Men and women differ in their smoking behaviour: women smoke fewer cigarettes per day, their consumption is more related to sensory effects, mood and negative emotions, they start smoking later with a lower cumulative consumption and tend to use cigarettes with lower nicotine content, show lower dependency scores than men, become dependent earlier and have greater difficulty quitting smoking experiencing more severe nicotine withdrawal symtoms.1

We conducted an observational, multicenter study of consecutive patients who attended several smoking clinics to stop smoking between October 2014 and October 2015. We wanted to know if there were differences between men and women in terms of tobacco consumption. To investigate this we included qualitative variables (questionnaires to measure motivation to quit and nicotine dependence) and quantitative variables (age, tobacco consumption, number of years smoking, cumulative consumption, previous attempts to quit, number of attempts in the last year, and motivation to quit and nicotine dependence questionnaires). The statistical analysis was descriptive. A <0.05 value was considered as statistically significant. The study was authorized by the different ethics committees of the participating hospitals.

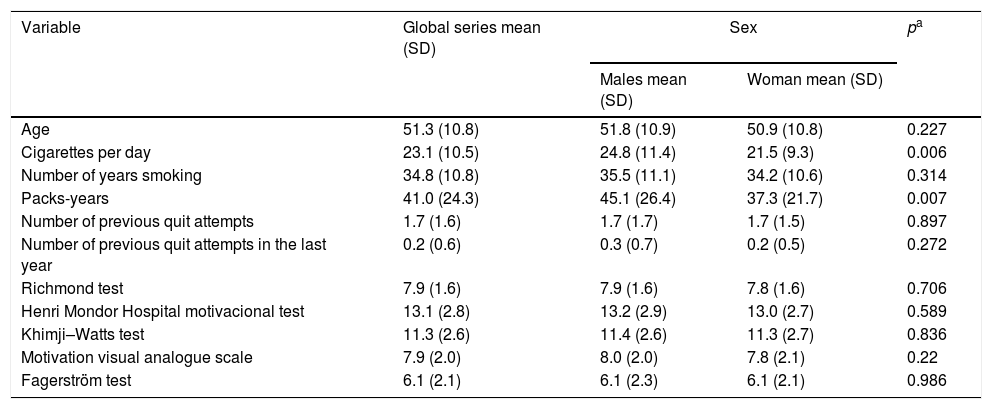

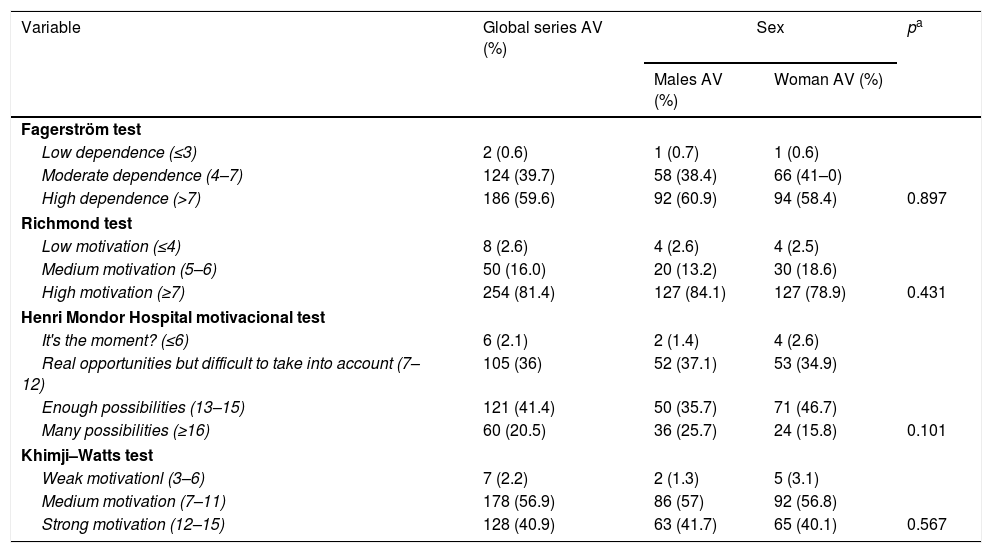

We included 314 patients [162 women, (51.59%)]. Table 1 shows the average values of the quantitative variables and Table 2 the percentage values of the qualitative variables. We found statistically significant differences between men and women in the amount of cigarettes consumption per day and in the “cumulative consumption of tobacco” variable. Men smoked on average 3.3 cigarettes/day more than women (95% CI: 0.9–5.6 cigarettes/day, p=0.006), and the cumulative consumption of men was higher than women by 7.8 pack-years (95% CI: 2.1–13.5 pack-years, p=0.007). We did not find any significant differences between sexes in the rest of the variables analyzed,

Mean values of the quantitative variables for the global series and by sex, and comparison between men and women.

| Variable | Global series mean (SD) | Sex | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males mean (SD) | Woman mean (SD) | |||

| Age | 51.3 (10.8) | 51.8 (10.9) | 50.9 (10.8) | 0.227 |

| Cigarettes per day | 23.1 (10.5) | 24.8 (11.4) | 21.5 (9.3) | 0.006 |

| Number of years smoking | 34.8 (10.8) | 35.5 (11.1) | 34.2 (10.6) | 0.314 |

| Packs-years | 41.0 (24.3) | 45.1 (26.4) | 37.3 (21.7) | 0.007 |

| Number of previous quit attempts | 1.7 (1.6) | 1.7 (1.7) | 1.7 (1.5) | 0.897 |

| Number of previous quit attempts in the last year | 0.2 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.272 |

| Richmond test | 7.9 (1.6) | 7.9 (1.6) | 7.8 (1.6) | 0.706 |

| Henri Mondor Hospital motivacional test | 13.1 (2.8) | 13.2 (2.9) | 13.0 (2.7) | 0.589 |

| Khimji–Watts test | 11.3 (2.6) | 11.4 (2.6) | 11.3 (2.7) | 0.836 |

| Motivation visual analogue scale | 7.9 (2.0) | 8.0 (2.0) | 7.8 (2.1) | 0.22 |

| Fagerström test | 6.1 (2.1) | 6.1 (2.3) | 6.1 (2.1) | 0.986 |

SD: standard deviation.

p: degree of significance of the comparison of means between men and women.

The t-Student test or the Welch test for the comparison of mean values, or, if a normal distribution was not reached, the U-Mann–Whitney test was used. The assumption of homogeneity of the variances was proven by the Levene test. An α<0.05 value was considered as statistically significant.

Frequency distribution of qualitative variables for the global series and by sex, and comparison between men and women.

| Variable | Global series AV (%) | Sex | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males AV (%) | Woman AV (%) | |||

| Fagerström test | ||||

| Low dependence (≤3) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Moderate dependence (4–7) | 124 (39.7) | 58 (38.4) | 66 (41–0) | |

| High dependence (>7) | 186 (59.6) | 92 (60.9) | 94 (58.4) | 0.897 |

| Richmond test | ||||

| Low motivation (≤4) | 8 (2.6) | 4 (2.6) | 4 (2.5) | |

| Medium motivation (5–6) | 50 (16.0) | 20 (13.2) | 30 (18.6) | |

| High motivation (≥7) | 254 (81.4) | 127 (84.1) | 127 (78.9) | 0.431 |

| Henri Mondor Hospital motivacional test | ||||

| It's the moment? (≤6) | 6 (2.1) | 2 (1.4) | 4 (2.6) | |

| Real opportunities but difficult to take into account (7–12) | 105 (36) | 52 (37.1) | 53 (34.9) | |

| Enough possibilities (13–15) | 121 (41.4) | 50 (35.7) | 71 (46.7) | |

| Many possibilities (≥16) | 60 (20.5) | 36 (25.7) | 24 (15.8) | 0.101 |

| Khimji–Watts test | ||||

| Weak motivationl (3–6) | 7 (2.2) | 2 (1.3) | 5 (3.1) | |

| Medium motivation (7–11) | 178 (56.9) | 86 (57) | 92 (56.8) | |

| Strong motivation (12–15) | 128 (40.9) | 63 (41.7) | 65 (40.1) | 0.567 |

In the boxes of the column “Global series” the absolute value is indicated and between () the percentage. In the columns “Males” and “Females” it is indicated in this order: absolute value; () indicates the percentage within the sex, that is, read the table by columns.

p: degree of significance of the comparison of means between men and women.

The t-Student test or the Welch test for the comparison of mean values, or, if a normal distribution was not reached, the U-Mann–Whitney test was used. The assumption of homogeneity of the variances was proven by the Levene test. An α<0.05 value was considered as statistically significant.

We did not find any differences between men and women in terms of the degree of nicotine dependence or motivation to stop smoking, which has already been written about by other authors.2 We are aware that although our sample included 314 smokers, it may not have sufficient statistical strength to identify differences between sexes, which is a possible limitation of our study. Other possible limitations would be that the findings were collected from smokers, who voluntarily attended smoking cessation clinics, and the survey was carried out in different scenarios and geographical locations which might not reflect what would happen if the tests had been administered to the general population. Another limitation could be related to the use of questionnaires in patients because results obtained are not always accurate. This variability could lead to different results.

Differences between men and women have been previously reported suggesting women are less likely to show nicotine dependence than men.1 The behaviour of woman who smoke is influenced to a greater extent by conditioning factors related to mood and negative emotions, while for men it is more related to pharmacological signals regulated by nicotine consumption. It is worth noting that women metabolize nicotine more quickly than men and have a higher prevalence to depression, which may be related to a greater addiction. In addition, women present a more severe and different withdrawal symptoms than men1 which makes it more difficult for them to quit smoking. Although women make the same number of attempts to quit smoking as men, they are less likely to maintain abstinence. All of the above suggests that although women's dependence on tobacco is lower, there may be other factors that make quitting more difficult.1 Komiyama et al.2 in a study intended to examine the interactions of factors related to tobacco consumption, found that men smoked more cigarettes per day, with a greater cumulative consumption of tobacco and had a longer time of tobacco consumption than women, but they did not find differences between men and women regarding nicotine dependence assessed by the Fagerström Nicotine Questionnaire. Women did show a higher tendency to depression and only here was a high dependency value correlated with a greater depression scale, findings that could reflect existing differences in response to psychological stress.

Gender differences have been demonstrated in terms of reinforcement and reward for nicotine, reflecting dissimilarities in dopaminergic neurotransmission regulation. It has been demonstrated that the availability as a binding potential of dopamine receptors (D2-type) is lower in the caudate nucleus and putamen of male smokers compared to non-smokers, however, this was not observed in women,3 who responded by releasing dopamine consistently in the ventral striatum and faster than men in the dorsal putamen.4 Okita et al.5 found gender differences in how dopamine receptors in the midbrain influence nicotine dependence, which may explain why women would benefit less from nicotine replacement therapy, because the release of dopamine would be limited by the high density in the middle brain of D2 dopamine receptors.

Curry et al.6 evaluated a model of both intrinsic motivation (related to health, self-control) and extrinsic motivation (immediate reinforcement and social influence) to stop smoking, and found that motivation in woman was related to immediate reinforcement which could explain their greater difficulty in quitting, because according to this model those smokers with high levels of intrinsic motivation would have better chances of stopping smoking than those with greater extrinsic motivation. The consumption of tobacco in women express higher levels of negative expectancy smoking reinforcement,7 which indicates that reduction in negative emotions could constitute an important motivational factor that governs the consumption of tobacco in women, so treatment for women should focus more on cognitive-behavioural techniques oriented towards coping with negative emotions without smoking.7

Understanding individual sex differences in smoking behaviour and nicotine dependence could increase knowledge and help in the development of more effective treatment regimens.

FundingThe project was funded by an unrestricted grant from The Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery 2013.

Conflicts of interestNo conflicts of interest.