angle of the spinal deformity.18 Clinical evaluation of the hump was performed with the Adam's test.2

The 6MWT was carried out according to the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society (ATS),8 before and after the period encompassing the rehabilitation program, as well as 3, 6 and 12 months after surgical correction of the spinal deformity in both groups. The 6MWT consists of a free walk during 6min as fast as possible across a flat surfaced 30-m long corridor graded by the meter. Baseline (pre-test) monitoring of arterial blood pressure (BP), heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), and level of effort based on the Borg scale8 were obtained for all participants. At completion of the 6min, the total distance walked was recorded and the same parameters were re-assessed.

Thus, participants were assessed at five different periods: baseline (upon entering the study, all the participants), pre-operatively (study group after 4-month re-habilitation and controls at the same period), and post-operatively at 3, 6, and 12 months (all the participants).

Statistical analysisDescriptive analysis of the quantitative variables is presented in tables with summary measures of mean profiles. Initially, demographic and angular variables (obtained from the radiographic evaluation) were compared using the Student t test or Mann–Whitney test. Comparison of variables between groups over time was performed by means of model analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures. In some situations (if the interaction between group and time effect was statistically significant), post hoc tests (multiple comparisons by Student t tests with Bonferroni correction) were used to compare groups at each time period.

The significance level is 5%, except in the analysis of multiple comparisons (post hoc) in which the significance level adjusted to be used is 1%.

ResultsAll recruited participants were followed up until the end of this study (there was no loss in follow-up). No patient needed any change in the rehabilitation protocol during the study period. Group I (study) was comprised of 25 patients, with a mean age of 14.12 years (SD+1.83), a mean scoliosis angle of 64.28 degrees (SD+18.62), ranging from 45 to 115 degrees; a mean kyphosis angle of 35.96 degrees (SD+12.36), ranging from 10 to 72 degrees; and a mean Adam's score of 42.04 (SD+14.40). Group II (control) also had 25 patients, with a mean age of 13.56 years (SD+2.02), a mean scoliosis of 65.56 degrees (SD+14.68), ranging from 46 to 110 degrees; a mean kyphosis of 35.52 degrees (SD+14.52), ranging from 8 to 62 degrees; and a mean Adam's score of 41.92 (SD+12.56) ranging from 8 to 67.

At baseline, there were no significant differences between groups for the variables age (p=0.31), scoliosis (p=0.29), kyphosis (p=0.90), and Adam's score (p=0.97).

Comparisons between Groups I and II showed no statistically significant differences on baseline 6MWT results, evidencing homogeneity between groups. There were no statistical differences between baseline and immediate pre-operative 6MWT results in this group of control individuals.

Four months after physical rehabilitation, comparison between baseline and post physical rehabilitation 6MWT results for Group I showed a statistically significant increase in the distance walked (p<0.001).

Tables 1–7 depict the ANOVA multivariate analysis of the repeat measures and confidence intervals of the 6MWT variables: distance walked, heart and respiratory rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, peripheral blood oxygen saturation and Borg scale.

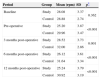

Mean heart rate (HR) of patients with AIS submitted to surgical repair comparing the study group (submitted to pre-operative rehabilitation) to controls at baseline (upon entering the study), pre-operatively, after 4 months (post-rehabilitation for the study group), and 3, 6, and 12 months post-operatively (all participants).

| Period | Group | Mean (bpm) | SD | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Study | 115.24 | 7.95 | 0.853 |

| Control | 114.64 | 13.97 | ||

| Pre-operative | Study | 97.76 | 11.52 | <0.001 |

| Control | 117.08 | 9.48 | ||

| 3 months post-operative | Study | 111.12 | 8.72 | <0.001 |

| Control | 123.56 | 8.15 | ||

| 6 months post-operative | Study | 106.40 | 7.33 | <0.001 |

| Control | 120.00 | 12.05 | ||

| 12 months post-operative | Study | 105.64 | 9.05 | <0.001 |

| Control | 120.40 | 10.19 |

bpm=beats per minute; SD=standard deviation.

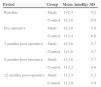

Mean respiratory rate (RR) of patients with AIS submitted to surgical repair comparing the study group (submitted to pre-operative rehabilitation) to controls at baseline (upon entering the study), pre-operatively, after 4 months (post-rehabilitation for the study group), and 3, 6, and 12 months post-operatively (all participants).

| Period | Group | Mean (rpm) | SD | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Study | 28.08 | 3.37 | 0.362 |

| Control | 28.88 | 2.74 | ||

| Pre-operative | Study | 25.20 | 3.87 | <0.001 |

| Control | 29.96 | 3.47 | ||

| 3 months post-operative | Study | 28.52 | 3.73 | 0.001 |

| Control | 32.00 | 2.86 | ||

| 6 months post-operative | Study | 26.12 | 3.61 | <0.001 |

| Control | 31.64 | 3.34 | ||

| 12 months post-operative | Study | 25.24 | 3.79 | <0.001 |

| Control | 30.92 | 3.19 |

rpm=respiration per minute; SD=standard deviation.

Mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) of patients with AIS submitted to surgical repair comparing the study group (submitted to pre-operative rehabilitation) to controls at baseline (upon entering the study), pre-operatively, after 4 months (post-rehabilitation for the study group), and 3, 6, and 12 months post-operatively (all participants).

| Period | Group | Mean (mmHg) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Study | 112.4 | 5.2 |

| Control | 112.8 | 5.4 | |

| Pre-operative | Study | 112.0 | 5.0 |

| Control | 112.4 | 6.0 | |

| 3 months post-operative | Study | 113.6 | 5.7 |

| Control | 111.6 | 4.7 | |

| 6 months post-operative | Study | 113.6 | 5.7 |

| Control | 113.2 | 4.8 | |

| 12 months post-operative | Study | 112.4 | 5.2 |

| Control | 112.0 | 5.0 |

SD=standard deviation.

Mean diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of patients with AIS submitted to surgical repair comparing the study group (submitted to pre-operative rehabilitation) to controls at baseline (upon entering the study), pre-operatively, after 4 months (post-rehabilitation for the study group), and 3, 6, and 12 months post-operatively (all participants).

| Period | Group | Mean (mmHg) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Study | 72.0 | 6.5 |

| Control | 72.4 | 5.2 | |

| Pre-operative | Study | 70.8 | 6.4 |

| Control | 72.4 | 5.2 | |

| 3 months post-operative | Study | 74.0 | 5.8 |

| Control | 72.4 | 5.2 | |

| 6 months post-operative | Study | 73.6 | 6.4 |

| Control | 73.2 | 5.6 | |

| 12 months post-operative | Study | 71.2 | 6.7 |

| Control | 72.0 | 5.8 |

SD=standard deviation.

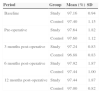

Mean peripheral blood oxygenation (SpO2) of patients with AIS submitted to surgical repair comparing the study group (submitted to pre-operative rehabilitation) to controls at baseline (upon entering the study), pre-operatively, after 4 months (post-rehabilitation for the study group), and 3, 6, and 12 months post-operatively (all participants).

| Period | Group | Mean (%) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Study | 97.16 | 0.94 |

| Control | 97.40 | 1.15 | |

| Pre-operative | Study | 97.64 | 1.82 |

| Control | 97.60 | 1.12 | |

| 3 months post-operative | Study | 97.24 | 0.83 |

| Control | 96.88 | 0.83 | |

| 6 months post-operative | Study | 97.92 | 1.87 |

| Control | 97.44 | 1.00 | |

| 12 months post-operative | Study | 97.44 | 1.87 |

| Control | 97.00 | 0.82 |

SD=standard deviation.

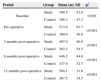

Mean Borg effort scale (Borg) of patients with AIS submitted to surgical repair comparing the study group (submitted to pre-operative rehabilitation) to controls at baseline (upon entering the study), pre-operatively, after 4 months (post-rehabilitation for the study group), and 3, 6, and 12 months post-operatively (all participants).

| Period | Group | Mean | SD | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Study | 16.16 | 0.99 | 0.809 |

| Control | 16.08 | 1.32 | ||

| Pre-operative | Study | 13.40 | 1.80 | <0.001 |

| Control | 16.12 | 1.33 | ||

| 3 months post-operative | Study | 15.16 | 0.75 | <0.001 |

| Control | 17.32 | 1.28 | ||

| 6 months post-operative | Study | 14.76 | 1.09 | <0.001 |

| Control | 16.72 | 1.10 | ||

| 12 months post-operative | Study | 13.80 | 1.47 | <0.001 |

| Control | 16.12 | 1.09 |

SD=standard deviation.

Mean distance walked in meters (m) during 6min (6MWT) of patients with AIS submitted to surgical repair comparing the study group (submitted to pre-operative rehabilitation) to controls at baseline (upon entering the study), pre-operatively, after 4 months (post-rehabilitation for the study group), and 3, 6, and 12 months post-operatively (all participants).

| Period | Group | Mean (m) | SD | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Study | 399.5 | 41.0 | 0.926 |

| Control | 398.3 | 47.2 | ||

| Pre-operative | Study | 513.6 | 63.7 | <0.001 |

| Control | 390.9 | 36.8 | ||

| 3 months post-operative | Study | 407.0 | 40.9 | <0.001 |

| Control | 292.2 | 54.5 | ||

| 6 months post-operative | Study | 446.2 | 44.6 | <0.001 |

| Control | 337.6 | 32.7 | ||

| 12 months post-operative | Study | 504.1 | 31.6 | <0.001 |

| Control | 367.5 | 34.5 |

SD=standard deviation.

It is possible to observe that the pressures SBP and DBP (Tables 3 and 4) behave in a similar way between groups and over time (no interaction effect: p=0.750 and p=0.349, respectively). Incidentally, there is no effect of time (p=0.340 and 0.085, respectively) and no significant difference between groups (p=0.340 and 0.903). For SpO2 (Table 5), the average behavior of the groups over time is equal (p=0.191). Therefore, when comparing the groups, we see that there is no difference between them (p=0.472). There is a time effect (p=0.006), i.e. SpO2 varies over time, but it is similar in both groups.

For the other variables evaluated in the 6MWT (HR, RR, distance and Borg), the interaction between group and time is significant (Tables 1–7, p<0.001).

When checking at which moments the groups are different, we observe that, for all variables described above, on average, the study group has lower values than the control group from the preoperative period on, except for the distance walked, which increases (p<0.001).

DiscussionPatients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) frequently evolve with reduced vital capacity, and a drop in total pulmonary capacity associated to deficient arterial oxygenation and alveolar hypoventilation as a consequence of the tridimensional physical deformities of the spine.1,2,4,13 This was also observed in the present study, in which the patients with AIS had much lower baseline evaluations than would be expected for their age. This reduced respiratory capacity influences the final distance walked in 6MWT.7 Such deficiencies increase morbidity and are directly related to the severity of the curve.2 Volume changes are also a direct consequence of the decrease in blood oxygen13 and interfere with the capacity to adapt to greater physical challenge, such as that required for walking fast, leading to a progression in restriction to physical activities.19–21 The respiratory changes, however, do not seem to be directly related to the severity of the spinal curve but most likely a consequence of a combination of factors, such as the morphology, the site and the number of vertebra involved in the curve.5 In the first phase of the current study no correlation could be established between the angle of the scoliosis and the distance walked on 6MWT.7

Monitored physical activities in patients with respiratory restrictions have been shown to improve physical performance, endurance and cardiopulmonary function.15,22 The pre-operative physical rehabilitation protocol proposed here revealed a significant drop in RR, HR, and Borg scores, associated to an increase in SpO2 and in the distance walked on the 6MWT that persisted after corrective surgery. Inversely, patients with AIS who did not undergo physical rehabilitation (control group) had an increase in RR, HR and Borg scores, and a drop in SpO2.

An increase in tolerance to dynamic exercise, expressed both by increments in maximum performance and endurance, can be explained by a number of factors, one of which is the real improvement in aerobic power offered by training.23 Unlike other functional tests that are performed during rest the 6MWT does not underestimate the patient's capacity to perform physical activities.10 Thus, by quantifying physiological responses, physical testing via the 6MWT facilitates the design of a personalized physical activity program.20

The pre-operative physical therapy protocol proposed in the current study promoted significant progressive improvement in heart and respiratory rate, peripheral blood oxygen saturation, distance walked in the 6MWT, and level of effort assessed by the BORG scale after surgical correction of AIS. The study group also performed better than controls throughout the post-operative period. Our results suggest an interesting hypothesis to be evaluated: assuming that treated patients have had good performance even after one year after surgery, it is possible that they have felt able to exercise during this year, and this was reflected in the difference compared to controls, which could only walk shorter distances. It is reasonable to assume that the benefit that was obtained by the study group with a four-month exercising protocol before surgery would increase if the exercising was applied also after recovering from surgery – but this would be the subject of another study.

Patients submitted to a pre-operative rehabilitation protocol recovered baseline respiratory and cardiac parameters faster than controls, achieving the same values on the 6MWT one year after surgery as those at completion of the protocol, before surgery.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingThis work was supported by a grant from the São Paulo State Research Foundation [FAPESP# 07/54024-7].