We aimed to build a national consensus to optimize the use of oral corticosteroids (OCS) in severe asthma in Portugal.

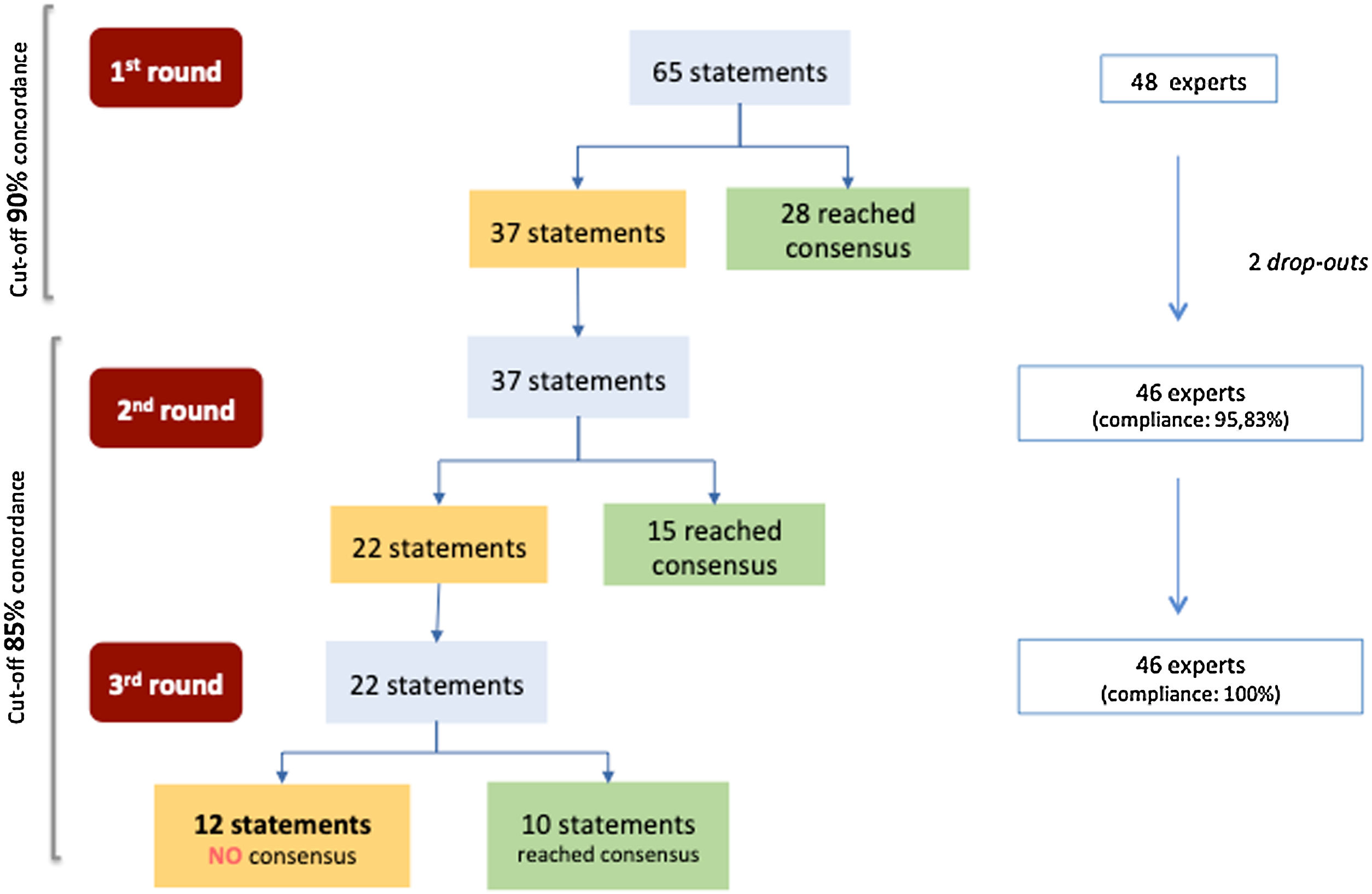

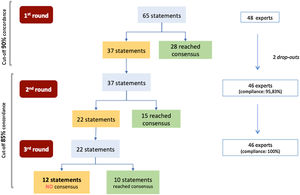

Material and methodsA modified 3-round Delphi including 65 statements (topics on chronic systemic corticotherapy, therapeutic schemes, asthma safety and monitoring) was performed via online platform (October-November 2019). A five-point Likert-type scale was used (1-‘strongly disagree’; 5-‘strongly agree’). Consensus threshold was established as a percentage of agreement among participants ≥90% in the 1st round and ≥85% in the 2nd and 3rd rounds. The level of consensus achieved by the panel was discussed with the participants (face-to-face meeting).

ResultsForty-eight expert physicians in severe asthma (specialists in allergology and pulmonology) participated in the study. Almost half of the statements (28/65; 43.1%) obtained positive consensus by the end of round one. By the end of the exercise, 12 (18.5%) statements did not achieve consensus. Overall, 87% of physicians agree that further actions for OCS cumulative risk assessment in acute asthma exacerbations are needed. The vast majority (91.7%) demonstrated a favorable perception for using biological agents whenever patients are eligible. Most participants (95.8%) are more willing to accept some degree of lung function deterioration compared to other outcomes (worsening of symptoms, quality of life) when reducing OCS dose. Monitoring patients’ comorbidities was rated as imperative by all experts.

Conclusions: These results can guide an update on asthma management in Portugal and should be supplemented by studies on therapy access, patients’ adherence, and costs.

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways that leads to wheezing, dyspnea, cough, and breathing difficulties as a consequence of generalized airway obstruction. In Portugal, the overall prevalence of asthma is around 10.5% (95% CI 9.5–11.6) of the population.1 There are different forms (phenotypes) of this condition, with different clinical features, including comorbidities, severity, treatment response and rates of acute exacerbations.2

Asthma control represents a main goal for the management of the disease and the impairment of patient’s quality of life is now considered a serious outcome in clinical trials and thus should be routinely evaluated by validated questionnaires.3 Patients with mild to moderate asthma are usually treated with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), sometimes at higher doses and associated with long-acting beta-agonists (LABA) or other therapies. If necessary, in a flare-up where treated adults do not respond to a four-time increase in baseline dose of ICS, oral corticosteroids (OCS) may be used for short-term periods., this corresponds to 40−50 mg of prednisone or equivalent for 5–7 days.4–6

Severe asthma occurs in 5-10% of patients and is often characterized by an insufficient response to ICS (i.e. refractory to conventional therapy), especially in some subsets of patients (e.g. obese), where the severity might ameliorate with specific strategies.7–10 These patients contribute to 50-60% of asthma costs and are responsible for most of the hospitalizations, admissions to emergency services and deaths from asthma.4–6 In Portugal, the annual cost of patients with asthma has a significant impact on the National Health System which is mainly associated with emergency services (30.7%) and treatments (37.4%). For uncontrolled asthmatics, the annual cost exceeds twice the costs of controlled patients.11

Currently, in severe patients without disease control due to frequent asthma symptoms or frequent exacerbations despite optimal treatment, the additional use of OCS, or even biologic agents (monoclonal antibodies) represent therapeutic alternatives. As reported in the SANI registry and also in a French study, over 60% of patients with severe asthma are on regular oral corticosteroid treatment.12–14 Low-dose OCS (≤ 7.5 mg/day of prednisone equivalent) combined with other therapies can be effective for some adults with severe asthma (evidence level D); but it is often associated with considerable adverse effects (evidence level B), which may influence patient’s quality of life and augment treatment costs.4,5,15 A systematic review published by Cochrane Collaboration (18 clinical trials; n = 2438 patients), concluded that the evidence on the best treatment scheme is still weak (whether lower dose or short-term regimens of OCS in asthma are less effective/safe than those with higher doses or prolonged regimens).16 Patients with severe asthma and T2-type inflammation respond to OCS and often require high and continuous dosages, contrary to T2-low asthma patients who have poor responsiveness to corticosteroid treatment. It was not until recently, in the era of widespread corticosteroid treatment for all patients with asthma, that it became evident that not all patients respond equally well to this treatment approach.17,18 In this context, it can be assumed that the chronic use of OCS in asthma has been gradually replaced by therapies that target specific inflammatory pathways involved in the pathogenesis of asthma that are already available such as the biologic agents for patients with T2-type inflammation.19,20

Thus, given the severity of asthma along with an unclear treatment algorithm for patients with different phenotypes, the overuse of corticosteroids in practice and the diversity of healthcare settings dealing with asthma patients, we aimed to build a national consensus towards the optimization of the use of OCS in adults with severe asthma.

Material and methodsStudy designThis study was designed as a modified 3-round Delphi exercise21,22 to obtain possible agreement on the topic of optimizing the use of oral corticosteroids in adults with severe asthma, among a broad panel of medical experts in asthma.

The scientific committee comprised six experts with experience in the treatment of severe asthma, with different backgrounds, namely pulmonology and immunoallergology, and one epidemiologist. The expert panel selected by the scientific committee consisted of 48 physicians (specialists in allergology and pulmonology), from public and private institutions (with clinical and academic expertise in the management of asthma), and with a wide distribution at national level to capture any regional specific aspects (North, Center and South Portugal). Because the survey was completed anonymously and no personal data were collected, institutional review board approval was not necessary. The research assistance team, which directed and oversaw the entire process, was responsible for the distribution and analysis of the questionnaires.

Delphi rounds and consensus meetingThe Delphi questionnaire was developed by the scientific committee and initially included 65 statements (items), formulated in Portuguese, grouped into three main topics: (1) Chronic Systemic Corticotherapy (CSC) in Asthma (n = 19 items); (2) Therapeutic Schemes of Systemic Corticotherapy in Crisis and Maintenance (n = 26 items); (3) Asthma Safety and Monitoring (n = 20 items).

The panel of experts should answer each statement with their degree of agreement, using a five-point, ordinal, Likert-type scale. The scale was rated as 1- ‘strongly disagree’, 2- ‘disagree’, 3- ‘neither agree nor disagree’, 4- ‘agree’ and 5- ‘strongly agree’. Additionally, panel members during rounds 1 and 2 had the opportunity to add comments to each statement in free-text boxes. The modified Delphi study ran between October 2019 and November 2019. Panelists answered via an online survey platform for each round (Welphi Platform).

The research assistance team assessed and presented the overall results from each round to all participants (groups’ responses and individual response) to facilitate comments and clarifications on the statements.

In 2nd and 3rd rounds, panel members contrasted their previous round personal opinion with other participants’ opinions. When they decided, participants were allowed to reassess their initial opinion on those statements where consensus was not reached. In the 2nd round, relevant comments from 1st round could originate statement rephrasing, or addition of new statements, which were individually evaluated by the scientific committee before inclusion in Delphi. After the 3rd round, the scientific committee met face-to-face and, subsequently had a face-to-face meeting with the panelists to discuss the final results and gather more in-depth opinions.

Data analysisFor the purpose of the analysis, the answers given to categories ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’, or on the categories ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘disagree’ were aggregated into ‘positive consensus’ and ‘negative consensus’, respectively. As convergence indicators, the percentage variation of the concordance ratio between rounds was used.

Consensus threshold (cut-off concordance) was established as a percentage of agreement among the participants for each individual item equal or greater to 90% (≥90%) in the 1st round; and equal or greater to 85% (≥85%) in the 2nd and 3rd rounds. A statement that did not reach consensus on the 1st round was reconsidered in the following round and so on. After three rounds, the remaining statements were considered to have not reached consensus. The scores and the level of consensus achieved by panelists were used to analyze the group opinion for each item.23

ResultsOverall, 46 of all 48 invited panelists completed the three rounds of the Delphi consensus (95.8% compliance). No new items were proposed during the exercise. Three items (two from topic 1 and one from topic 3) had their text reformulated after the 1st round by the scientific committee to improve interpretability, as suggested by the panelists.

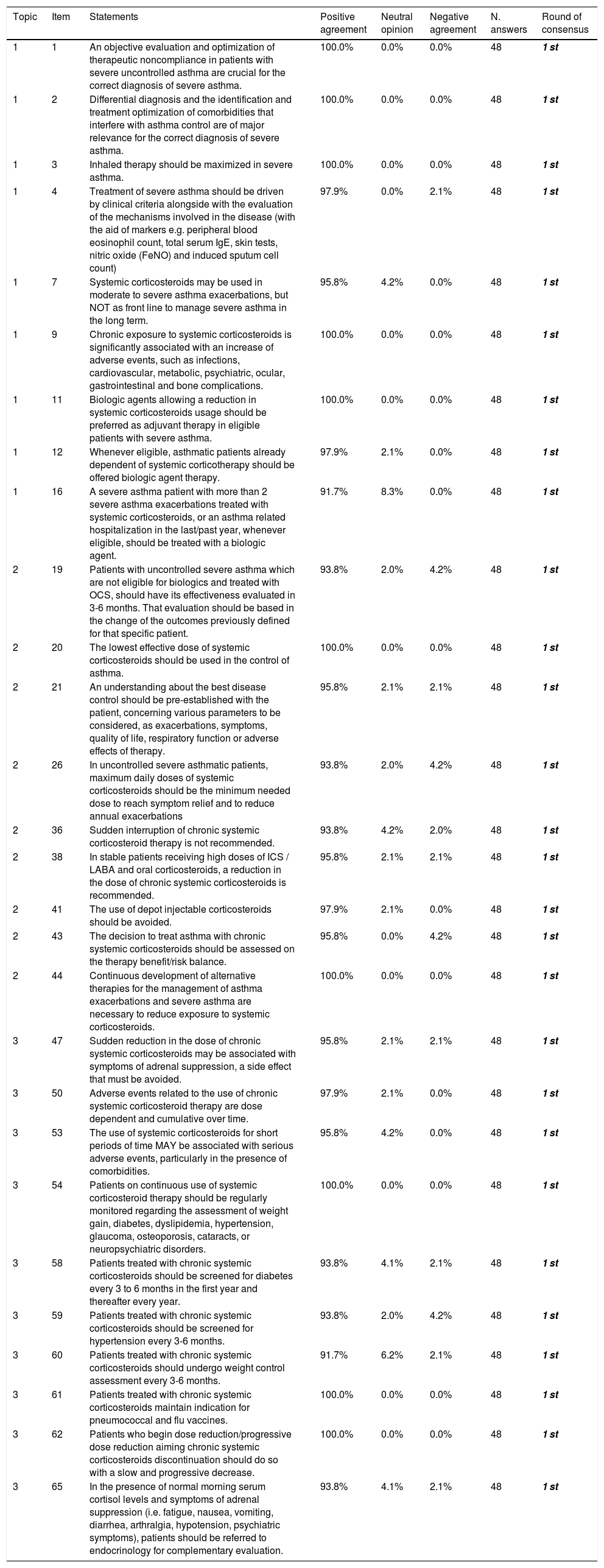

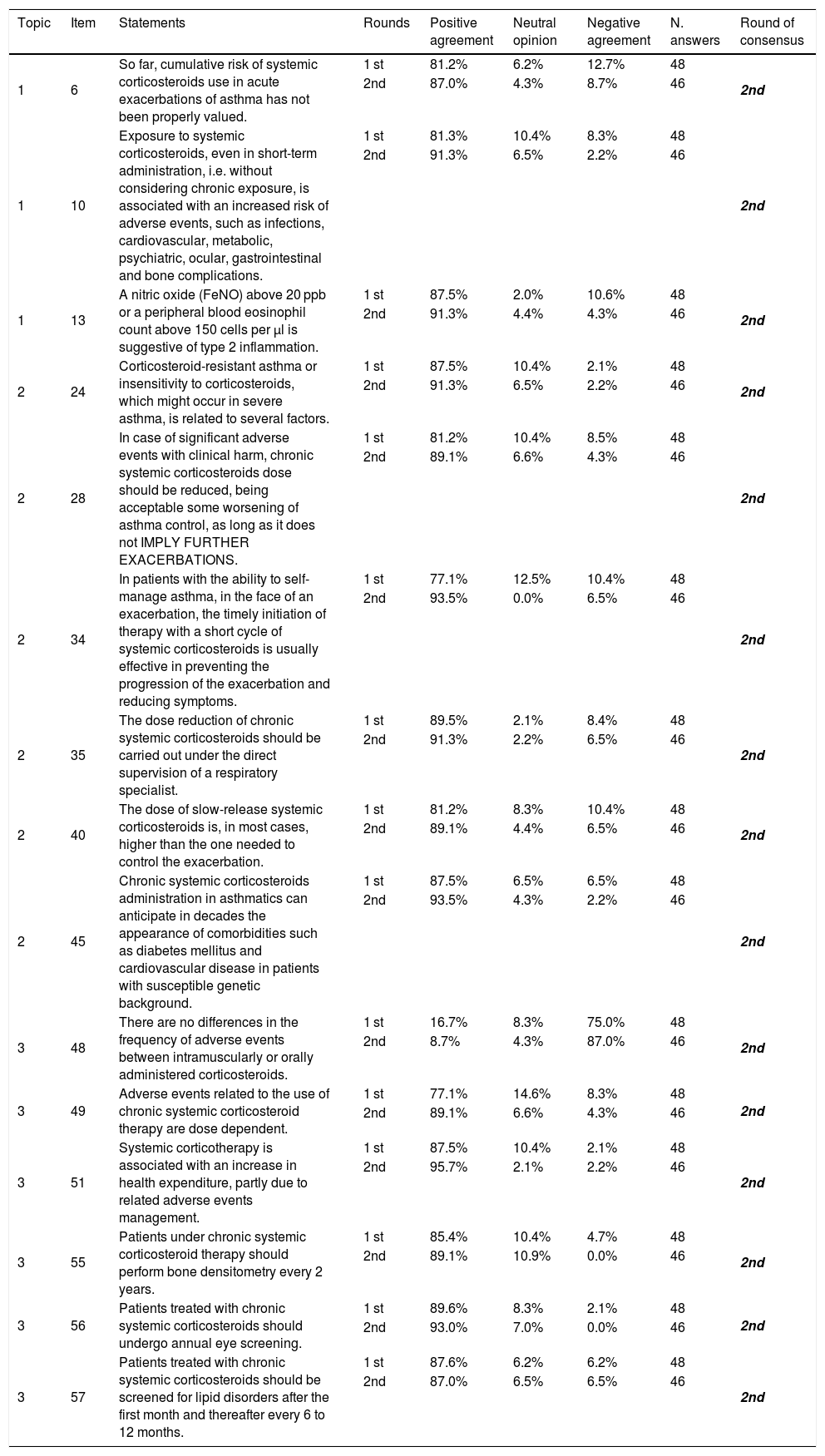

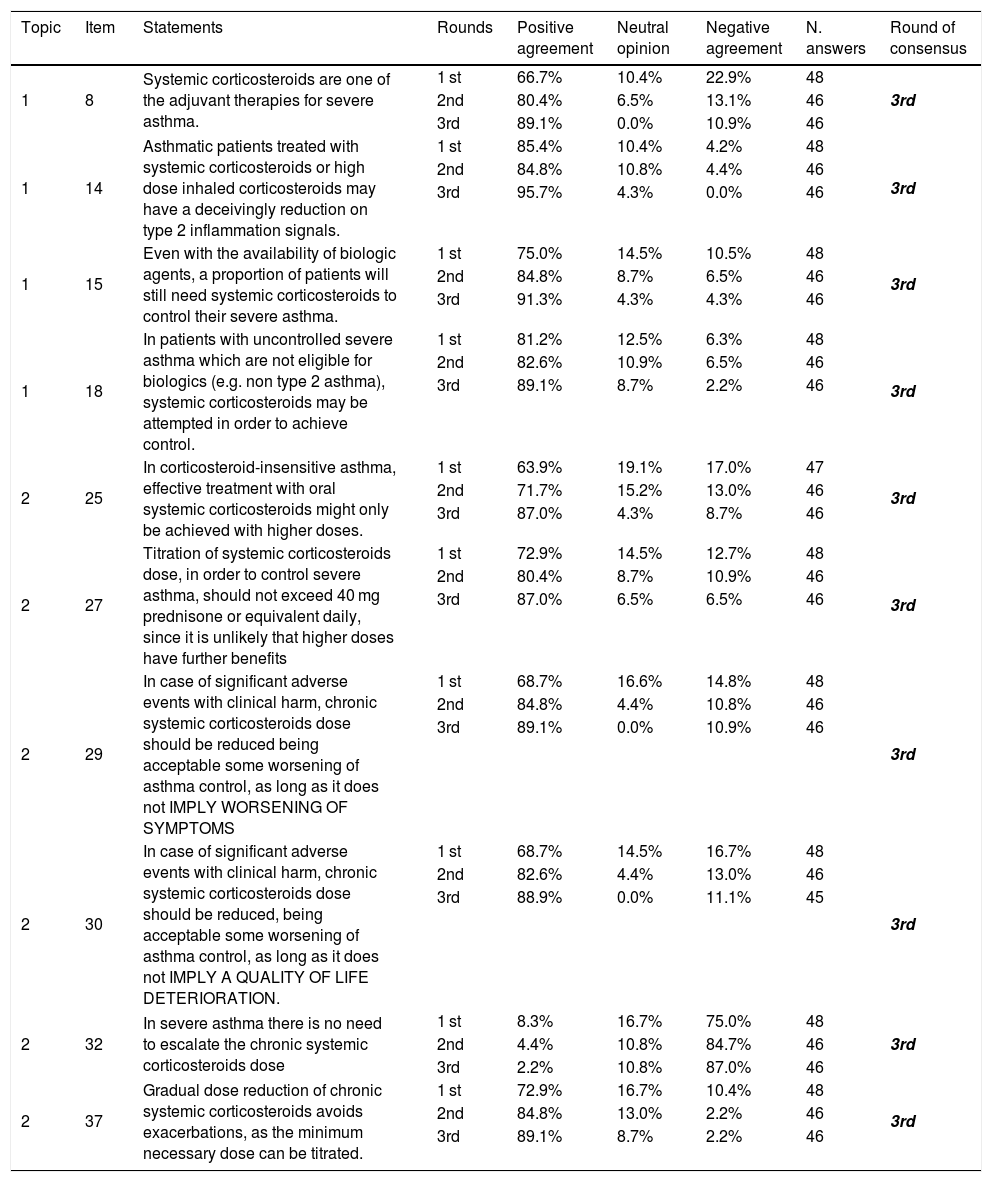

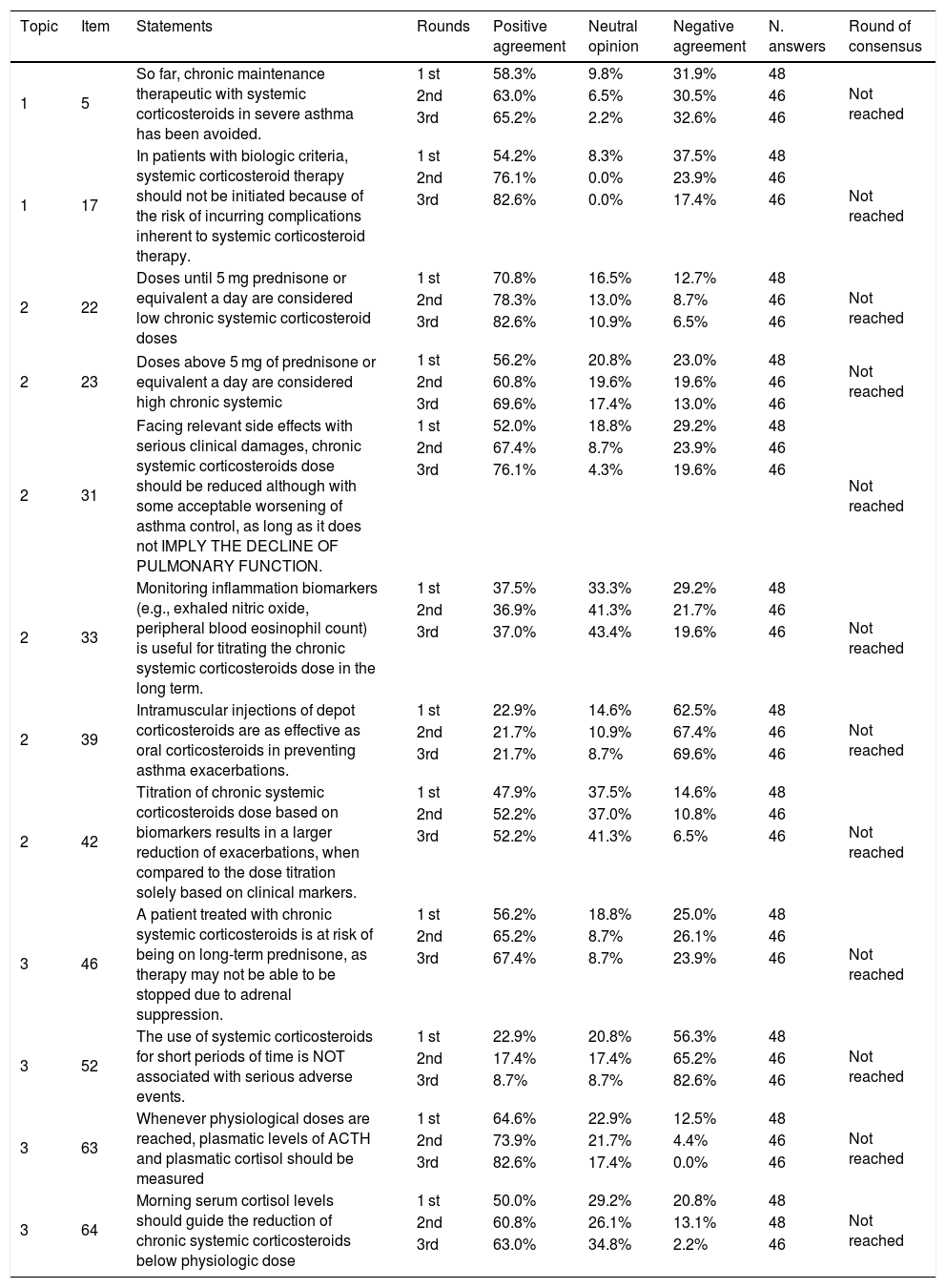

Fig. 1 shows the flowchart of the Delphi exercise. In the 1st round, consensus was reached on 28 of the 65 items (43.1%), all of them due agreement (see Table 1). Ten statements had a concordance equal to 100% (statements 1, 2, 3, 9, 11, 20, 44, 54, 61, 62). Thirty-seven remaining items were iterated in the 2nd round, where 15 items (40.5%) reached consensus (14 in agreement and one in disagreement) (see Table 2). During the 3rd round, for the 22 remaining statements, 10 (45.5%) obtained consensus (nine in agreement and one in disagreement) (see Table 3). By the end of the Delphi exercise, twelve statements had not achieved consensus (18.5%) (items 5, 17, 22, 23, 31, 33, 39, 42, 46, 52, 63, 64) (see Table 4). See supplemental material (Tables S1) for complete analysis in the original language (Portuguese).

Results of the Delphi exercise: items reaching consensus in the 1st round.

| Topic | Item | Statements | Positive agreement | Neutral opinion | Negative agreement | N. answers | Round of consensus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | An objective evaluation and optimization of therapeutic noncompliance in patients with severe uncontrolled asthma are crucial for the correct diagnosis of severe asthma. | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 1 | 2 | Differential diagnosis and the identification and treatment optimization of comorbidities that interfere with asthma control are of major relevance for the correct diagnosis of severe asthma. | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 1 | 3 | Inhaled therapy should be maximized in severe asthma. | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 1 | 4 | Treatment of severe asthma should be driven by clinical criteria alongside with the evaluation of the mechanisms involved in the disease (with the aid of markers e.g. peripheral blood eosinophil count, total serum IgE, skin tests, nitric oxide (FeNO) and induced sputum cell count) | 97.9% | 0.0% | 2.1% | 48 | 1 st |

| 1 | 7 | Systemic corticosteroids may be used in moderate to severe asthma exacerbations, but NOT as front line to manage severe asthma in the long term. | 95.8% | 4.2% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 1 | 9 | Chronic exposure to systemic corticosteroids is significantly associated with an increase of adverse events, such as infections, cardiovascular, metabolic, psychiatric, ocular, gastrointestinal and bone complications. | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 1 | 11 | Biologic agents allowing a reduction in systemic corticosteroids usage should be preferred as adjuvant therapy in eligible patients with severe asthma. | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 1 | 12 | Whenever eligible, asthmatic patients already dependent of systemic corticotherapy should be offered biologic agent therapy. | 97.9% | 2.1% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 1 | 16 | A severe asthma patient with more than 2 severe asthma exacerbations treated with systemic corticosteroids, or an asthma related hospitalization in the last/past year, whenever eligible, should be treated with a biologic agent. | 91.7% | 8.3% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 2 | 19 | Patients with uncontrolled severe asthma which are not eligible for biologics and treated with OCS, should have its effectiveness evaluated in 3-6 months. That evaluation should be based in the change of the outcomes previously defined for that specific patient. | 93.8% | 2.0% | 4.2% | 48 | 1 st |

| 2 | 20 | The lowest effective dose of systemic corticosteroids should be used in the control of asthma. | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 2 | 21 | An understanding about the best disease control should be pre-established with the patient, concerning various parameters to be considered, as exacerbations, symptoms, quality of life, respiratory function or adverse effects of therapy. | 95.8% | 2.1% | 2.1% | 48 | 1 st |

| 2 | 26 | In uncontrolled severe asthmatic patients, maximum daily doses of systemic corticosteroids should be the minimum needed dose to reach symptom relief and to reduce annual exacerbations | 93.8% | 2.0% | 4.2% | 48 | 1 st |

| 2 | 36 | Sudden interruption of chronic systemic corticosteroid therapy is not recommended. | 93.8% | 4.2% | 2.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 2 | 38 | In stable patients receiving high doses of ICS / LABA and oral corticosteroids, a reduction in the dose of chronic systemic corticosteroids is recommended. | 95.8% | 2.1% | 2.1% | 48 | 1 st |

| 2 | 41 | The use of depot injectable corticosteroids should be avoided. | 97.9% | 2.1% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 2 | 43 | The decision to treat asthma with chronic systemic corticosteroids should be assessed on the therapy benefit/risk balance. | 95.8% | 0.0% | 4.2% | 48 | 1 st |

| 2 | 44 | Continuous development of alternative therapies for the management of asthma exacerbations and severe asthma are necessary to reduce exposure to systemic corticosteroids. | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 3 | 47 | Sudden reduction in the dose of chronic systemic corticosteroids may be associated with symptoms of adrenal suppression, a side effect that must be avoided. | 95.8% | 2.1% | 2.1% | 48 | 1 st |

| 3 | 50 | Adverse events related to the use of chronic systemic corticosteroid therapy are dose dependent and cumulative over time. | 97.9% | 2.1% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 3 | 53 | The use of systemic corticosteroids for short periods of time MAY be associated with serious adverse events, particularly in the presence of comorbidities. | 95.8% | 4.2% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 3 | 54 | Patients on continuous use of systemic corticosteroid therapy should be regularly monitored regarding the assessment of weight gain, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, glaucoma, osteoporosis, cataracts, or neuropsychiatric disorders. | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 3 | 58 | Patients treated with chronic systemic corticosteroids should be screened for diabetes every 3 to 6 months in the first year and thereafter every year. | 93.8% | 4.1% | 2.1% | 48 | 1 st |

| 3 | 59 | Patients treated with chronic systemic corticosteroids should be screened for hypertension every 3-6 months. | 93.8% | 2.0% | 4.2% | 48 | 1 st |

| 3 | 60 | Patients treated with chronic systemic corticosteroids should undergo weight control assessment every 3-6 months. | 91.7% | 6.2% | 2.1% | 48 | 1 st |

| 3 | 61 | Patients treated with chronic systemic corticosteroids maintain indication for pneumococcal and flu vaccines. | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 3 | 62 | Patients who begin dose reduction/progressive dose reduction aiming chronic systemic corticosteroids discontinuation should do so with a slow and progressive decrease. | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 48 | 1 st |

| 3 | 65 | In the presence of normal morning serum cortisol levels and symptoms of adrenal suppression (i.e. fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, arthralgia, hypotension, psychiatric symptoms), patients should be referred to endocrinology for complementary evaluation. | 93.8% | 4.1% | 2.1% | 48 | 1 st |

Results of the Delphi exercise: items reaching consensus in the 2nd round.

| Topic | Item | Statements | Rounds | Positive agreement | Neutral opinion | Negative agreement | N. answers | Round of consensus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | So far, cumulative risk of systemic corticosteroids use in acute exacerbations of asthma has not been properly valued. | 1 st | 81.2% | 6.2% | 12.7% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 87.0% | 4.3% | 8.7% | 46 | ||||

| 1 | 10 | Exposure to systemic corticosteroids, even in short-term administration, i.e. without considering chronic exposure, is associated with an increased risk of adverse events, such as infections, cardiovascular, metabolic, psychiatric, ocular, gastrointestinal and bone complications. | 1 st | 81.3% | 10.4% | 8.3% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 91.3% | 6.5% | 2.2% | 46 | ||||

| 1 | 13 | A nitric oxide (FeNO) above 20 ppb or a peripheral blood eosinophil count above 150 cells per μl is suggestive of type 2 inflammation. | 1 st | 87.5% | 2.0% | 10.6% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 91.3% | 4.4% | 4.3% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 24 | Corticosteroid-resistant asthma or insensitivity to corticosteroids, which might occur in severe asthma, is related to several factors. | 1 st | 87.5% | 10.4% | 2.1% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 91.3% | 6.5% | 2.2% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 28 | In case of significant adverse events with clinical harm, chronic systemic corticosteroids dose should be reduced, being acceptable some worsening of asthma control, as long as it does not IMPLY FURTHER EXACERBATIONS. | 1 st | 81.2% | 10.4% | 8.5% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 89.1% | 6.6% | 4.3% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 34 | In patients with the ability to self-manage asthma, in the face of an exacerbation, the timely initiation of therapy with a short cycle of systemic corticosteroids is usually effective in preventing the progression of the exacerbation and reducing symptoms. | 1 st | 77.1% | 12.5% | 10.4% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 93.5% | 0.0% | 6.5% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 35 | The dose reduction of chronic systemic corticosteroids should be carried out under the direct supervision of a respiratory specialist. | 1 st | 89.5% | 2.1% | 8.4% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 91.3% | 2.2% | 6.5% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 40 | The dose of slow-release systemic corticosteroids is, in most cases, higher than the one needed to control the exacerbation. | 1 st | 81.2% | 8.3% | 10.4% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 89.1% | 4.4% | 6.5% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 45 | Chronic systemic corticosteroids administration in asthmatics can anticipate in decades the appearance of comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease in patients with susceptible genetic background. | 1 st | 87.5% | 6.5% | 6.5% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 93.5% | 4.3% | 2.2% | 46 | ||||

| 3 | 48 | There are no differences in the frequency of adverse events between intramuscularly or orally administered corticosteroids. | 1 st | 16.7% | 8.3% | 75.0% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 8.7% | 4.3% | 87.0% | 46 | ||||

| 3 | 49 | Adverse events related to the use of chronic systemic corticosteroid therapy are dose dependent. | 1 st | 77.1% | 14.6% | 8.3% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 89.1% | 6.6% | 4.3% | 46 | ||||

| 3 | 51 | Systemic corticotherapy is associated with an increase in health expenditure, partly due to related adverse events management. | 1 st | 87.5% | 10.4% | 2.1% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 95.7% | 2.1% | 2.2% | 46 | ||||

| 3 | 55 | Patients under chronic systemic corticosteroid therapy should perform bone densitometry every 2 years. | 1 st | 85.4% | 10.4% | 4.7% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 89.1% | 10.9% | 0.0% | 46 | ||||

| 3 | 56 | Patients treated with chronic systemic corticosteroids should undergo annual eye screening. | 1 st | 89.6% | 8.3% | 2.1% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 93.0% | 7.0% | 0.0% | 46 | ||||

| 3 | 57 | Patients treated with chronic systemic corticosteroids should be screened for lipid disorders after the first month and thereafter every 6 to 12 months. | 1 st | 87.6% | 6.2% | 6.2% | 48 | 2nd |

| 2nd | 87.0% | 6.5% | 6.5% | 46 |

Results of the Delphi exercise: items reaching consensus in the 3rd round.

| Topic | Item | Statements | Rounds | Positive agreement | Neutral opinion | Negative agreement | N. answers | Round of consensus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | Systemic corticosteroids are one of the adjuvant therapies for severe asthma. | 1 st | 66.7% | 10.4% | 22.9% | 48 | 3rd |

| 2nd | 80.4% | 6.5% | 13.1% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 89.1% | 0.0% | 10.9% | 46 | ||||

| 1 | 14 | Asthmatic patients treated with systemic corticosteroids or high dose inhaled corticosteroids may have a deceivingly reduction on type 2 inflammation signals. | 1 st | 85.4% | 10.4% | 4.2% | 48 | 3rd |

| 2nd | 84.8% | 10.8% | 4.4% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 95.7% | 4.3% | 0.0% | 46 | ||||

| 1 | 15 | Even with the availability of biologic agents, a proportion of patients will still need systemic corticosteroids to control their severe asthma. | 1 st | 75.0% | 14.5% | 10.5% | 48 | 3rd |

| 2nd | 84.8% | 8.7% | 6.5% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 91.3% | 4.3% | 4.3% | 46 | ||||

| 1 | 18 | In patients with uncontrolled severe asthma which are not eligible for biologics (e.g. non type 2 asthma), systemic corticosteroids may be attempted in order to achieve control. | 1 st | 81.2% | 12.5% | 6.3% | 48 | 3rd |

| 2nd | 82.6% | 10.9% | 6.5% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 89.1% | 8.7% | 2.2% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 25 | In corticosteroid-insensitive asthma, effective treatment with oral systemic corticosteroids might only be achieved with higher doses. | 1 st | 63.9% | 19.1% | 17.0% | 47 | 3rd |

| 2nd | 71.7% | 15.2% | 13.0% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 87.0% | 4.3% | 8.7% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 27 | Titration of systemic corticosteroids dose, in order to control severe asthma, should not exceed 40 mg prednisone or equivalent daily, since it is unlikely that higher doses have further benefits | 1 st | 72.9% | 14.5% | 12.7% | 48 | 3rd |

| 2nd | 80.4% | 8.7% | 10.9% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 87.0% | 6.5% | 6.5% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 29 | In case of significant adverse events with clinical harm, chronic systemic corticosteroids dose should be reduced being acceptable some worsening of asthma control, as long as it does not IMPLY WORSENING OF SYMPTOMS | 1 st | 68.7% | 16.6% | 14.8% | 48 | 3rd |

| 2nd | 84.8% | 4.4% | 10.8% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 89.1% | 0.0% | 10.9% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 30 | In case of significant adverse events with clinical harm, chronic systemic corticosteroids dose should be reduced, being acceptable some worsening of asthma control, as long as it does not IMPLY A QUALITY OF LIFE DETERIORATION. | 1 st | 68.7% | 14.5% | 16.7% | 48 | 3rd |

| 2nd | 82.6% | 4.4% | 13.0% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 88.9% | 0.0% | 11.1% | 45 | ||||

| 2 | 32 | In severe asthma there is no need to escalate the chronic systemic corticosteroids dose | 1 st | 8.3% | 16.7% | 75.0% | 48 | 3rd |

| 2nd | 4.4% | 10.8% | 84.7% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 2.2% | 10.8% | 87.0% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 37 | Gradual dose reduction of chronic systemic corticosteroids avoids exacerbations, as the minimum necessary dose can be titrated. | 1 st | 72.9% | 16.7% | 10.4% | 48 | 3rd |

| 2nd | 84.8% | 13.0% | 2.2% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 89.1% | 8.7% | 2.2% | 46 |

Results of the Delphi exercise: items without consensus.

| Topic | Item | Statements | Rounds | Positive agreement | Neutral opinion | Negative agreement | N. answers | Round of consensus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | So far, chronic maintenance therapeutic with systemic corticosteroids in severe asthma has been avoided. | 1 st | 58.3% | 9.8% | 31.9% | 48 | Not reached |

| 2nd | 63.0% | 6.5% | 30.5% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 65.2% | 2.2% | 32.6% | 46 | ||||

| 1 | 17 | In patients with biologic criteria, systemic corticosteroid therapy should not be initiated because of the risk of incurring complications inherent to systemic corticosteroid therapy. | 1 st | 54.2% | 8.3% | 37.5% | 48 | Not reached |

| 2nd | 76.1% | 0.0% | 23.9% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 82.6% | 0.0% | 17.4% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 22 | Doses until 5 mg prednisone or equivalent a day are considered low chronic systemic corticosteroid doses | 1 st | 70.8% | 16.5% | 12.7% | 48 | Not reached |

| 2nd | 78.3% | 13.0% | 8.7% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 82.6% | 10.9% | 6.5% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 23 | Doses above 5 mg of prednisone or equivalent a day are considered high chronic systemic | 1 st | 56.2% | 20.8% | 23.0% | 48 | Not reached |

| 2nd | 60.8% | 19.6% | 19.6% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 69.6% | 17.4% | 13.0% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 31 | Facing relevant side effects with serious clinical damages, chronic systemic corticosteroids dose should be reduced although with some acceptable worsening of asthma control, as long as it does not IMPLY THE DECLINE OF PULMONARY FUNCTION. | 1 st | 52.0% | 18.8% | 29.2% | 48 | Not reached |

| 2nd | 67.4% | 8.7% | 23.9% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 76.1% | 4.3% | 19.6% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 33 | Monitoring inflammation biomarkers (e.g., exhaled nitric oxide, peripheral blood eosinophil count) is useful for titrating the chronic systemic corticosteroids dose in the long term. | 1 st | 37.5% | 33.3% | 29.2% | 48 | Not reached |

| 2nd | 36.9% | 41.3% | 21.7% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 37.0% | 43.4% | 19.6% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 39 | Intramuscular injections of depot corticosteroids are as effective as oral corticosteroids in preventing asthma exacerbations. | 1 st | 22.9% | 14.6% | 62.5% | 48 | Not reached |

| 2nd | 21.7% | 10.9% | 67.4% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 21.7% | 8.7% | 69.6% | 46 | ||||

| 2 | 42 | Titration of chronic systemic corticosteroids dose based on biomarkers results in a larger reduction of exacerbations, when compared to the dose titration solely based on clinical markers. | 1 st | 47.9% | 37.5% | 14.6% | 48 | Not reached |

| 2nd | 52.2% | 37.0% | 10.8% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 52.2% | 41.3% | 6.5% | 46 | ||||

| 3 | 46 | A patient treated with chronic systemic corticosteroids is at risk of being on long-term prednisone, as therapy may not be able to be stopped due to adrenal suppression. | 1 st | 56.2% | 18.8% | 25.0% | 48 | Not reached |

| 2nd | 65.2% | 8.7% | 26.1% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 67.4% | 8.7% | 23.9% | 46 | ||||

| 3 | 52 | The use of systemic corticosteroids for short periods of time is NOT associated with serious adverse events. | 1 st | 22.9% | 20.8% | 56.3% | 48 | Not reached |

| 2nd | 17.4% | 17.4% | 65.2% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 8.7% | 8.7% | 82.6% | 46 | ||||

| 3 | 63 | Whenever physiological doses are reached, plasmatic levels of ACTH and plasmatic cortisol should be measured | 1 st | 64.6% | 22.9% | 12.5% | 48 | Not reached |

| 2nd | 73.9% | 21.7% | 4.4% | 46 | ||||

| 3rd | 82.6% | 17.4% | 0.0% | 46 | ||||

| 3 | 64 | Morning serum cortisol levels should guide the reduction of chronic systemic corticosteroids below physiologic dose | 1 st | 50.0% | 29.2% | 20.8% | 48 | Not reached |

| 2nd | 60.8% | 26.1% | 13.1% | 48 | ||||

| 3rd | 63.0% | 34.8% | 2.2% | 46 |

This topic aggregated 19 statements. During 1st round, n = 10 statements (52.6%) obtained positive consensus (categories ‘strongly agree’ or ‘agree’) (see Table 1). The remaining nine items did not reach agreement and, thus, were launched again in the 2nd round, where n = 3 (33.3%) obtained positive consensus (Table 2). In the last round, n = 4 out of the six remaining items (66.7%) reached consensus; two items did not reach consensus (10.5%) (Tables 3 and 4).

Topic 2: therapeutic schemes of systemic corticotherapy in crisis and maintenanceThis topic gathered 26 items, of which n = 8 (30.7%) obtained positive consensus in the 1st round (Table 1). The remaining statements were re-evaluated in the 2nd round, where n = 6 (33.3%) were positively consensualized (Table 2). The evaluation of the twelve items in 3rd round, resulted in consensus for n = 6 of them (50.0%), of which one obtained negative agreement (Table 3). Six other statements did not reach consensus in this topic (Table 4).

Topic 3: asthma safety and monitoringThis last topic comprised 20 statements. During 1st round, half of the items (n = 10) obtained positive consensus (Table 1), while the others followed to the next round. In the 2nd round, n = 6 were consensualized (60.0%) (Table 2), one of them with negative agreement. In the final round, none of the remaining four items (20.0%) reached consensus (Tables 3 and 4).

Some variations in the responses between rounds were observed. The median variation in agreement rates between 1st and 2nd rounds was 7.4% [IQR 3.7, 10.1], while between second and third rounds was 5.3% [IQR 2.2, 8.1]. Median variation in disagreement rates between the 1st and 2nd rounds was -3.7% [IQR -4.2, 0.1]; and between 2nd and 3rd rounds was -2.2% [IQR -4.4, -0.5]). Statements n. 17 (topic 1) and 34 (topic 2) presented the highest changes in agreement rates, expressed in percentage points (pp): 21.9 pp and 16.4 pp, respectively, between 1st and 2nd rounds. Between 2nd and 3rd rounds, statements 14 (topic 1) and 25 (topic 2) were those with highest variation (10.9 pp and 15.2 pp respectively). Statements n. 17 (topic 1) and 52 (topic 3) showed more variation in the disagreement rates: -13.6 pp (between 1st and 2nd rounds) and 17.4 pp (between 2nd and 3rd rounds), respectively (see supplemental material Table S2).

DiscussionWe were able to perform a nationwide and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus with the participation of experts from the different clinical specialties that daily treat adult patients with severe asthma in Portugal. The high level of compliance among panelists with this exercise (over 95% in all rounds) may reveal the perception of relevance of the topic for clinical practice.

The Delphi technique has the advantage of avoiding the dominant personality effect by using anonymous responses, and allows for the re-evaluation of panelists opinions in the light of group answers, without losing the gains from face-to-face discussions.24–26 Studies also stress the added value of comments along with personal interaction as a way of supporting the change on the level of agreement between rounds or to detail the reasons behind a lack of consensus.27,28

Almost half of the statements enrolled in this Delphi questionnaire obtained positive consensus by the end of round one; ten of them with a concordance equal 100%. By the end of the exercise, 12 statements had not reached consensus.

The lack of consensus in statement 5 “So far, chronic maintenance therapeutic with systemic corticosteroids in severe asthma has been avoided” may be due to lack of clarity of the text, leading to misinterpretation. Nevertheless, almost two-thirds of the panelists considered that there is no overuse of OCS in the maintenance therapeutics of severe asthma, which is far from the reality in our country,29 and therefore should be addressed in future educational actions. On the other hand, there was a consensus (87% of positive agreement) that further actions for the assessment of the cumulative risk of OCS use in acute asthma exacerbations are needed (statement 6 “So far, cumulative risk of systemic corticosteroids use in acute exacerbations of asthma has not been properly valued”).

For some statements, such as item 9 (“Chronic exposure to systemic corticosteroids is significantly associated with an increase of adverse events, such as infections, cardiovascular, metabolic, psychiatric, ocular, gastrointestinal and bone complications”) the full agreement in the 1st round was expected given the generic non-specific text. Nevertheless, statement 10 (“Exposure to systemic corticosteroids, even in short-term administration, i.e. without considering chronic exposure, is associated with an increased risk of adverse events, such as infections, cardiovascular, metabolic, psychiatric, ocular, gastrointestinal and bone complications”) only achieved consensus in the 2nd round. We might speculate that awareness of short-term OCS side-effects is lower but also, we should recognize that the statement did not quantify the increase in the number of adverse events nor define the meaning of short-term administration.

The positive consensus (91.3%) obtained for statement 15 in the last round (“Even with the availability of biologic agents, a proportion of patients will still need systemic corticosteroids to control their severe asthma”) demonstrated the ongoing debate on the substitution of OCS by other therapies. During the face-to-face meeting, the committee highlighted that even with the availability of new biologic agents, physicians may still consider the use of OCS for severe asthma. Indeed, an important percentage of severe asthma patients are not eligible for the already available biological agents and so, probably given the clinical experience with OCS in type 2 asthma, these therapies might still have a role.20,30 However, the positive consensus (91.7%) achieved for the statement 16 at the 1st round (“A severe asthma patient with more than 2 severe asthma exacerbations treated with systemic corticosteroids, or an asthma related hospitalization in the last/past year, whenever eligible, should be treated with a biologic agent”) demonstrated a favorable perception for using biologic agents. This emphasizes an especially important message for all physicians who face severe asthma patients (both in acute and chronic settings) that must increase their awareness for the availability of these novel therapies, reinforcing the need for a timely referral.

Consensus was not reached for statement 17: “In patients with biologic criteria, systemic corticosteroid therapy should not be initiated because of the risk of incurring complications inherent to systemic corticosteroid therapy”. This may have occurred given the existing delays for the approval of use of biologic agents in our country, which contributes to increasing the number of untreated patients who need to initiate OCS. The discussion with the experts revealed that OCS should usually be avoided before biologics, but when justified, they can be initiated at a minimum effective dosage for a short period of time. This means, biologic agents are now viewed as the first line of treatment for severe asthma, and OCS should be withdrawn as soon as possible once a biologic is initiated.

Patients that do not respond to treatment with biologics may also be unresponsive to OCS,31,32 especially because there are clear unmet needs requiring novel therapeutic approaches for non-type 2 asthma.19,20 This was highlighted by both statements 18 (“In patients with uncontrolled severe asthma which are not eligible for biologics (e.g. non type 2 asthma), systemic corticosteroids may be attempted in order to achieve control”) and 19 (“Patients with uncontrolled severe asthma which are not eligible for biologics and treated with OCS, should have its effectiveness evaluated in 3−6 months. That evaluation should be based in the change of the outcomes previously defined for that specific patient”). In this context, treatment with OCS still appears to be an important alternative for asthmatic patients, but periodic re-evaluation and tailored treatment towards patients’ needs are paramount to demonstrate the added value of this approach. If the added value is not reached, therapeutic strategies must be reconsidered. Asthma control encompasses objective clinical outcomes (e.g. pulmonary function and exacerbations), but also patient-reported outcomes (PROs), such as asthma symptoms, activity levels, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and patient satisfaction. PROs are important complementary measures of the patient's health care experience which should be considered when selecting treatment, because they supplement physiologic and clinical assessments of asthma and may influence compliance with therapy.33,34

The high positive agreement (95.8%) for statements 21 in the 1st round (“An understanding about the best disease control should be pre-established with the patient, concerning various parameters to be considered, as exacerbations, symptoms, quality of life, respiratory function or adverse effects of therapy”), together with the lack of consensus for statement 31 (“Facing relevant side effects with serious clinical damages, chronic systemic corticosteroids dose should be reduced although with some acceptable worsening of asthma control, as long as it does not IMPLY THE DECLINE OF PULMONARY FUNCTION”) may reveal that some degree of lung function deterioration may be more acceptable compared to outcomes such as worsening of symptoms or quality of life (HRQoL).

The lack of consensus in statements 22 and 23 (“Doses until 5 mg prednisone or equivalent a day are considered low chronic systemic corticosteroid doses” and “Doses above 5 mg of prednisone or equivalent a day are considered high chronic systemic”, respectively), may have occurred given the differences in the definition of ‘low dose’. Although a daily dose of 5 mg of prednisone or equivalent is usually assumed a low dose,4,5 further evidence on these thresholds may be necessary.

Statements 25 (“In corticosteroid-insensitive asthma, effective treatment with oral systemic corticosteroids might only be achieved with higher doses”) and 27 (“Titration of systemic corticosteroids dose, in order to control severe asthma, should not exceed 40 mg prednisone or equivalent daily, since it is unlikely to have further benefits with higher dose”), both of them with positive consensus in the 3rd round (87.0%), conceptualize the OCS plateau effect for anti-asthmatic efficacy. However, higher doses than 40 mg prednisone daily, or equivalent, should be avoided because there is an increased risk of adverse events without any evidence of added benefits.4,5,35

The lack of consensus in statement 39 “Intramuscular injections of depot corticosteroids are as effective as oral corticosteroids in preventing asthma exacerbations.” should be interpreted alongside statements 40 (“The dose of slow-release systemic corticosteroids is, in most cases, higher than the one needed to control the exacerbation”) and 41 (“The use of slow-release injectable corticosteroids should be avoided”) which obtained positive agreement in the 2nd and 1st rounds, respectively. These results indicate, as perceived in the face-to-face panel meeting, that item 39 should clearly state ‘in the treatment’ instead of ‘in prevention’. Additionally, long acting OCS should be avoided as stated in the rule: lowest dose, shortest treatment duration. Studies highlight the relevance of the cumulative steroid dose.36

The discussion of inflammation monitoring in asthma (statement 33 - “Monitoring inflammation biomarkers (e.g., exhaled nitric oxide, peripheral blood eosinophil count) is useful for titrating the chronic systemic corticosteroids dose in the long term”) further demonstrates a lack of consensus, probably due to access constraints to these evaluation methods rather than the lack of perception of relevance of the topic by the experts. Still, as shown by the debate from statement 42 (“Titration of chronic systemic corticosteroids dose based on biomarkers results in a larger reduction of exacerbations, when compared to the dose titration solely based on clinical markers”) the literature is ambiguous on the role of inflammation monitoring.5,37,38 On the other hand, monitoring patient comorbidities secondary to OCS side effects was rated as imperative by the experts with 100% positive consensus in the 1st round (statement 54 “Patients on continuous use of systemic corticosteroid therapy should be regularly monitored regarding the assessment of weight gain, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, glaucoma, osteoporosis, cataracts or neuropsychiatric disorders”), revealing the need for standardized clinical protocols of data collection and evaluation.

The absence of consensus in statement 46 (“A patient treated with chronic systemic corticosteroids is at risk of being on long-term prednisone, as therapy may not be able to be stopped due to adrenal suppression”) may be due to different reasons. OCS withdrawal is sometimes associated with adrenal suppression and some studies find that roughly 20% of patients develop adrenal suppression.15,30,38 Nevertheless, as no protocols to routinely evaluate these cases exist, this might correspond to an underestimate percentage. Keeping in mind the lack of guidance not only on OCS use in asthma context but also on how to monitor therapies side effects and withdrawals, it is important to develop protocols for daily practice.

The different interpretations of the concept of ‘physiological dose’ as well as the evaluation methods may justify the lack of consensus for both statement 63 (“Whenever physiological doses are reached, plasmatic levels of ACTH and plasmatic cortisol should be measured”) and statement 64 (“Morning serum cortisol levels should guide the reduction of chronic systemic corticosteroids bellow physiologic dose”). Based on the discussion with the experts, the steering committee stated that morning serum cortisol test should be carried out whenever possible because it is an easy, low-cost and accessible test which assists, among other things, the evaluation of adrenal insufficiency.

Despite evident strengths our study has some limitations. Our discussion is based on expert opinion rather than patient data; however, the Delphi technique is a widely used and accepted method for achieving convergence and is well recognized as a qualitative technique for data elicitation. The Delphi panel included only clinical specialists in asthma, selected as key opinion leaders, with the ability to describe clinical practice in Portugal, in secondary specialized care level. However, other healthcare professionals, in other healthcare settings, may have different opinions.

ConclusionsThe results of this study could be considered as a first step towards providing updated consensus of OCS use for asthma management in Portugal, and should be supplemented by additional studies, exploring treatment algorithms, therapy access, patient’s adherence, and costs.

FundingThis work was supported by AstraZeneca. The funding source had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and in the writing or submitting decision of the article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We'd like to thank all the experts who participated in the Delphi process related with the article (see the whole list in the Appendix B).